A Place to Sit Alone and

Find One's Heart

Three Days of “Mumungwan” Practice at Gapsa Temple on Mt. Gyeryongsan

Text by. Son In-ho Photo by. Nam Yun-jung

“Mumungwan,” a Special Program Only Available at Gapsa Temple, From among the 158 Templestay Temples across Korea

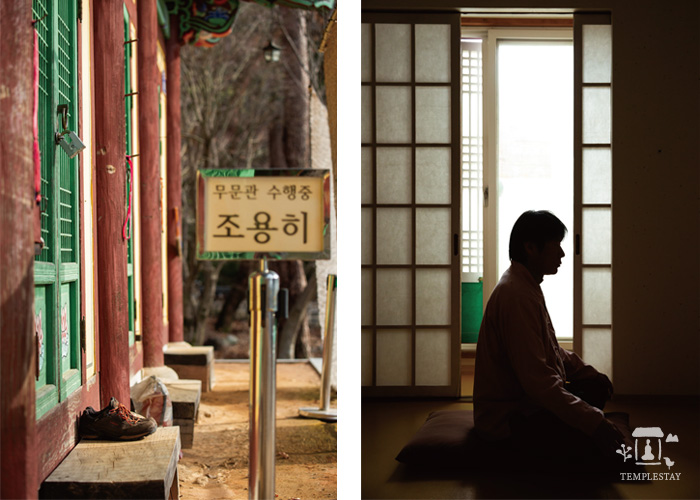

“Immerse yourself into practice, please!” and “click,” the sound of the door being locked from outside.

In this small room blocked by walls all around, will I be able to eventually leap up and soar like a bird?

In the foothills of Mt. Gyeryongsan, full of magical energy, sitting opposite a wall, staring at a paper with a dot on it, staying in my own space of the gateless gate, can I be awakened and say “Aha!” and laugh freely?

Before the flowers of spring began to bloom, I participated in the Mumungwan Templestay at Gapsa Temple in the foothills of Mt. Gyeryongsan. And now I sit and write this article beside a white and blue sea. This is the only thing clear to me here and now. What has happened so far? My mind feels like a tangle of threads with the ends extending inward, or perhaps gray and empty, as if my brain fluid has slowly leaked out. Meanwhile, the hands of the wall clock move in a circle, and time flows mercilessly in only one direction. Ah, I so much want the present to be that day... , I wish it were that early spring day when I practiced Mumungwan... .

A Temple with a Sad Medicine Buddha

Gapsa Temple is a place I have been to a few times recently. Whenever I walk the mountain path from Donghaksa Temple to Gapsa Temple, I feel like I am walking through a story. I used to sit for a long time next to Nammaetap Pagoda (lit. “Brother and Sister Pagoda”), a pagoda that struck me as being both kind and heartless at the same time. As I walked the mountain path that never seemed to end, time seemed to stop briefly each time I greeted and listened to each stone, patch of moss, and tree.

I felt like a small animal. Usually, when I go to Gapsa, the first thing I do is visit Yaksajeon (Hall of Medicine Buddha) to pray. Every time I see the sad, thin figure of the Stone Standing Medicine Buddha, I think it is expressing sorrow for not being able to cure all the illnesses of the world. I felt that way that day too.

Templestay temples across Korea operate various programs, but I was quite surprised to hear that lay Buddhists can also experience “Mumungwan” practice at Gapsa Temple. A documentary film I once saw about Mumungwan practice remains fresh in my memory. Five monks entered Mumungwan to practice devoutly for three years with the single intention of immersing themselves in undaunted self-cultivation.

The moment the door was finally locked from the outside, the Buddhists watching the scene burst into tears. It is said that after three years, a sparrow living near a school can sing the school's primer. The video recorded the entire process of those three years. One monk caused a stir by running out of his room to ask a question to the senior Seon master because he was stuck in investigating his hwadu. Another monk got sick from the extreme isolation of practice, and another monk's elderly mother passed away while he was in isolation.

