On the Way to Scoop Up the Moon

Holding a Gourd Equal to My Capacity

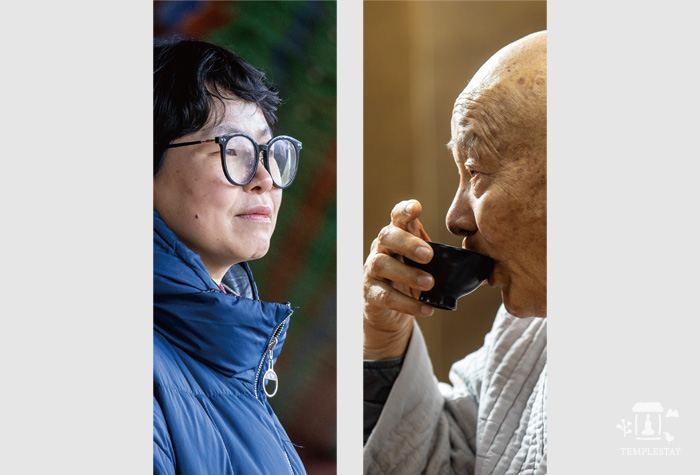

Ven. Seongpa, Supreme Patriarch of the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism

Text by. Baksa Photo by. Ha Ji-kwon

It is said that Tongdosa's “Jajangmae” plum tree is best viewed in spring, but it would not have attracted much attention if it grew in a plain field with only its red plum blossoms in full bloom. If it weren't for the elegant setting of a 1,000-year-old temple, would so many people have come to see its flowers? While listening to the exclamations and sounds of clicking cameras aimed at the last blooms of rain-soaked Jajangmae, I looked around the temple, the scene of all this magnificence. The temple is beautiful once again.

Certainly, there is no need to mention the beauty of the temple. The best artistic works of the past are here, having withstood the test of time, stripped of all superfluous elements. The temple is not a lifeless cultural property. It is a place inhabited by resident monastics and visited by many. Its beauty has many faces. The temple is experienced differently by people depending on their motivations for coming: those who come to enjoy the flowers once a year, those who come to pray, those who spend the night here and walk through the temple grounds at night and at dawn, and those who were born, live, and die here.

A Person Steeped in Cultural Assets

Ven. Seongpa says that monastics are “people who are born surrounded by cultural assets, live surrounded by cultural assets, and then leave.”

He further says, “I was born in a different place, but I entered monkhood at Tongdosa Temple. Then, I can say that as a monk I was born at Tongdosa Temple. I was born here and will stay here until I die. It is like napa cabbage thrown into the kimchi pot and the salt pot. What happens if a cabbage is tossed into a salt pot? It gets steeped in salt. It is naturally pickled.”

Passing through Tongdosa's buddha halls one by one, I reach Jeongbyeonjeon Hall deep in the temple compound, and sit across a table from Ven. Seongpa in a wide room. His comment about “getting pickled” is more understandable here. The room is Ven. Seongpa's personal gallery. Even its floor is unique. After applying natural lacquer, powder ground from mother-of-pearl was sprinkled to depict the Milky Way. The table placed on it and the paintings displayed on the walls are all his works.

Ven. Seongpa is a person whose bones are steeped in the beauty of cultural assets. At the same time, he is also a person who has admired that beauty to its fullest. Inheriting Korea's traditional Buddhist culture, he has explored various fields of art, including: natural dying, landscape painting, natural-lacquered folk painting, ceramics, hanji (traditional Korean paper), dancheong (decorative cosmic designs), architecture, taenghwa (Buddhist altar painting), and dry lacquer buddha statues. His artistic interest extends beyond just dabbling in one area to add it to his resume. He does not just learn from a teacher and replicate what he has learned. He has also rediscovered discontinued traditions and rebuilt the framework of artistic fields that were almost lost.

He made 3,000 ceramic buddhas to enshrine in the Hall of 3,000 Buddhas, and he built Janggyeonggak Hall to enshrine 160,000 ceramic plates which he fired, each containing content from the Tripitaka Koreana. In Japan he studied the “culture brought from Korea,” and then, went to China to study further. There he painted landscapes, and held a solo exhibition at the National Art Museum of China in Beijing, becoming the first Korean national to do so.

He also obtained a drone license because he wanted to paint from a bird’s eye view, looking down from up high.

