The Season of Fruit and a Bountiful Table

Bohyeonam Hermitage of Haeinsa Temple in Hapcheon

"A cool breeze begins to blow through the hot and humid air of late summer. It’s time to welcome a new season. Due to climate change, summers have become incredibly long, and as soon as fall seems to be just around the corner, it quickly turns into winter. Autumn has become even more precious. I long to capture its fleeting moments and cherish it as long as possible. Is there a better place to savor autumn than a mountain temple? Let’s shake off the torpor of the sticky summer and appreciate the sounds of the wind chimes in the autumn breeze. If this atmosphere is enhanced by a mountain temple’s autumn meal, there is nothing more to ask for"

The Season to Travel like Clouds and Water

Perhaps autumn is like a long exhalation. It’s a time to release the heat we inhaled so much of during summer, and with that deep exhalation, the sky clears and fruits ripen. In the scorching heat that still hovered above 30 degrees Celsius at midday even after Cheoseo (the traditional end to the summer heat), I visited Bohyeonam, one of Haeinsa Temple’s hermitages on Mt. Gayasan. Deep in the mountains, where Hongnyudong Valley lies, the air at Bohyeonam was distinctly different from the city. Even without air conditioning, a cool breeze blew in to help evaporate the sweat. The scent of a new season wafted into my nostrils. In the temple courtyard, cosmos blossoms fluttered against the blue sky, heralding the beginning of autumn. The temple compound was immaculately maintained, as if no part of it had been left untouched by the nuns.

Bohyeonam is a hermitage where nuns are trained. It was established in 1973 through the vows of Hyechun Seunim (1919–1998), a prominent nun in the Korean Buddhist community who served as the first president of the National Bhikkuni Association of the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism. Samhaeng Seunim, who now serves as the superintendent and proctor of Bohyeonam, guides guests to their overnight accommodations. Because the hermitage doesn’t offer Templestay programs, and thus, doesn’t have a separate space for visitors, she kindly offered us a monastic room to sleep in, even providing clean bedding. After quickly unpacking, we shared a conversation with Samhaeng Seunim over tea. Since the temple observes the practice of “no meals after midday,” she offered us fruit in lieu of a formal dinner offering and brought out ripe watermelon and grapes. She explained that she went out of her way to the market to buy the best fruit. Biting into a grape, I noticed a sweetness unlike the imported grapes I usually eat. Even before I taste the temple food, my taste buds are already in a state of anticipation.

In the fall of 1989, Samhaeng Seunim entered monastic life at Bohyeonam Hermitage under the tutelage of Hyechun Seunim. Now she is about to enter her 36th autumn here. For monastics, autumn marks the end of the 100-day summer retreat, after which they shoulder their knapsacks and visit various temples, traveling from temple to temple “like clouds and water.”

According to the Attendance Record of the 2025 Summer Retreat, 15 nuns, including Samhaeng Seunim, practiced at the Bohyeonam Seon Center this summer. The Bohyeonam Seon Center is an ideal place for a Seon retreat, free of humidity and with good ventilation, as well as being imbued with the energy of Mt. Gayasan. After so many days of intense Seon practice—seated firmly on a mat while singlemindedly investigating a hwadu—it is now time to freely embark on a journey, even though they may not travel far. Just experiencing the flow of the clouds, the sound of a stream, the fragrance of flowers drifting in from afar, and becoming one with the water, is also a kind of journey that brings a sense of freedom.

Autumn Fruits Enriching the Vegetable Garden

Next morning at 4 a.m., the mountain temple’s day begins with the “temple ground chanting.” The pre-dawn sky is filled with stars, a sight rarely seen in the city. And the sound of the temple bell that follows awakens everyone and everything.

