In the spring of 1905,

over a thousand Koreans

departed Jemulpo Port for Mexico.

They chose to pursue

the adventure of their lives after seeing newspaper

advertisements that promised they could “make big

money overseas.”

Their destination was the port of

Mérida on the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico.

However,

the ads in the newspaper were blatant lies.

What

awaited them were henequen (a species of agave) farms

spread out under the blazing Mexican sun,

tyrannical

farm owners, and hard labor from dawn to dusk.

But the

Koreans were tough and resilient.

Despite their poverty,

they helped raise funds for the Korean independence

movement and sent it home to Korea.

With dignity, they

overcame all kinds of discrimination and put down roots.

In the summer of 2025,

the 120th anniversary of this

Korean immigration to Mexico,

13 descendants—who

still had great respect for their ancestors—retraced their

ancestors’ footsteps to visit Korea.

At Beopjusa Temple,

they experienced the beauty and affection of Korea,

and

felt the Buddha’s teachings with their whole being.

Beopjusa Temple (“temple where the Buddha’s teachings reside”) is the most prominent temple on Chungbuk Province’s Mt. Songnisan (“mountain that has left the secular world”). It is a sacred site dedicated to Maitreya and where many people have relied on the buddhas and bodhisattvas and found hope in life. It is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Korean-Mexican youths who visited their ancestral home at the invitation of the Cultural Corps of Korean Buddhism (Director Mandang Seunim) arrived at Beopjusa Temple in the late afternoon, after 3pm.

These 13 young people flew all the way from Mexico to Korea, but not for just a simple visit. Their visit was part of the “2025 Invitational Fam Tour for Descendants of Independence Activists in Mexico” held by the Corps from June 9 to 15 to commemorate the 80th anniversary of Korean liberation and the 120th anniversary of this Korean immigration to Mexico.

Their amazement at visiting their ancestral homeland for the first time was clearly evident as they drank the plum tea offered by Deogwon Seunim, Templestay guiding nun at Beopjusa Temple.

After unpacking their belongings in Jeongjaedang Hall, the lodging styled in hanok (Korean traditional house), Choe Jaeseung, the Templestay team leader, taught the participants temple etiquette and how to properly offer three prostrations. Then they set out to explore the temple compound, led by Deogwon Seunim. Everyone’s eyes widened as they passed through Geumgangmun Gate and stood in front of the largest Maitreya Buddha statue in East Asia, standing 33 meters tall. The majestic and ancient appearance of Palsangjeon Hall, the only five-story wooden pagoda in Korea, and Deogwon Seunim’s explanation that the building is over 400 years old made it hard to resume walking. After thoroughly looking around Palsangjeon’s interior, they moved on to see the Twin Lion Stone Lantern, a designated national treasure and a uniquely styled structure created by Silla craftsmen. The shutters of their cellphone cameras clicked nonstop as if they didn’t want to miss a single thing. As most of them were visiting Korea for the first time, they probably wanted to show these pictures to their families back in Mexico.