There are no boundaries or limits in his life. Although he has studied and worked all his life, he always feels that he is lacking something. When I hear that he has interests in many fields with equal enthusiasm, I can only guess at his breadth of attention and interest.

Preparing "Tongdosa's Outdoor Reading Hall"

“Collecting Infinite Paper Books” is a project that provides a glimpse into Ven. Seongpa's perspective.

The foundation of Buddhist culture is much wider than we think, but when it comes to “publishing and printing,” Buddhism is all in, 100%.

Ven. Seongpa elaborates, “Before modern times and mechanization, the process of publication was different from today. Way back then, 100% of publishing and printing in Korea was done at temples, and it was not only Buddhist scriptures like the Diamond Sutra and Tripitaka Koreana that were published. Books like the Collected Writings of Toegye and the Genealogy of the Kim Clan from Andong were all printed at temples. Noblemen never did anything involving manual labor. They only provided the manuscript, and it was the temple monks who did everything else: copying the manuscript, trimming the wood for the printing plates, carving the content onto woodblocks, and the actual printing. Even the paper was made at the temple. The Great Dhāraṇī of the Pure Immaculate Light is the oldest printed book in the world. And metal-type printing was also done at temples. Jikji appeared much earlier than the Gutenberg Bible, making Koreans the first to use movable metal type.”

Books created this way were able to be passed down to this day thanks to the temples' efforts to preserve and protect documents. Ven. Seongpa's words have power: “The role that Buddhism played in our country's publishing and printing culture is not small; it is everything.”

He continued, "Nowadays, publishing and printing have changed a lot, allowing publications to appear quickly and in large quantities. Unlike the old days, the number of books is infinite. We have books from all over the world in Korea. People who studied in other countries brought books with them from those countries. So, if we try to preserve the world's book culture now, we can collect almost all the books from around the world. Even as I sit here, I can tell you that we have books from all over the world in our country. But they say some books are being discarded because there is no room in our libraries to store them."

This is why he started the “Collecting Infinite Paper Books” project.

He said, “It's really sad to see books being thrown away and discarded. If we don't do our part, nobody else will do it. There is no other organization doing this, and even if one philanthropist decides to collect a lot of books, there is no guarantee they will be kept and preserved for future generations. However, in a temple, everything is kept, even if resident monks and abbots move away. So, 80 to 90% of all cultural assets in our country are Buddhist in origin because they have been preserved well.”

His thoughts about books extend beyond a simple sense of duty. He believes books are also an alternative we can use to save our future. He said, “These days, people try to do everything quickly, but humans are bound to become overwhelmed if they keep that up. Just as a car engine overheats when it keeps running, the pain caused when people feel overwhelmed will only get worse in the future.” This is why he has such an interest in books. In order to prevent self-destruction by feeling overwhelmed, we must turn our attention to humanity's traditional and spiritual cultures, and books and reading are the only way to do that.

He explained, “That's why I collect books. When we practice and study in a Seon room, we are told to focus on the hwadu first. Even if delusions and defilements boil over and 84,000 afflictions arise, if you hold on to one hwadu, all of these distractions will vanish. But that's not possible for ordinary people. Reading is the same thing as holding on to a hwadu in a Seon room. Reading is something that can help you overcome an overwhelmed and/or derailed mental state. There will definitely be a time when reading will be needed.”

A Strong 'Back-up' for His Unlimited Collection of Books

“Tongdosa Temple has about 6 million pyeong (20 km2 / 5,000 acres) of land. The entire area is itself an outdoor reading hall. So, from now on, we need to make reading convenient whether one sits under a tree, on a boulder, or by a stream. We need to collect a lot of books, list them, and let people grab the books they want to read. Reading calms the mind.” I have often had some vague idea that temples could do much to help society in this age where society's mindset seems to be growing more and more shallow, but the idea of a 6 million-pyeong outdoor reading hall was beyond my imagination. He succinctly explained the role of the temple, citing a four-line poem.

A mountain spring spills forth clear water endlessly I offer this water to friends of the mountains Please bring a gourd container with you And scoop a full moon out of the spring

“In addition to drinking water… the poem asks readers to take the moon too, which is reflected on the water's surface. That's exactly what a temple does. A temple is a spring of ever-flowing water. So, to all who are thirsty, the poem asks them to come, quench their thirst, and take the moon also.”

