Wind Chimes, Seeing the Wind

Text by. Im Taek-su Illustration by. Kim Sang-gyu

It is a spring day,

and the sunlight spreads like the soft sound of a bell.

In the silence I hear the sound of winter departing.

Suddenly, a long-ago memory about a mountain temple comes to mind.

The first time I went to a temple

was during a spring field trip in the sixth grade.

I remember as a child watching from a distance

as children screamed and ran away

from the four ferocious statues housed in the Gate of Heavenly Kings.

That year, I had won grand prize in a drawing contest,

and I later realized why my drawing was different from others.

I remembered the dancheong (decorative cosmic designs)

that I had briefly seen during a spring field trip,

so I used the barim coloring technique

(blurring hard edges and adding depth to colors by spreading water and pigment).

I painted the entire picture using this technique.

Sometime later, while in my 20s, I visited an old temple in Jeonnam Province with my girlfriend.

At that time, I was not a Buddhist, but I went into the main hall anyway to pay my respects.

As someone who lived a disciplined life and only followed social conventions, I naturally entered through the main hall’s central door, chose the largest and softest cushion, and bowed three times while facing the Buddha.

I knew nothing of temple etiquette.

When I left the main hall, I noticed a monk looking at me for a long time with his hands behind his back.

I don’t remember his facial expression.

I only remember the wind chime (punggyeong) swaying in the wind and making a clear sound under the eaves.

My old girlfriend and I had sat together on the earthen floor of the Hall of Immeasurable Life and listened to the sound of the wind chimes, but we have long since parted ways.

Spring flowers bloom one after another, the yellow cornelian cherry blossoms, pink peach blossoms, transparent white acacia tree blossoms, etc.

In the same way the absence of my old love feels natural, and my heart swells like a lotus blossom on a spring day.

Who was the first person to hang wind chimes on temple eaves?

Some people call wind chimes “pungtak” instead of the more common “punggyeong.”

Other names include: pungnyeong, cheomnyeong, cheomma, and geumtak.

What they all have in common is that they refer to bells.

In Chinese and Korean scriptures, they are referred to as “tak (鐸)” or “ryeong (鈴).”

Colloquially, the term punggyeong is used more often, and in academic circles, pungtak is more common.

The fish hanging under the body of the wind chime is called a pungpan or tail decoration.

It is a wide plate that catches the wind to move the bell’s clapper.

The fish shape commonly seen today appeared after the Joseon Dynasty, while before that, the pungpan were mainly shaped like leaves or clouds.

One of the stories that uses fish as a symbol is as follows:

