What Do You Protect and Live by Today?

Haeinsa Temple in Hapcheon—Baengnyeonam, Huirangdae, and Gugiram Hermitages

"Years ago, when I was wandering around with a backpack, I’d been to Bodh Gaya and Gaya in India, but this was my first time visiting Mt. Gayasan in Korea. Excited, I woke up at 4 a.m., opened the window, and saw a world drenched in autumn rain. It was no different from the rain that had been falling for the past few days, but the mind of the one watching it had changed. It seemed as though a “rain of nectar”—said to banish all worldly troubles—had fallen throughout the night. Thus, in the autumn-tinged dawn air, I took a series of vehicles and headed to Haeinsa Temple, a 1,000-year-old temple nestled in the embrace of Mt. Gayasan"

One Is Many, Many Are One, a Small City of the Buddha-Dharma

As I approached Haeinsa Temple, a long tunnel of trees stretched on both sides of the road. And while passing through this arboreal tunnel, I prepared myself to leave the secular world behind. The tunnel played the role of a One Pillar Gate for me. At the end of this long tunnel, Haeinsa Temple finally appeared. Although it is called a “temple,” the sheer number of buildings and hermitages made it impossible to take in the entire compound at a glance, or how much ground it covered. Angkor Wat—with its scattered small temples that require several days to see—briefly came to mind. My first impression of Haeinsa Temple was that it was a small “city of the Buddha-dharma.” Thankfully, I was able to explore the temple compound in detail under the guidance of Hyeonsa Seunim, Haeinsa’s Templestay guide monk. He joked that since he had never left Haeinsa Temple since becoming a monk, he was essentially working from home. His constant banter made me relax. Perhaps I had been unconsciously tense, as Haeinsa Temple is widely known for its strict discipline as a comprehensive monastic training complex. Our first stop was Baengnyeonam Hermitage, located at the highest point among Haeinsa Temple’s hermitages. Despite the drizzle and thick clouds, the expansive view was refreshing to the eyes and mind. The splendid Baengnyeonam Hermitage— nestled between large rocks in a pine forest—resembled a buddha’s palace. The stone lotuses planted here and there seemed ready to bloom in the pouring rain. Hyeonsa Seunim informed me, “Baengnyeonam Hermitage was actually quite small when Seongcheol Seunim resided here. Women devotees who have been worshiping here for a long time find it unfamiliar when they visit now. They say it has changed so much.” As a first-time visitor, just seeing Haeinsa’s Wontongjeon Hall—where Seongcheol Seunim used to reside—was enough to give me some insight into his spirit: he owned only two sets of ragged monk’s robes his entire life and even cut a single piece of toilet paper into three or four pieces to conserve paper. Looking at the countless acorns that had fallen in the wind and rain, I suddenly wondered, “Is life really so difficult? When the wind blows and the rain falls, acorns fall to the ground, and that’s all there is to it. They fall, roll around, and end up as squirrel food. What else could possibly happen?”

On our way down, we stopped by Huirangdae Hermitage. The charmingly decorated garden, complete with small rubber shoes decorated with flower designs, captivated everyone with its picturesque charm. Gyeongseong Seunim, the superintendent of Huirangdae, happened to be there, so we offered three prostrations in greeting and conversed with him over tea. Is there anything better than a warm cup of tea in the cold rain? A replica of the seated statue of Great Master Huirang was enshrined there, which seemed to resemble Gyeongseong Seunim. When someone pointed this out, everyone agreed and smiled. Were we drinking the same tea once served by Great Master Huirang? It was getting late, so we decided to visit Gugiram Hermitage the next day. We then returned to Muajeongsa Hall, our Templestay accommodation at Haeinsa Temple. Many say that the world of the Flower Garland (Avatamsaka) can be summed up in one phrase: “One is many, many are one.” We visited many places and met many monks in one day, and they themselves were all part of Haeinsa Temple, the very essence of Haeinsa Temple. I reflected on the day while listening to the sound of the rain and the powerful sound of the stream swollen by the rain. I then fell into a deep sleep.