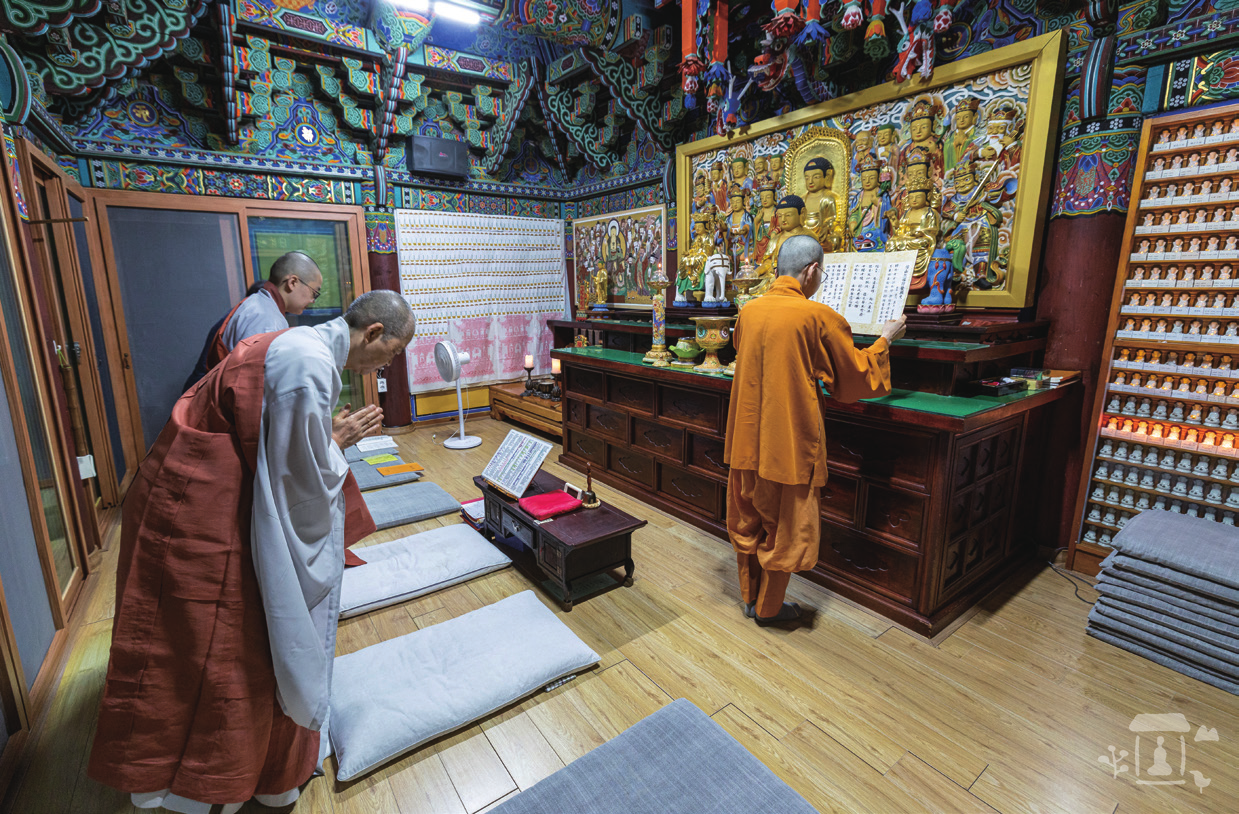

At Bohyeonam Hermitage’s dawn Buddhist ceremony, they recite the Surangama Mantra, passing on the teachings of Seongcheol Seunim, whom Hyechun Seunim respected as a great teacher. It is said that reciting the Surangama Mantra empowers one to overcome all obstacles to their Buddhist practice. Kneeling with joined palms together, I focus my heart on the nuns’ recitation, which sounds as beautiful as sacred music. Though the meaning is incomprehensible to me, the language of mystical and profound truth warmly envelops infinite space.

Bomun Seunim, a third-year student at Bongnyeongsa Monastic College, strikes a moktak (wooden handbell) to signal the start of the breakfast offering. Having stayed at Bohyeonam during her summer vacation, she plans to return to college at the start of the fall semester. For breakfast, rice porridge was served with simple vegetable side dishes, yogurt, nuts, and red tomato soup. This was the first time I ever saw tomato soup served at a temple. Boiled without any additives, the soup was both sweet and sour at the same time. It was a refreshing taste that woke me up.

