Where Does Our Food Come From?

Time to Reflect on the Significance of “Roots”

Yeongworam Hermitage in Jangsu

Text by. Jeong Tae-gyeom Photo by. Ha Ji-kwon

Winter is a harsh season. Nevertheless, life goes on, and we must eat to sustain life. Eating, drinking, and enduring the wait for the new spring is the fate of all beings who survive the winter. The precious food source we rely on in this barren season is root vegetables. They are the source of life that also give temple residents the strength to survive the bleak winter.

A Relationship Rekindled in a Remote Place

It was a long-awaited reunion. The last time I met Jeonghyo Seunim was in the fall of 2018. We occasionally spoke on the phone, but due to the Covid pandemic, the trajectories of our lives did not intersect for a while. Our continued relationship under such adverse circumstance is something to be thankful for, and that’s why I decided it was time to see her again. Since we last met, she had moved from Yunpiram Hermitage in Mungyeong to Yeongworam Hermitage in Jangsu, where she assumed the role of abbess. Jangsu was a part of Korea I had never set foot on. I had been to the nearby cities of Muju, Jinan, Namwon, and even Hamyang many times, but I had never had the chance to visit Jangsu. The word “mujinjang” is always used when talking about remote areas in Korea. It is a general term referring to the three regions of Muju, Jinan, and Jangsu. These three regions are considered “remote areas” of the Korean Peninsula, no less remote than the deep mountain villages of Gangwon-do. Muju and Jinan are quite often mentioned as travel destinations, but Jangsu is not. The area is not well known, and not many people travel there, including myself. Perhaps that was why I felt excited on my way to Yeongworam Hermitage.

My first impression of Jangsu was peaceful, just like the countryside I saw as a child where smoke rose from every house when it was time to cook rice, and the savory smell of rice hovered over the fields. I passed through the middle of the village, which was far from the center of Jangsu-gun, and drove up a winding mountain path. I arrived at Yeongworam Hermitage, which consisted of one dharma hall, one dormitory, and one building used as a combination teahouse and dining hall. It was just as simple as one would expect a hermitage to be. This small hermitage sitting on the mountainside next to this peaceful village exuded quaint charm.

Jeonghyo Seunim had told me she had to make a trip between Jeonju and Iksan to take care of some business, so when I arrived, she was not there. I had arrived at the hermitage around dusk, and was getting used to the dark when she arrived. I felt a unique presence from the moment she appeared busting out laughing again and again. Even though it had been years since I last saw her, she greeted me as if we had just met yesterday. I was just starting to feel tired, but she woke my spirit up instantly, indicating what a strong relationship we had. As if the length of time we’d been apart didn’t matter, our relationship was rekindled anew in this unfamiliar part of Korea. She manages this small hermitage alone but is as lively as ever. I loved it. She was exactly the way I remembered her, and I slept comfortably in the room on one side of the teahouse. The night passed, and I felt as though the warmth I had long forgotten warmly embraced me.

Working in a Temple Kitchen Builds Wisdom and Virtue

As the winter gets colder, we often encounter a cool, damp morning mist. And in places close to a body of water, this mist rises from the water around sunrise. In the village in front of Yeongworam Hermitage, there is no large body of water, but a gentle damp mist flowed like clouds between the mountains. After being intoxicated by its beauty for a moment, I went to the dining hall, where Jeonghyo Seunim soon began cooking.

“What will you make for me today?” I asked.

“Wouldn’t yukgeuntang (stew of six root veggies) be good in the winter? That’s what I make best.”

Her hands were fast. She deftly trimmed and cut everything crisply all by herself, and the six root vegetables (burdock, lotus root, carrots, potatoes, taro, and white radish) were soon ready to be transformed into food. All of these ingredients taste best in the fall, but they can also be harvested and stored for quite a while. Jeonghyo Seunim began her monastic path at Bohyeonam Hermitage of Haeinsa Temple, where the recipe for yukgeuntang has been passed down from generation to generation. She has made it countless times to offer to the monastics there, and even after leaving Bohyeonam Hermitage, she still makes it every winter. It is her signature dish that she can make with her eyes closed. Jeonghyo Seunim is the one who introduced yukgeuntang to the world, and even now, many people think of her when they discuss it. That day I would taste this dish again. I wandered around the kitchen to see if I could help out in some way, but I just don’t have the skill to keep up with her when it comes to preparing ingredients.

“If you assume the responsibility of cooking for a long time, you learn a lot. These days, even as a postulant, one is rarely assigned to work in the kitchen, but in the past, it was essential. Even though it is difficult keeping your hands in cold water for hours at a time preparing ingredients, you naturally learn why you have to do it and cultivate the proper mindset. The senior nuns often told me that if you work as a chaegong (one in charge of veggies), you gain wisdom, and if you work as a gongyangju (kitchen master), you build virtue. I think I finally understand that now.”