Gugiram, a Hidden, Serene Hermitage

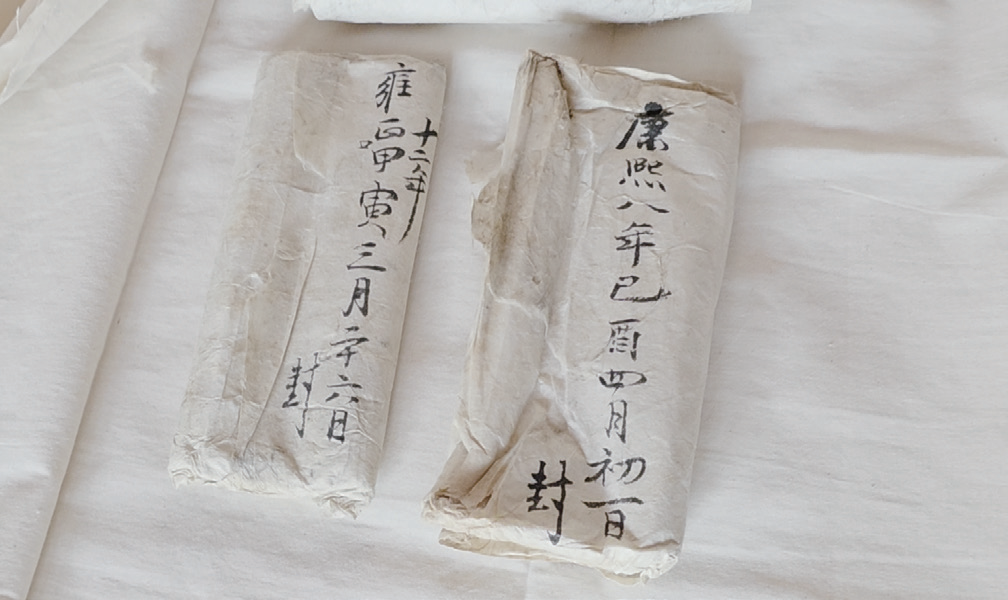

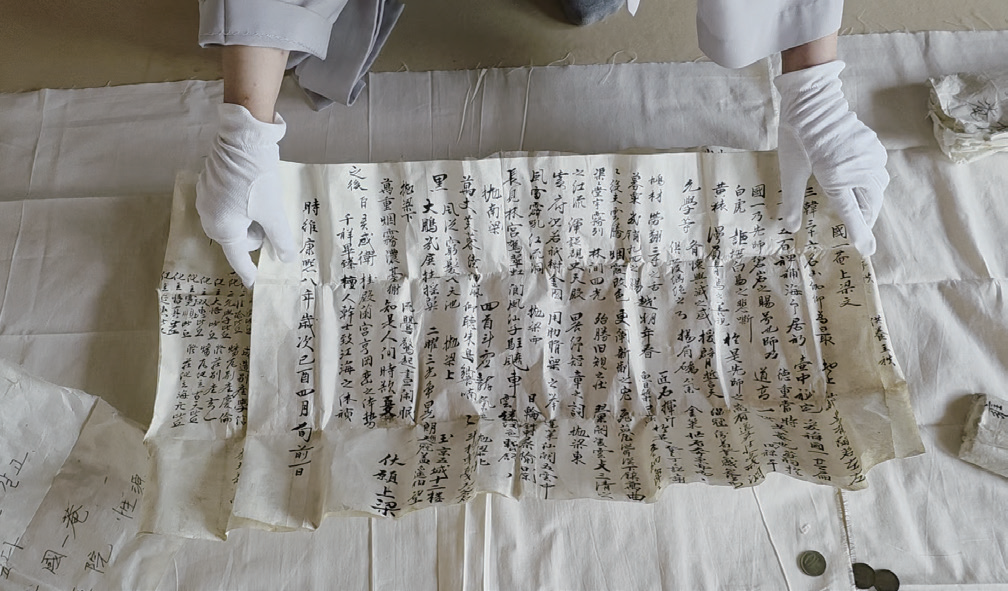

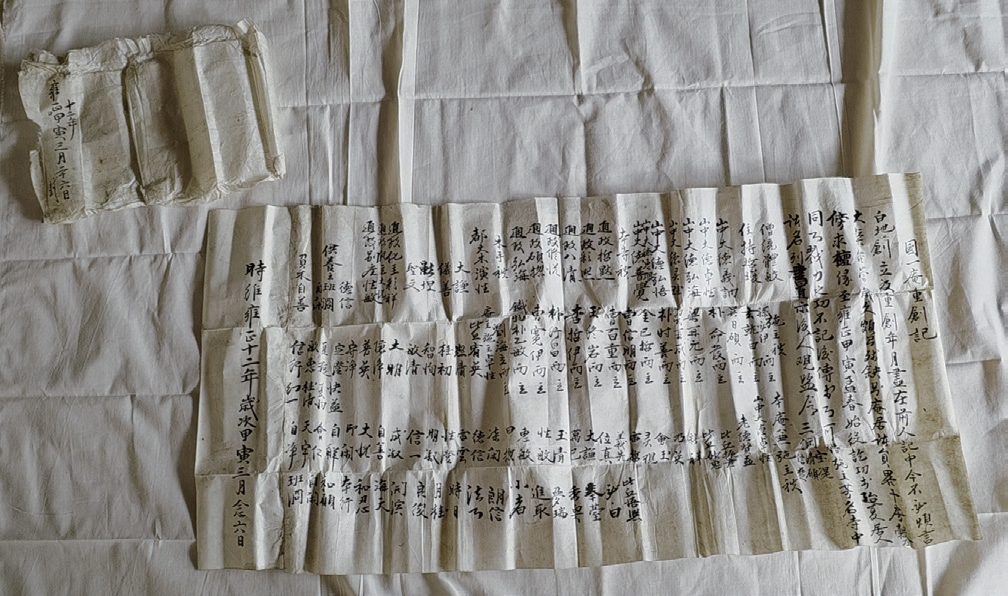

The next day, after the early dawn ceremony and breakfast offering, we wandered around the temple compound until we came across Gugiram Hermitage. Upon entering, we immediately noticed the Inbeopdang still under construction. Inbeopdang refers to a buddha hall where buddha statues are enshrined and one monk/nun resides. During restoration work last July, a ridge beam scroll inscribed with “8th year of the Kangxi era (1669)” was discovered, prompting a halt to all construction. With concrete evidence proving it to be the oldest Inbeopdang in Korea, the hermitage is now off-limits until it receives a cultural heritage designation. The name “Gugiram” comes from the posthumous title given to Byeogam Gakseong Seunim for his contribution to the construction of Namhansanseong Fortress during the reign of Joseon’s King Injo. However, today, its reputation is more cherished as a nunnery than for his patriotism. It was Seongwon Seunim who, through painstaking efforts, reestablished this dilapidated site into a nunnery. I asked Myeongbeop Seunim—who became a nun under the tutelage of Seongwon Seunim, and is currently the superintendent of Gugiram—to tell me more about the hermitage. “Gugiram was a well-hidden hermitage, but it played a vitally important role. From the 1970s to the 1990s, when everyone was building large temples and hermitages, our hermitage, due to a lack of money, was left undeveloped. Even now, the road leading up to Haeinsa Temple on weekends is as crowded as any city, but once you get to this hermitage, it’s a true temple compound.” She said this with some laughter. Of course, even if the donations from numerous visitors had been greater, preserving the old temple as it is wouldn’t have been easy. The same is true of the hermitage’s traditional-style outhouse (haewooso). She said the ridge beam scroll on the building indicates the outhouse is over 120 years old. Since it’s the same outhouse our ancestors used, it is uncomfortable and smelly, and no devotee would want that. But that didn’t seem to be the case. She said: “When I first came here, the excrement had to be taken away, so I asked a friend who practiced natural farming to do it for me. But later, as I was taking out the excrement, amazingly I noticed a fragrance. Farming taught me that what rots isn’t dirty, and what doesn’t rot is dirty. Some people use plastic or non-biodegradable vinyl because they think it’s clean, but it’s not. Using a modern flush toilet also uses three times more water than a traditional outhouse.” She said she didn’t think anyone would bother with the tedious task of removing the excrement from the outhouse. Who else would preserve the traditional outhouse if she didn’t? She said she thought it would be better to make it a cultural property so no one would tear it down or alter it. So, she planned to have it designated a folk cultural property, and later announced with great excitement that she would use the excrement as compost next year.

