A Simple Meal for

Students on the Path

Unmunsa Monastic College in Cheongdo

Text by. Jeong Tae-gyeom Photo by. Ha Ji-kwon

The power of a meal is significant. Only foods that

are prepared wholeheartedly for others—not for

convenience—has this sort of power. Meals made

in this way move the heart, not just the tastebuds.

This may be another aspect of what people call

“temple food” which we have not paid attention to.

Prayers to the Kitchen Deity

As always, morning at a temple starts at 4 a.m.

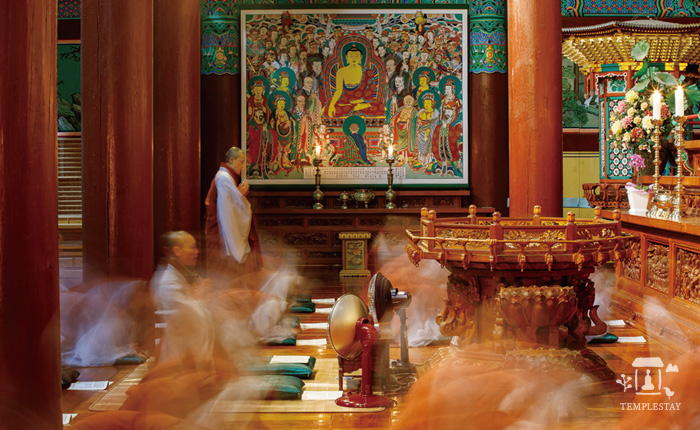

The mountain gate opens and the dharma drum sounds. While the dharma instruments sound one after another to purify the dark surroundings, the nuns head to the buddha hall in neat, orderly lines.

And then the predawn ceremony begins. I was once captivated by this predawn ceremony that wakes up the Buddhist realm before the sun rises. It happened here at Unmunsa Temple. Located deep in Cheongdo county, the temple is home to a monastic college for nuns. The sound of novice nuns chanting in sync with the beat of the wooden handbell could not have been more sincere. The chanting was elegant and pure but solemn at the same time.

The temple compound and the world I live in are two different worlds, but I feel like they connect and resonate with each other here. The sounds I hear resonate in my heart. I can't forget the lingering feeling of the early morning when I first saw this predawn ceremony, performed neatly and concisely. The voices of the participants chanting wholeheartedly in unison stir the emotions of the listener. Professor Yu Hong-jun, former head of the Cultural Heritage Administration, said this about the ceremony in his book, My Cultural Heritage Field Trip - Mountain Temples.

“A visit to Unmunsa Temple is not complete without the experience of watching or participating in the predawn ceremony. If waking up that early is too difficult, you should at least watch the evening ceremony. Only then can you say you have experienced Unmunsa Temple.”

If you have ever seen or heard the predawn ceremony, you'd have to agree. But the world has changed. Student nuns—which once numbered 250 or 300—now number only about 50 because fewer and fewer people choose to become a monastic.

However, the power of the chanting is not diminished whether there are 50 or 300 people. Even though the world has changed, the hearts of those who choose the path of an ordained practitioner remain the same.

The predawn ceremony is a ritual everyone in the temple must attend, but exceptions are made for some, like those responsible for cooking in the “gongyang-gan.” Even people who know temple culture well rarely think about this. After the predawn ceremony, the assembly must immediately attend the breakfast offering. In order to stay on schedule, those in charge of preparing the breakfast offering cannot go to the predawn ceremony. While everyone else is praying, they build the fire, prepare the vegetables, and season the soup. The only thing they can do is briefly go into the Jowangjeon—where the kitchen deity is enshrined—and pray when the food is almost ready. Ven. Seojun, the proctor nun in charge of all matters concerning meal preparation, stayed in the Jowangjeon for about 5 minutes in silent prayer. I asked her, “What did you pray for?” She glanced at me and answered with a shy smile.

“I prayed for the people who prepare the food to not get hurt or get their feelings hurt. I also prayed that people will be comforted by the food we make. I pray with that in mind every day.”

Some Things Should Remain the Same Even as the Times Change

Food is like that in general. The value of food is diminished when you only eat whatever food is available, but if you eat with mindfulness, it provides nutrients for your body to function, while also comforting and nourishing your mind. Therefore, preparing food for others is an altruistic act. They take up the knife not for themselves but for others.

This is the mindset that those in charge of preparing temple food must have. No matter how the times change, this is the one thing that does not change and should not.

The time allowed for meal preparation is about two hours. In the meantime, those in charge start by preparing the ingredients, cooking them, seasoning them, and filling bowls. No matter how many people are working, there is never enough time. Moreover, on average, there are 8 to 10 dishes to make. For the Saturday evening meal, there are 9 different dishes. They put the mixed-grain rice into the cauldron, and begin preparing the radish and bean sprout soup by boiling broth to which kelp is added. They put kimchi that has fermented for two years on the fire, add vegie stock, and begin cooking.