It was enjoyable to stand next to her and prepare food while chatting. There were many things to take note of. I passed the vegetables I had washed to her as I shared my thoughts and feelings, keeping my hands and mouth busy. When preparing food, one also has to consider the person who will eat it. There are times you have to focus on the cooking process with all your heart, but there are also situations like this one where you work together and share your feelings with each other. In any case, the best food is always seasoned with love. I fully believe that. And that belief has rarely disappointed me. Isn’t that because the excellence of a dish cannot be evaluated solely by its taste?

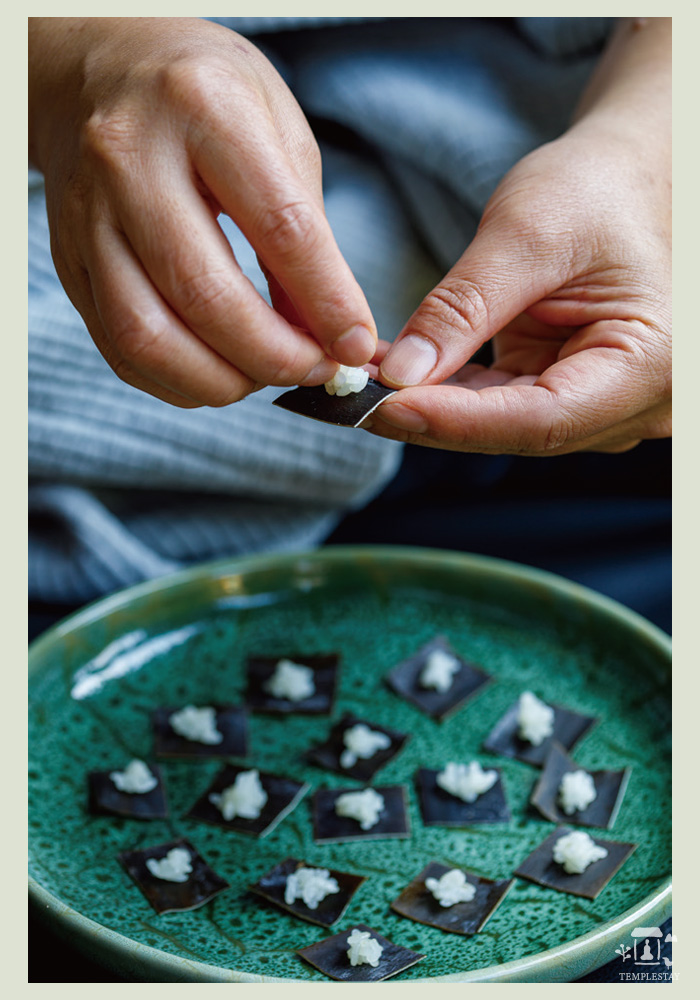

Just making yukgeuntang alone takes a lot of work and time, but Jeonghyo Seunim also started preparing braised chestnuts and kelp bugak. She said that a dharma sister in Gongju happened to send her some chestnuts, as she removed their outer shells and inner skins. I thought it would be better to eat chestnuts raw or to dry them well to bring out their subtle sweetness, but she preferred doing it her way. She even made kelp bugak in a way I had never seen before. She explained that putting two or three grains of steamed rice on the kelp, drying it for a few days, and then frying it would give it a different flavor. I often hear people say “It will be done in no time,” but that is never true. Things always take a little longer than “no time” but usually not much longer. We laughed together. As we worked, the morning sun rose brightly, and the mist hanging over the village dispersed.

Veggie Stock, a Canvas for Flavors

After braising the chestnuts in soy sauce, Jeonghyo Seunim put the prepared root vegetables in a cauldron outside the kitchen, sprinkled in some sesame oil, and began to stir-fry them. Stir-frying on a gas stove is okay, but yukgeuntang tastes best when made the old-fashioned way. It is the process of stir-frying at high heat over a wood fire for a long time that brings out the unique flavor of the vegetables. She then cut all the vegetables into bite-size pieces. There is something she realized in the process of preparing the ingredients. Whether or not something is pretty or not pretty is irrelevant. The value of life is not based on appearances. One thinks something that looks pretty will taste better, but that is not the case in reality. The essence of something lies in something that cannot be seen. Whether it is burdock or lotus root, there is meaning behind the care put into trimming it. When veggies are trimmed and cut well, their outer appearance is transformed.

When you stir-fry root vegetables in a cauldron, some produce a white fluid while others become sweeter.

Here, the important thing is to cook them in order, depending on whether they are hard or soft. Put the hard ones in first and stir-fry them for a long time, and then put the soft ones in when the time is right. This allows you to better regulate the texture. Then, add the veggie stock. She then stirred the boiling mixture briskly without stopping. While stirring, the smoke from the burning wood stung her eyes, but she kept stirring, just enduring the smoke.