Continuing the Original Message

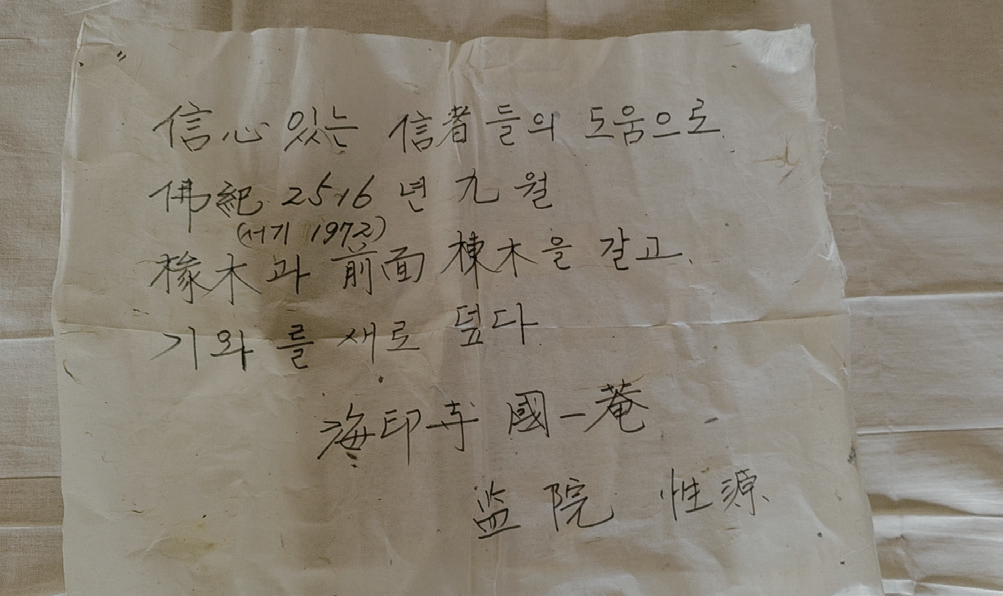

Our conversation naturally led to the story of Seongwon Seunim and the ridge beam scroll. Seongwon Seunim arrived at Gugiram in 1958 and began fixing everything that was falling apart, starting with the flat stones used for floor heating system. She then established a Buddhist nuns’ Seon center there. At the time, Gugiram was the only hermitage with a Seon center, aside from large main temples. Unable to afford replacing the rotten rafters, Seongwon Seunim went behind Baengnyeonam Hermitage to cut down trees herself, only to be arrested by the police. However, she pretended to be a little wonky and foolish, so they let her go. With this wisdom, she protected Gugiram. She even secured a hanok gate for the hermitage with multiple locks and wooden blocks to prevent anyone from entering and taking the portrait of Gakseong Seunim. Otherwise, it could have easily been sold or lost. The ridge beam scroll, discovered during renovations in 1972, was carefully wrapped in hanji and later returned to its original location. So, the reason Gugiram was preserved wasn’t simply because of its lack of wealth. Someone protected it, and now Myeongbeop Seunim continues to preserve its buildings, history, and value. She said: “I really believe that certain traditional things should be preserved. When I said I was leaving the Inbeopdang as it is with its under-the-floor heating system, monks came and praised me, saying I did the right thing. In fact, this traditional heating system is more environmentally friendly and futureoriented now.” Again, for something to be preserved means someone must protect it. Preservation is a human activity, but it can’t last forever. However, as long as there’s someone protecting something, it won’t disappear, but will remain and continue to speak to us. As I left the One Pillar Gate, hoping that Gugiram would soon become a cultural heritage site, the majestic sound of the Dharma drum I’d heard during the dawn Buddhist ceremony and the words of Myeongbeop Seunim somehow merged in my mind. Why? The Dharma drum is played alternately by two monks, and the most moving moment is the moment of exchange. To ensure the sound is never interrupted, the second monk comes and strikes alongside the first, matching the note and rhythm, while the first monk backs away. The drumming of both continues as one. That is a kind of inheritance, a continuation of the original message. Perhaps that resonance won’t last long for me. Now, I must return to the suffocating city and resume my old, hectic life. But sometimes, when I feel too pressed upon, the sounds of the Dharma I heard here will slowly come back to me, reviving my mind. Like the “Ocean Seal” on the surface of a calm sea surface, I will glimpse clearly again the true nature of all things. As I was leaving, I looked back at Mt. Gayasan, still clad in its white raincloud hat, quietly chuckling, as if to say, “For those who have something to protect, great joy is theirs. I ask you. What do you protect and live by today?”

Hwang Yu-Won made his literary debut in 2013, when he received the New Writer’s Award from the Munhakdongne. He is currently active as a poet and translator. His poetry collections include: Pond of the White Deer and Supernatural 3D Printing. His translated books include Moby Dick and Wuthering Heights. He has received the Kim Su-yeong Literary Award and the Contemporary Literature Prize.