Gapsa's Mumungwan Templestay for lay Buddhists usually lasts 2 nights and 3 days, but can last up to 7 nights 8 days. I have heard that even among ordained practitioners, only those with advanced levels of practice can endure Mumungwan practice. Mumungwan is the extreme Seon practice—normally only for ordained practitioners—where one volunteers to be locked alone in a room for a set period of time; it can last three months or at most three years.

All external stimuli are blocked and one faces one's inner self head-on. I am amazed and grateful for the determination and insight of Gapsa's abbot and the program planner who allowed lay Buddhist Templestay participants to experience this unique practice.

Where Did the Cow Come From?

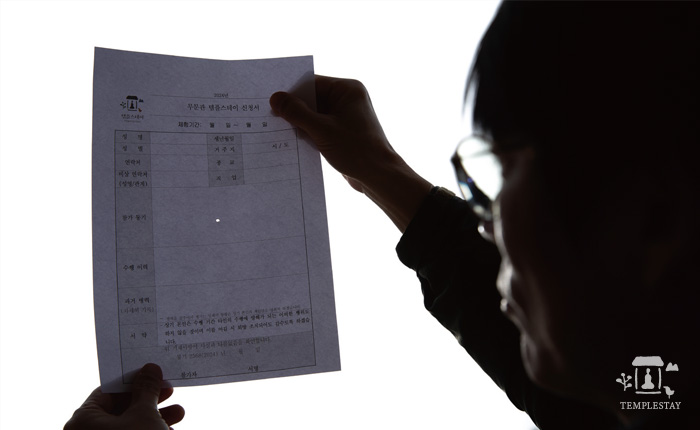

Unlike typical Templestay programs that offer diverse programs, Gapsa's Mumungwan focuses only on one thing, so the schedule is also simple. I arrived at the temple early and met with the Templestay team leader Lee Dong-ik who gave me a brochure and explained the program. Although it was a short 2-night-3-day basic course, he also warned me that something unforeseen could happen and suggested I not bring a knife in case I experienced some mental crisis. Just before entering Mumungwan, Ven. Taewon, the Templestay guiding monk, offered me a profound explanation.

That was it. In Mumungwan, you have to practice on your own. No one interferes or is involved in it. Of course, the old wooden door is fragile enough to be broken down with one's shoulder, but still one is locked in from outside like in a prison. Participants receive only one meal a day through a tiny opening not big enough to escape through, and practice day after day with a determination to attain enlightenment as the Buddha did: Mumungwan is such a fierce, solitary practice.

Ven. Taewon explained that hwadu practice is a form of “concentration meditation” and he compared Seon (Chan/Zen) and science, and Seon and Western philosophy. At first, his words seemed to cause my brain to cramp. Then he pierced a piece of paper with a ballpoint pen, hung it on the wall, and told me to look through the hole. I did as he instructed and had a mystical experience where I could clearly see the entire world through the hole. I nodded and understood each of his words. I didn't know if it was his intention to give me a hwadu, but I received this one sentence as my hwadu: “Where did the cow come from?” I fully accepted his words, that seemed to focus like light through a convex lens into a single hwadu that would ignite my consciousness.

“Where did the cow come from?” That was it. I heard a story once about a certain monk who was practicing meditation facing the wall, and he saw a cow coming in and out through a small hole in the window. He told his teacher about it, and the teacher asked, “Where did that cow come from?” After hearing the question and thinking about it carefully, the disciple smiled and attained great enlightenment. The moment I heard this story, it intrigued me, and I thought I got the idea, and then again I didn't. Should I say it tickled me? However, I was happy and shouted silently to myself, “I am going into Mumungwan with at least one hwadu.”

Weather Clear, Rain at 6 p.m.

Fortunately, I was not claustrophobic. Since there was no obsession or pressure to become enlightened, I can say Mumungwan was more comfortable for me than being home. I even felt that I could practice Mumungwan for at least a month. Having left my cell phone in the temple's care and without Internet or Netflix, I was absolutely all alone in room 7. I put the paper—on which Ven. Teawon had punched a hole minutes ago—on the wall, and sat down, straightening my posture.

“Where did the cow come from?”