The Master of Transformation Owns the World

As I look back on the path Ven. Seongpa has walked and as I listen to his words, I think about how much of the world one can experience. No matter what you have in mind, what kind of mindset should you have to go beyond your safety zone? What is the secret to his state of relaxation while doing so much?

Ven. Seongpa says his secret is “the freedom of seizing and releasing.” This means you must be able to grasp an experience but let go of it freely. And yet he describes himself as “a very greedy person.” Aren’t greedy people those who hold on tight and won’t let go? How is he able to let go of his experiences?

“Letting go is an act of even greater greed because even if I let it go, it’s still all mine.”

Indeed, it is worth adding the modifier “very” in front of “greedy.” If you are someone who thinks everything is yours, you will be free whether you hold it or let it go. At that point, wouldn't the distinction between what's mine and what's yours be meaningless? Even if we can't reach that level of understanding, I thought it might be a skill that could be helpful to us ordinary people, who always say we're busy. Then, I asked him the secret to being able to freely hold and let go.

“Well, regular monastic training won’t do it. Just knowing is not enough; it requires a lot of training and experience.

If it was something you could gain from knowing, you could understand it all through logic. But when situations arise, it won't work. Why? You have to learn from experience. It's like being in the Buddha's palm. No matter how far you run, you're still in the Buddha's palm.

So, you have to have the strength to bring things back whenever you want. If you catch a fish with your hands and drop it, you won't be able to catch it again. However, if it is caught on a fishing line, even if you drop it, you can bring it back in. That's what's important. Even if you let something go, it has to be at a level where you can say you didn't let it go; then, even if it escapes from you, it can't get far. You can bring it back whenever you want.”

This may have been possible because the world embraced by Buddhism is so vast. Maybe that's why, no matter which direction the Buddha extends his hand, you are still in his palm. Religion, philosophy, culture, or any field is within Buddha's embrace.

“When you go to school, you study many subjects.

Buddhism covers all subjects: science, philosophy, humanities, biology, etc.”

As I listen to stories that cross a wide range of fields, I naturally feel that Ven. Seongpa is like a “fish” swimming freely in the wide sea of Buddhism. At the mention of fish, he laughs loudly.

“I can transform into anything, not just a fish. I can be a fish, a bird, I can become anything. In spiritual culture, anything is possible. If you have a body, it might be in the form of a dog or a cow. The human spirit can do anything. You can be a saint or a villain.

The mind is capricious and everything is possible.”

Isn't Ven. Seongpa's ability to transform the secret to being able to explore various fields without limiting himself? He was once the abbot and spiritual patriarch of Yeongchuk Chongnim Tongdosa Temple.

He once lived as a stranger traveling around on a bicycle in an unfamiliar country where Korean was not spoken, as a student studying abroad at a late age, as a farmer tending wild flowers and tea fields, as a painter, a poet, and a craftsman. And at another time, he is the highest-ranking elder of the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism and served as its supreme patriarch. And throughout all these experiences, he remained the perfect, innocently smiling monk.

He is scheduled to have a solo exhibition at the Seoul Arts Center’s Hangaram Art Museum for a month and a half starting September 25th this year. It will be a rare opportunity to see works selected from among his 10,000 works. It is said that the focus will mainly be on unpublished works. Works he collected without giving them away or selling them—while calling himself an “evil person”—will finally see the light of day. I have seen a few of his works at Jeongbyeonjeon Hall and Seounam Hermitage, but I wonder if I can get a glimpse of his broader vision when I see them carefully arranged in the spacious art museum. I will take my too small gourd with me to scoop up my share of the moon.

Note

1) If you want a closer look into Ven. Seongpa's life, please refer to the book Working and Studying, Studying and Working (Narrated by Ven. Seongpa and written by Kim Han-su).

2) The poem Ven. Seongpa delivers is by Kim Nogyeong, the father of Kim Jeong-hui (aka. Chusa).

It is known that the poem was inspired by Kim No-gyeong's visit to Iljiam Hermitage where Master Choui once resided. Kim No-gyeong heard that his son respected Master Choui.

Baksa is a book columnist and famous as a “Buddhism geek.”She has introduced others to books and culture through various media including broadcasts and daily newspapers, and has interacted with the public through programs including “Book Listening Night” and “Book Listening Evening.” Her Korean publications include: To Me, Travel, and If You Could Smile Even if Your Chicken Had Only One Leg.

Tongdosa Temple

+82-55-382-7182

www.tongdosa.or.kr