The root vegetables were becoming tender, and the broth turned white. I asked her why she added the veggie stock.

“Why do you use veggie stock instead of plain water?”

“Veggie stock is like the canvas of flavors, and on this canvas, you add the natural flavors of the ingredients.”

Here, a question arose in my mind. If veggie stock improves taste, shouldn’t practitioners be wary of developing a craving for food that tastes good? Seen in that light, using veggie stock might impede one’s practice. In Balsim suhaeng jang (Awaken Your Mind to Practice), Wonhyo Seunim talks about the proper attitude toward food that practitioners should have.

When hungry, eat the fruit of a tree to comfort your stomach.

When thirsty, drink running water to quench your thirst.

―Excerpted from Balsim suhaeng jang

This is an attitude close to extreme asceticism. In the text that precedes and follows this passage, Wonhyo emphasizes that one should strive for a life of hardship. Furthermore, regarding the issue of eating, he says that one should only eat enough to stave off hunger and quench one’s thirst. This was his standard for the life of a practitioner. Regardless of that standard, is it right to use veggie stock to enhance the flavor of a practitioner’s food? Ven. Jeonghyo nodded her head.

She added, “It is also true that veggie stock should not be used. However, it is also true that from the perspective of preparing food for the community, a certain level of flavor must be maintained. Actually, there are no guidelines regarding the act of enhancing flavor. Therefore, the mindset of the one preparing the food must be considered, as well as the attitude of the person who eats it. To not develop a fondness for tasty food must depend on the mind of the person who eats it. Since I am the cook, I choose to use veggie stock.”

Food that Makes You Reflect on the Meaning of ‘Root’

Jeonghyo Seunim also voiced her concerns about enhancing flavor. One was the problem of using “tasty soy sauce (mat-ganjang)” when making temple food. As seasonings have become more diverse, soy sauce products have also become more specialized, and tasty soy sauce is very effective in adding flavor. This touches on the same issue of whether or not to use veggie stock, and she said she was worried about whether it was right to make temple food with such products. She also thought that all of this confusion was because there was no standard for defining flavor in temple food and how to view the act of enhancing flavor.

Even though no other seasonings were added except for well-fermented soy sauce and sesame oil, her yukgeuntang had a very savory flavor: the flavor that comes from root vegetables cooked with veggie stock. Therefore, even if you boil it in only plain water, yukgeuntang tastes good. Lastly, perilla powder was dissolved into the broth to complete the dish. This is the step that ties the flavors of each ingredient together. The flavors and textures of each root vegetable are their own, but the perilla powder combines these flavors in a harmonious way.

I put the yukgeuntang into my bowl and tasted it. The flavor was light and the broth rich. As vegetables ripen through summer and fall, their flavors intensify and condense in the roots. The reason root vegetables are eaten in winter is because they are the most nutritious at this time of year when there is nothing else to eat, and their flavor is at its best. In addition, when you factor in the cook’s concern and compassion for the diner, can there be any other seasoning as good?

The sweetness of the white radishes and carrots mingle together in this one bowl, yet each clearly retains its own essence. The ripened potatoes and lotus roots add to the flavor of the dish with their own unique textures. Lastly, the taro adds a subtle flavor. Waves of flavor filled my mouth one after another like a rising tide and then gradually dispersed. Finally, when those flavors subsided, the bitter taste of burdock provided a finale, without which the yukgeuntang would have had a much lighter taste. The salty sweetness of the soy sauce in which the chestnuts were braised lightly suppressed the lively texture of the chestnuts, a side dish that went well with yukgeuntang. Ven. Jeonghyo’s kelp bugak didn’t have any special seasoning, but its savory flavor exploded in my mouth the moment I bit into it. The taste was both familiar and unfamiliar at the same tie. The taste of the kelp, which was cooked by adding grains of rice instead of the usual starch or rice flour paste, was different.

I savored the food she had served me and felt somehow moved by it. I couldn’t help but feel once again that food made with concern and compassion for others is more special. As time passed, I became immersed in other thoughts. The yukgeuntang we ate that winter day enlightened me somehow. The taste of root vegetables is significant beyond just their flavor. In the season when everything is in decline, roots—the source of life—sacrifice everything to sustain us. I felt grateful and joined my palms together with true sincerity. Maybe winter is the season to contemplate the significance of roots and absorb the teachings they convey.

Jeong Tae-gyeomis a travel writer who loves food, people, and culture. He is the CEO of Dreaming Workshop. He served as a team leader at Gonggam Media Holdings and as an editor at KTX Magazine. He currently works as a guest reporter for magazines, including Travi and Travel Newspaper . His Korean publications include Finding the Way in the Forest, Beautiful Forest, published by the Korea Forest Service, and Long-Established Stores , published by the Seoul Metropolitan Government.