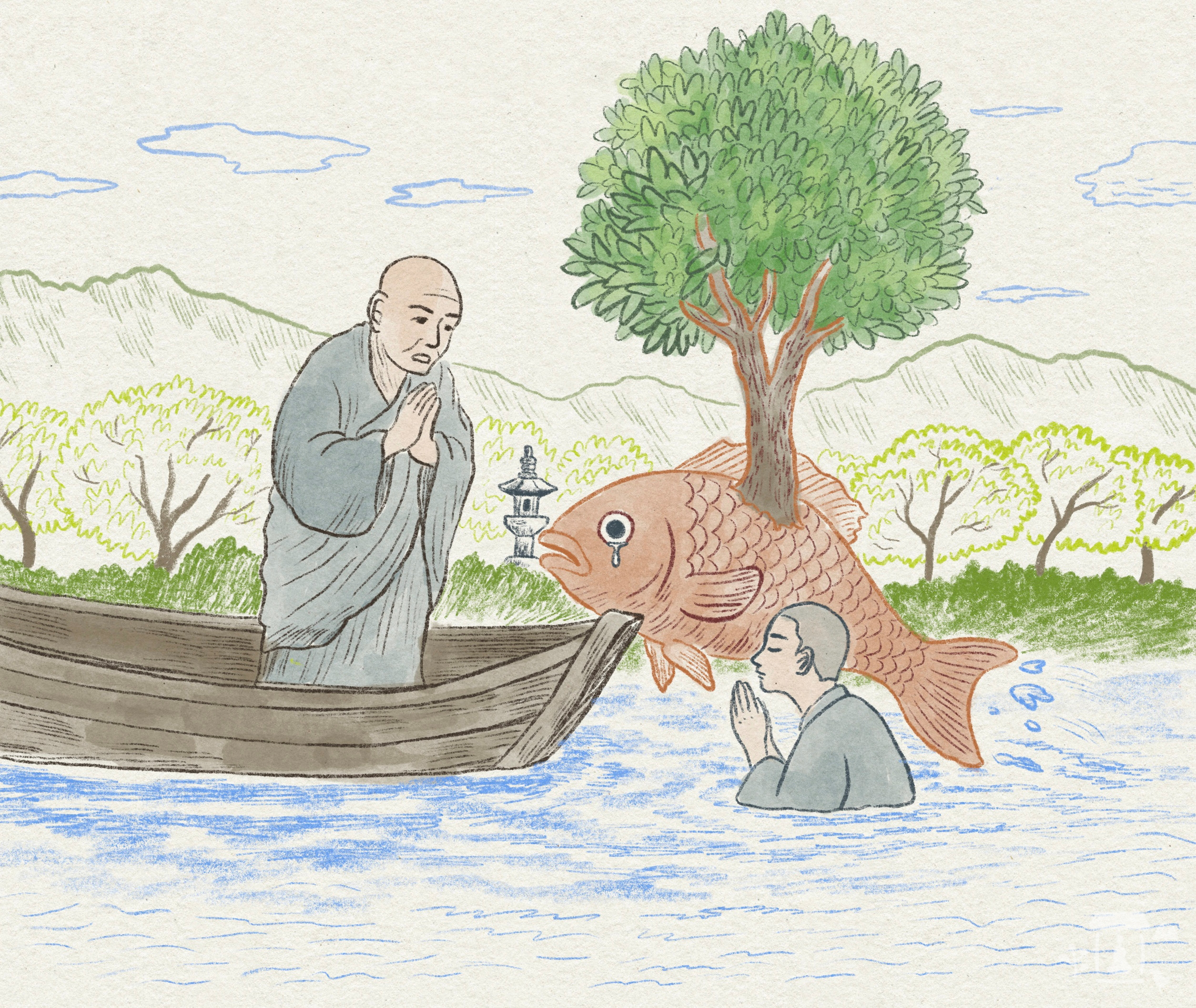

Long ago, an eminent monk had a disciple who neglected his training and was rather selfish.

This disciple became seriously ill and died, after which he was reborn as a fish.

However, a small tree grew out of his back and gradually weighed him down, causing severe pain.

One day, when the old monk was crossing a river on a boat, a fish with a large tree growing from its back approached the boat, weeping sadly.

When the old monk looked into the fish’s past life, he recognized it was his former lazy disciple.

The fish repented for neglecting his training and asked the old monk for a dharma talk to be liberated from his plight.

The old monk felt compassion for his former disciple and performed a Water and Land Ceremony to free him.

Then, he did as his former disciple requested, cut down a tree, and carved a wooden fish.

Fish do not have eyelids.

They do not close their eyes day or night, and even when they are dead, their eyes remain open.

That is why Buddhists began creating fish-shaped Buddhist utensils to remind practitioners to always remain aware.

I went to study abroad in France at a later age than most people.

I first studied French there, but eventually, living there became too expensive, and I couldn’t afford stay.

I returned to Korea, worked for a few years, and then returned to France for graduate school.

One of the reasons I chose France was because I did not have to pay tuition.

To prepare for the upcoming master’s thesis examination, I did not sleep for eighteen days.

Thinking back now, I can hardly believe it myself.

My advisor told me that a professor who was known for discriminating against foreign students was preparing a very strict examination.

I stayed up many nights preparing for the expected questions.

Three days before the examination, I collapsed with severe chest pain, and from that day on, I slept three hours a day.

I still vividly remember the studio I was renting at that time.

Covering the long balcony door were chiffon curtains that fluttered lazily in the sunlight, and above the door hung a cast-iron wind chime from which an iron fish hung at a slight angle, occasionally comforting me with clear chiming sounds.

The clear sound of a pungtak is an offering to the Buddha, and is intended to increase a practitioner’s wisdom and to remind all sentient beings to seek enlightenment.

When a fish is suspended in the air like that, one can imagine the blue sky as being a vast ocean, and oceans have a vast amount of water that can protect wooden buildings from fire.

In rare cases, pungtak were hung on the four corners of the crown on the head of a buddha statue, such as the Stone Standing Maitreya Bodhisattva at Gwanchoksa Temple in Nonsan.

Pungtak come in two general shapes: a bell shape (jonghyeong) and a trapezoid shape (jehyeong).

The bell shape can be either a traditional temple bell shape or a cylindrical shape, and in the case of the former, the front resembles an upside-down jar, like a temple bell from the Unified Silla period.