It is sometimes difficult to prepare meals at one's home, where only two or three side dishes are served, but those in charge of temple meals prepare 8 to 10 dishes, three times a day. That's why their hands move quickly. What is made clear during the process is that the recipe is not complicated. That is the character of Korean food in general. There is one thing that all chefs agree on: the best cuisine preserves the taste of good ingredients. Temple food is exactly like that. It is simple. Only then can the full flavor of the ingredients come out. What makes temple food different is that no part of a plant or vegetable is thrown out. In restaurants and other dining establishments, only certain parts are used and the rest is thrown away. Not so at a temple.

When making soup stock with kelp at most dining establishments, they remove the kelp when the water starts to boil, saying it tastes bitter. At Unmunsa Temple, it is the opposite. They boil the stock fully until all the flavor in the kelp is gone. When the kelp is removed from the stock, if it still looks usable, they use it again. Food is essentially a means of extending one's life by sacrificing the lives of others. Kelp is also a living thing, so it is the job of a temple chef to ensure that it is used to its fullest potential. That is how we ensure that taking another life is not done in vain. After boiling for a while, the soup turns brown, and then shredded radish and bean sprouts are added. That's it. It's neither lengthy nor complicated.

What is commonly called “gang-doenjang” is a kind of seasoned, cooked soybean paste, but in Unmunsa's kitchen it is called “ppak-ppak-jang.” First, finely chopped radish, potatoes, and zucchini are stir-fried, and then doenjang (Korean bean paste) and gochujang (Korean chili paste) are added. In other temples, it is common to add veggie stock without first stir-frying, after which it is boiled. At Unmunsa it is lightly stir-fried and then rice water (the water left after rinsing the rice) is added to increase the amount and adjust the thickness. The timing of the proctor nun to complete the dish by adding rice water is amazing.

Pre-trimmed burdock leaves are steamed lightly and served. Ven. Seojun said that among the vegetables used in wraps, burdock leaves are the most fragrant. She picked up a few steamed burdock leaves, touched them, and tasted them. She put some ppak-ppak-jang onto one leaf and checked the seasoning, proclaiming it “cooked well.” She then prepared another wrap and handed it to me.

It was neither too soft nor too tough. It chewed well and dissolved quickly. At first, there was a savory aroma, but after a short while, a bitter taste spread throughout my mouth. Bitterness enhances one's appetite. Immediately afterward, the heavy aroma of the soybean paste emphasized the taste. It still had a slightly spicy taste, and well-chopped vegetables complemented the chewy texture. It was enough to make even a person with no appetite finish a bowl of rice in no time.

How to Plan Daily Meals at a Temple

The time allowed for meal preparation is always tight. Cooking is invariably like that. It is never a leisurely task. As soon as the food is served, a line of people is waiting to eat. This is because a hungry stomach makes them walk faster than the hands that serve the food. Watching carefully each person as they eat and making sure the food doesn't run out, the persons in charge of meal preparation can finally relax.

In such a regimented daily life, how on earth does she plan three meals a day? It cannot be organized haphazardly, and it must meet standards. Ven. Seojun smiled broadly. She began to explain quietly, admitting it was a pretty daunting task.

“There are rules. When tofu is served, greens have to be leafy vegetables to supplement nutrition. When tofu is not served, root vegetables are served to make you feel you have a full stomach. If this or that doesn't work, we sometimes serve cheese. We also prepare beans or nuts braised in soy sauce to ensure there is adequate protein. If the weather is cloudy or chilly, we prepare a porridge called “gaengjuk” or a rice cake soup called “gaengtteokguk.” When you have body aches or feel cold, this will raise your body temperature. That is why, when planning the menu, we have to check the weather in advance.”

The daily menu should be planned at least 3 days in advance. Since the weather can change rapidly, it is impossible to plan beyond that. Since Unmunsa Temple is located in the mountains, changing weather patterns create more complications, and adapting to these changes is the most difficult part of meal preparation.

As I listened to her explanations about planning meals, two dishes caught my attention: gaengjuk and gangtteokguk. These are typical local dishes in Gyeongsang Province. In the past, when food was scarce, they were often eaten here. Both dishes are boiled with kimchi. If rice is used, the dish is called gaengjuk or gaengsigijuk. If you add kimchi to rice cake soup and boil it, it is called gangtteokguk. These local flavors are also apparent in Unmunsa's kitchen, located in North Gyeongsang Province.

Since I heard sujebi would be served for the lunch offering the next day, I was hoping they might add kimchi to it also. However, they said it would be a typical sujebi with clear broth. To make sujebi, the dough is prepared beginning at 5:30 a.m., after which it is refrigerated for about three hours to let it mature. At 10 a.m., the dough is kneaded for a long time, and one hour before the lunch offering, the dough is spread thin, torn into bite-size pieces by hand and added to the soup stock (along with a healthy dose of sincerity) to make sujebi. The common perception that sujebi is simple to prepare is not correct.