At 7 a.m., the nuns gathered in small groups in the expansive vegetable garden at the entrance to Bohyeonam Hermitage. They were there to pick vegetables before the sun got too hot. The garden was filled with all sorts of vegetables: chili peppers, Korean zucchinis, cucumbers, eggplants, cabbages, autumn radishes, chards, and beets. They had also planted 400 heads of napa cabbage for kimchi. It’s no exaggeration to say that tofu and bean sprouts are the only ingredients purchased outside the hermitage. Autumn is especially busy for harvesting vegetables.

On the fence located on one side of the vegetable garden, clusters of gourds hang alongside white gourd flowers. The gourds are surprisingly heavy. At Bohyeonam Hermitage, they reportedly make a soup from the gourd’s inner flesh during the Chuseok Holiday. The seeds and skins are removed, the flesh is cut into bite-sized pieces, stir-fried in sesame oil, and then boiled with veggie stock, sometimes adding wild pine mushrooms.

Yukgeuntang is well-known as a dish often enjoyed by Hyechun Seunim. This soup, made with six root vegetables—taro, burdock, radish, carrot, potato, and lotus root—is said to help replenish one’s energy. Making Yukgeuntang requires peeling the burdock and lotus root. When Samhaeng Seunim was a postulant, her hands were often blackened after hours of peeling. She reminisced: “Once, Hyechun Seunim—who then resided at the National Bhikkhuni Center—came to Bohyeonam and saw the postulants’ blackened hands. She asked, ‘What’s wrong with your hands?’ after which I remember her saying, ‘Don’t make Yukgeuntang anymore. I don’t want the food I eat to disfigure the postulants.’”

It’s said that during the week-long period of Undaunted Practice, during which nuns practice without sleep, they are offered boiled thin millet gruel or yeot (Korean taffy made from grains), of which they ate one spoonful each day.

Whether cooking or doing Buddhist practice, everyone prefers easy and quick shortcuts, but sticking to the basics, even if it takes longer, is what makes everything taste better.

A Tradition of Silently Preserving Temple Cuisine

Today, the main ingredient on our mountain temple table is potatoes. For the lunch offering to the public, Samhaeng Seunim will prepare Gangwon-do-style potato sujebi (hand-pulled dough soup), made entirely with potatoes and no flour. She says she learned this dish from the proctor nun when she stayed at Woljeongsa Temple’s Yuksuam Hermitage. For 15 servings, one must prepare 25 medium-sized potatoes. Peel and grate the potatoes, then lightly sprinkle with salt to prevent browning. Tip: “While it’s convenient to blend the potatoes, the end product is so fine that it resembles soybean powder. Grating them, even if it’s a bit more laborious, preserves the fiber and creates a chewier texture.” Whether cooking or doing Buddhist practice, everyone prefers easy and quick shortcuts, but sticking to the basics, even if it takes longer, is what makes everything taste better.

Wrapping grated potatoes in hemp cloth to drain the water is no easy task, and squeezing them with your hands requires some practical wisdom to squeeze out all the remaining moisture. Wrap the grated potatoes in a hemp cloth and place it on a cutting board with a basin underneath to catch the starchy water. Fill a bucket with water and press it down on the hemp cloth. The weight of the bucket will help drain the water out of the grated potatoes, and the starchy water will collect in the basin. Leave the grated potatoes weighted down under the bucket for about three hours, until the starchy water settles in the basin. Pour out the water and knead the starchy residue in with the potatoes. Now you’re halfway done.