Trapezoid shaped pungtak have a bottom plane in the shape of a diamond or square.

The front is a trapezoid with a single curve at the bottom, and the sides come down in either a straight line or an entasis line (convex curve).

A Gilt-Bronze Pungtak discovered intact at the Mireuksa Temple Site dates from the Baekje Kingdom and is the oldest bell unearthed in Korea.

It is 14 centimeters tall and was discovered in 1974 during the excavation of Mireuksa’s east pagoda; discovered by the Mahan Baekje Cultural Research Institute of Wonkwang University.

This Gilt-Bronze Pungtak is trapezoidal in shape, narrow at the top and wide at the bottom, and the overall shape of the wind chime seems to reflect the style of a temple bell.

It has vertical bands decorating both sides of the body dividing the front and back, and connecting the upper and lower sections to a square lotus band.

A semicircular ring is attached to the top; there are two shoulder bands on each side of the shoulder area, and five small relief nipples are seen within the bands.

The most notable part of this pungtak is the lotus-shaped dangjwa decorating the front and back of the body.

Dangjwa refers to the place where the bell is struck.

A dangjwa is unnecessary on a wind chime, so having one here suggests it is simply copying the style of temple bells of the time.

“Old Bell at the Tower Gate of an Ancient Site” is an entry in Yeongaji, a record from the Joseon Dynasty written during the reign of King Sejo.

At that time, temple bells were being sought from all over the country to be used in the reconstruction of Sangwonsa Temple, so an old bell hanging from the pavilion gate of the Andong government office was selected and moved to Sangwonsa Temple.

The dangjwa resembles eight lotus petals and looks similar to a gilt-bronze wind chime.

The bell at Sangwonsa Temple has a straight line at the bottom, while Baekje’s Gilt-Bronze Pungtak is curved, like a Chinese bell.

During the Unified Silla Period, pungtak in diverse shapes appeared.

The horizontal cross section was either square, circular, or diamond shaped, and the surface could have patterns similar to bells or no pattern at all, showing a greater variety of appearances compared to the Three Kingdoms Period.

During the Goryeo Dynasty, trapezoid-shaped wind chimes became popular.

The increase in the production of these pungtak in Korea since the late Silla and early Goryeo periods was due to the influence of China, which had a preference for this style.

The shapes used included circles, diamonds, and hexagons.

Unlike before, the surface was freely decorated with various designs, including: lotus-shaped relief patterns, geometrical patterns in which two “gung (弓, arrow)” characters are placed back to back (bulmun), three intersecting circles (samhwanmun), three individual circles (samwonmun), buddha statue patterns, Sanskrit patterns, and animal patterns.

The wind chimes of this period clearly used Buddhist symbols.

The addition of a separate device called a chige (a cross-shaped clapper) to the bottom of the connecting rod, which was used to strike the four sides of the body evenly to produce sound, reflected meticulous craftsmanship.

These chige were mostly in the shape of a cross.

The pungtak of the Joseon Dynasty were much simpler than those of the Goryeo Dynasty, such as squares and bell shapes; and there were also trumpet shapes that were modifications of the bell shape.

Yiqie Jing Yinyi (The Sounds and Meanings in the Scriptures) says the sound of a wind chime represents the voice of the Buddha.

Wherever there is a pungtak, the teachings of the Buddha also exist.

Thus, the image of a fish, a creature free from all restrictions, came to be hung on the eaves of temple buildings and on the ends of roof stones on stone pagodas.

Neither sunlight nor the sound of a bell can be physically grasped.

However, we can warm our bodies in the sunlight, open our ears for a moment to the sound of wind chimes, and close our eyes.

The paths that the sound of wind chimes take when dispersed into the air must be 1,000 or 10,000.

Trees swollen with sap also freely make their own paths in the air as they spread their branches.

A wounded tree activates its own self-healing power and creates new callus tissue on its own.

The strongest wood on a tree is where a wound has healed.

Those who have left me and those I have left are now only blank spaces in my life.

Wounds leave scars, whether visible or invisible.

Nevertheless, we are now in the season where healing sunlight gently caresses those scars.

Lim Taek-su served as the Templestay team leader at a temple of the Jogye Order. He starts every day reminding himself that among all the things he has developed attachments to, nothing is eternally his.

Kim Sang-gyu is an illustrator and has completed the 4th class for Buddhist creators at the Jogye Order’s Bureau of Dharma Propagation. His books published in Korean include Black Stars and Pictures of Light and Wind, Goryeo Buddhist Paintings.