Another dish that caught my eye was dumplings (mandu). They fry them and serve. People think that dumplings “naturally” must contain meat. This is the result of getting used to what is sold on the market, and it is probably why people raise their eyebrows when you say you eat dumplings at a temple. However, dumplings are nothing more than a filling wrapped in dough. Even if you only add vegetables as a filling, it is not strange at all. Nowadays, people's awareness has improved, and a store in Busan makes and sells vegetarian dumplings. Instead of meat, they use tofu, mushrooms, and peanuts. The peanuts are coarsely ground to make the dumplings crunchy. The dumplings' unique nutty flavor attracts customers to this store. These dumplings are one of the delicacies found at Unmunsa.

What is obvious in all these meals is a consideration for the student nuns who study here. Everyone, including the proctor (wonju) and the nun in charge of side dishes (byeoljwa), have experienced being a student and know the inner thoughts of the student nuns well. They know what is difficult and necessary at different times, so they pray and do their best to prepare each and every meal to maintain sincere concern for their students.

A Seasoning Called a Sincere Heart

Misunderstandings are frowned upon. People believe that the food monastics eat is something special, but that is not the case. There is nothing special about it. The cooks in a temple kitchen just don't waste any ingredients given to them; they just cook with total dedication and sincerity. That is why it is so simple. In addition to this simplicity is a seasoning called a sincere heart. That is what impresses the people who eat it. That is special.

Regarding the essence of temple food, some gastronomy “experts” outside the Buddhist community have voiced criticism saying, “I find no difference between temple food and everyday Korean food or food prepared for royalty. There is a strong tendency to view temple food as being more mysterious than it actually is.” If you think about it, there are some aspects to this criticism that can be accepted. Temple food is not something that requires special recipes. On the contrary, the main thing that differentiates temple food from secular food is the temple environment in which it is cooked, an environment that has evolved over centuries. Two aspects of this environment are the sincerity of those who make food and the mindset of the person who eats it, as well as emphasizing this mindset as much as possible. The Meal Verse recited before eating clearly reveals these characteristics.

“Where does this food come from? May I be worthy of receiving it.”

The attitude and philosophy toward food contained in this very short phrase is clearly evident in Unmunsa's kitchen, like a bowl of sujebi which is boiled and served in two hours with only essential ingredients in the side dishes to bring out the flavor, including fresh kimchi made from napa cabbage, seasoned cucumber and water parsley, braised kimchi, and ppak-ppak-jang. And each dish has just the right amount of seasoning, neither salty nor bland, to cause no discomfort to the eater. In order to maintain that level of purity, those in charge of meal preparation must maintain the mindset of “preparing food with sincerity” rather than just making it. There are also other considerations for the eater, including the size of the radish pieces, the hands used to wash the celery, and even the shape of the burdock leaves as they are neatly stacked and steamed. All of these steps can easily be transposed over images of a mother cooking for her children.

In reality, the attitude of those in charge of meal preparation is probably no different from that of one's mother, who personally delivered warm meals to her children as they sat on a warm ondol floor.

Unmunsa's temple food is full of hope for the newly ordained student nuns to be nourished without getting sick, so they can continue their daily studies and successfully complete the four-year course. That hope is also expressed in the hands of Ven. Seojun as she hands out the soup, and in her eyes that observe the nuns receiving it. The rapport formed within the monastic college between the student nuns and their caregivers is so special that it is rarely found in any other religion or society in the world.

There is also deep gratitude from the student nuns who receive the food and return to their seats in the refectory. Nuns who have just been ordained cannot participate in baru gongyang (formal monastic meal) because they have just entered the school and have not even practiced the meal ritual yet. Baru gongyang embodies the essence of temple food, but at its core is the relationship between the food and one's attitude toward life. Even if you don't eat from a baru (bowl), you can still have the attitude emphasized by baru gongyang. We see the spirit of “baru gongyang without baru” in each person who silently eats all the food given to them without leaving a single grain of rice, and in the student nuns who put down their spoons, close their eyes, and savor the taste of the food. I see the gratitude reflected in their faces. In 2024, the tradition of temple food is still alive and well in Unmunsa's kitchen.

Jeong Tae-gyeom is a travel writer who loves food, people, and culture. He is the CEO of Dreaming Workshop. He served as a team leader at Gonggam Media Holdings and as an editor at KTX Magazine . He currently works as a guest reporter for magazines, including Travi and Travel Newspaper. His Korean publications include Finding the Way in the Forest, Beautiful Forest, published by the Korea Forest Service, and Long-Established Stores, published by the Seoul Metropolitan Government.

Unmunsa Temple

+82-54-372-8800

http://www.unmunsa.or.kr