My “prison” consisted of only a room, a bathroom, an opening to receive meals, and a window at the back. At times I felt like my body was expanding out into space, but that was clearly an illusion. Early in the morning, my ears pricked up at the distant sound of the bell calling people to the morning Buddhist ceremony. I also experienced getting wet along with the earth and grass when I became their spirit while listening to the occasional sound of rain. While squatting in the shower, I listened to the sound of the water flowing down my body and into the drain. It reminded me of a song.

At 11:30 a.m., my meal, neatly packed in an insulated lunch box, was delivered through the food slot; food had never tasted so sweet and delicious. Everything and everyone was helping me, but all I could do was sit and question, “Where did the cow come from?”Sometimes I saw the humor in it, but sometimes I felt guilty. Sometimes I just gave up and lay down on the floor stretching my limbs.

Whenever I found time, I colored in a mandala drawn on a sheet of paper placed on the desk, using the colored pencils provided. I eventually completed it. Day 1, day 2, and day 3… Time passed by quickly. It seemed like it hadn't been long since I entered, but before I knew it, the door suddenly opened and Ven. Taewon greeted me with palms together.

The Road Accessible from Everywhere

It is said that Gapsa's Mumungwan practice began when Ven. Jeongyeong—who first began practicing Mumungwan at Cheonchuksa Temple on Mt. Dobongsan—began doing it at Gapsa's dilapidated Daejaam Hermitage. The tradition of practicing meditation by isolating oneself in a closed space can also be found in Tibetan Buddhism, and although the practice may differ, it is also found in other religions, such as Carthusian cloistered monasteries.

In his book, Gateless Barrier, which summarizes 48 Seon Buddhist hwadus, Master Wumen Huikai said, “The Great Way is gateless, but can be approached in 1,000 ways. Once past this checkpoint, you can traverse the universe.” This is the concept where the practice of Mumungwan and the term “Mumungwan”—which symbolizes Seon Buddhism's Ganhwa Seon practice—cleverly intertwine.

Mumungwan practice is a concentration practice done in an isolated space; its goal is to open all the closed doors within oneself, escape the hell we create in our mind, and find freedom and the natural path to peace that is free of all obstacles. Although it usually lasts only 2 nights and 3 days, Mumungwan practice is considered the most special program that can be experienced at a Templestay as it is an old and powerful training tradition. “What I am afraid of is not that my answer might be wrong, but that the question within me and the hwadu which is my life disappear”; I kept this passage in mind, a passage written by a monk who published his practice diary after completing Mumungwan practice.

“I can’t say that I love myself, but I can look at myself with admiration.” This is what I wrote on the “Postcard to Myself” that will be delivered to me a few months after I complete my Mumungwan practice, postage paid by Gongju City; it should reach me in the fall.

What I Gained in Room 7

I really want to do Mumungwan practice again. Rather than locking myself in, I just want to close the door to the world and go deep within myself. After experiencing Mumungwan at Gapsa and later witnessing another man's death, I realized that life and death are clearly different. For about 20 minutes after he was taken off the ventilator, his pulse began to slow, occasionally pausing. He was in a closed intensive care unit—somewhat like Mumungwan practice—and I whispered to him passages from the Tibetan Book of the Dead.

“Concentrate your consciousness so that your mind doesn't wander. That thing called death has now come upon you. So, make up your mind and tell yourself, ‘I will use this death to extend a heart of love and compassion to all things as numerous as stars in the sky. I will strive to attain complete enlightenment. In the afterlife, I will become one with the origin of existence.’”

I don't know what enlightenment is or why I need to know who I am, and I don't know anything about what is what. However, I seem to believe completely in the Buddha's words that say all beings can become buddhas. Where did the cow come from? No matter what thought, what sorrow, what misfortune I find myself in, I have just one question, a question that returns to the origin through just one tiny hole; I just want to go back to Room 7 of Gapsa's Mumungwan.

Son In-ho is a walker who likes the songs of Ichiko Aoba, the paintings of Kang Yo-bae and Kim Myung-sook. He also likes poems and trees. While working at the Incheon Airport Logistics Center, he published his collection of poetry in Korean titled It's No One’s Fault.

Gapsa Temple

+82-41-857-8981

https://gapsa.org