Thirty minutes before the moktak is struck to announce the meal offering, cooks begin to make the ongsimi (potato dumplings). They take a piece of dough, the size of the first joint of a thumb, and, using firm pressure, shape it into a flat, round shape. They then firmly press the dough together to ensure the mixture sticks together well to create a chewy texture that won’t come apart when dropped into boiling water. They then add ongsimi, zucchini, red chili pepper, and other vegetables to the veggie stock (produced by boiling kelp, shiitake mushrooms, radish, and prickly castor oil sprouts), and the potato sujebi is done. It is served with homemade pickled melon, made with end-of-summer melons, and with pickled Chinese pepper (sancho). It’s the perfect, yet refined, autumn meal for any monk/nun. It’s not noodles, but it’s definitely a dish that will bring a smile to monastics, a dish that will satisfy everyone, from those who just arrived on March 1st this year to the senior monastics.

"These days we make temple dishes that suit younger monastics’ tastes—pasta, pizza, even tteokbokki. But in temple style we’ll, say, bake thin-sliced potatoes as a pizza crust, or steam kabocha stuffed with mozzarella.”

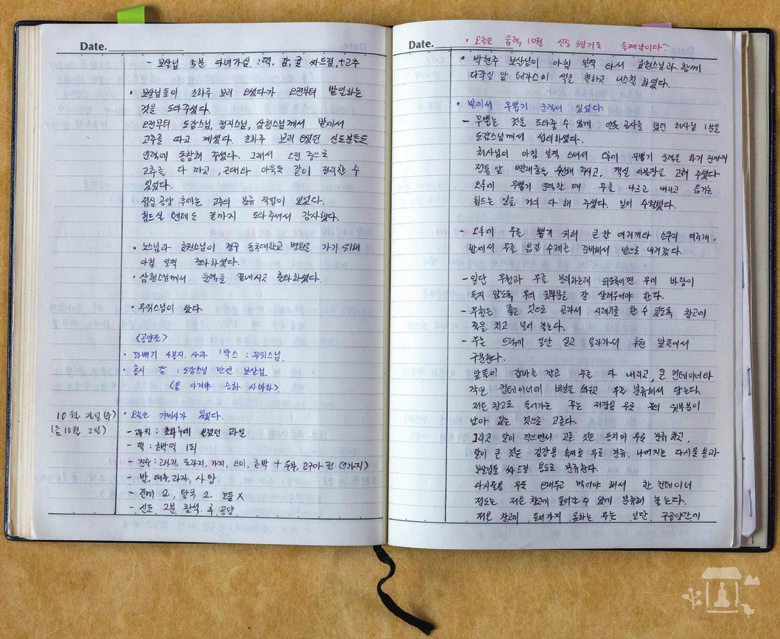

While temple food culture evolves with the times, Bohyeonam Hermitage maintains one age-old tradition: the Proctor’s Journal. This meticulously handwritten notebook details the menu, ingredients, and recipes for temple events, including the memorial ceremony for Hyechun Seunim and “repentance prayers in forty chapters,” as well as a list of the offerings received that day. Following the offering list, the notebook is inscribed with the mantra “Om Ariya Sangha Savaha,” which is recited when receiving a donation to express gratitude. The notebook is imbued with a spirit of gratitude, even for the smallest offerings.

According to the Proctor’s Journal for the fall of 2022, October 30th (the 6th day of the 10th lunar month) was gimjang day (annual preparation of kimchi for the winter months). At a temple, kimchi is usually made before the start of the winter retreat, so this year’s kimchi season is just around the corner. They’ve also planted 400 heads of cabbage for kimchi-making, and the autumn radish and chili pepper harvests have been good, so I can imagine how delicious it will be without even tasting it. At Bohyeonam Hermitage is a lotus pond shaped like the Chinese character for “heart.” As I gazed at the pond, the word “heart (心)” pierced my heart like a hwadu. Samhaeng Seunim said: “They say the sky in Tibet turns purple at sunrise, but the sunrise I saw from Bohyeonam Hermitage was the color of a ripe persimmon. The red deepens as the weather gets colder.”

Unfortunately, the cloudy weather prevented me from seeing this persimmon-colored sky that morning, but I think I’ll be reminded of the dawn sky at Bohyeonam Hermitage this fall whenever I see a ripe persimmon.

"While temple food culture has evolved with the times, Bohyeonam maintains one tradition that has endured since ancient times: the Proctor’s Journal."