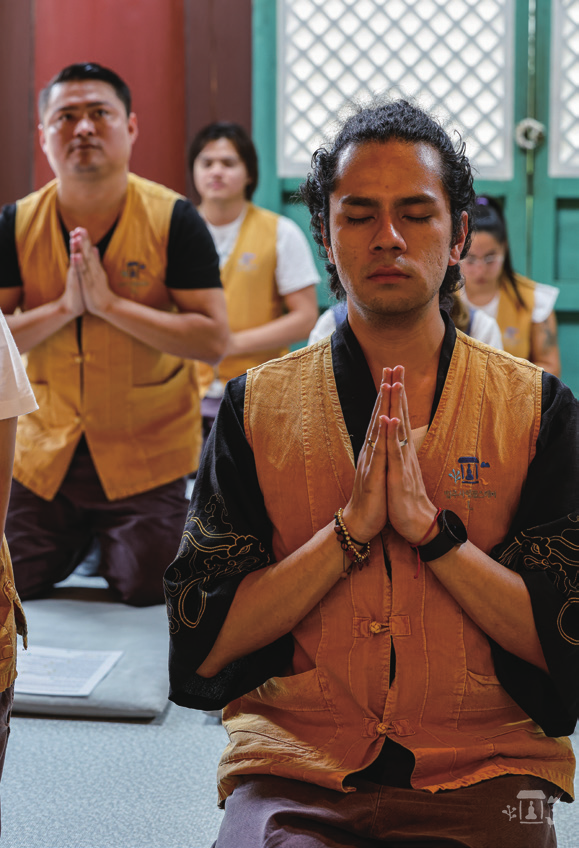

Finally, upon entering Daeungbojeon Hall, the main buddha hall, the visitors expressed more exclamations of admiration

The buddha triad enshrined there (a designated general treasure) was majestic, and the surrounding sculptures and dancheong (decorative cosmic designs) were mysterious to them. After practicing three prostrations to offer to the Buddha, the temple—unfamiliar to those born and raised in Mexico—gradually seemed less foreign. I carefully examined the faces of those wearing Templestay uniforms, watching them smile and putting their palms together, and I was overcome with an inexplicable emotion. I thought, “Ah! Korean blood flows through their veins! They have come a long way after a long wait!”

After nourishing their bodies and minds with temple food made with sincerity and devotion in the refectory, the sound of the Dharma drum announced the start of the evening Buddhist ceremony. The young visitors seemed enchanted as they watched the monks taking turns beating the giant Dharma drum, its magnificent sound permeating their bodies. It was a sound their ancestors may have heard countless times before leaving their homeland.

After the evening Buddhist ceremony was offered with true devotion, a program to teach them how to paint dancheong was announced. As each person carefully moved their brush with the colors they chose, their hearts seemed to naturally come together. Even though the designs were the same, the results were diverse, and the first day ended with them creating 13 works expressing each one’s individuality.

The next morning, at 4:30 am, the morning Buddhist ceremony began. The participants’ prostrations seemed more natural than they did at the evening Buddhist ceremony the day before. After the ceremony, a program to teach them how to string together 108 prayer beads immediately followed. They had had difficulty doing even three prostrations before, and now they had to string prayer beads one by one after each of 108 prostrations. Some emptied their minds first, while others thought of their families. The string of 108 prayer beads they made that day remained carefully wrapped around their wrists for the remainder of their time in Korea.

Upon leaving Daeungbojeon Hall, their legs were shaking from the prostrations, but after filling their stomachs with a hearty morning meal offering, they felt refreshed as if nothing had happened. All 13 of them volunteered to climb Sujeongbong Peak, a purely voluntary activity. Although only about 565 meters high, Sujeongbong is one of eight peaks on Mt. Songnisan and offers a panoramic view of Beopjusa Temple. The hiking trail was quite steep, and they climbed up the formation called “turtle rock” near the summit, holding and pushing each other on. They had not been close until they left Mexico two days ago, but now they seemed like a family.

After finishing the hike, Deogwon Seunim served them cool tea and gave each a small pouch containing the string of 108 prayer beads that they had made. The pouches had been completed by staff members using a traditional Korean knot. She also gave them a tumbler and a small bell to symbolize the awakening of wisdom. They ended their Templestay by learning a simple meditation technique to help them control their thoughts anytime, anywhere.

Korea has long considered filial piety an important virtue, but how many people remember their 5th, 4th, or 3rd great-grandfathers and grandmothers? There are probably not many families that can pass on stories from generation to generation about the lives of their ancestors. However, the 4th and 5th generation descendants in Mexico still remember and are proud of their ancestors who founded the “Korean National Association, Mérida Regional Chapter, Mexico” in 1909 and helped finance the Korean autonomy and independence movement.

One participant, Maribel Diaz Guzman Zavala, began her story saying, “I was impressed by Beopjusa Temple, which has preserved its traditions for over a thousand years.” A descendant of independence activist Lee Yeong-sun, she admired the 108 prayer beads she had strung with great care and said, “It was so joyful and comforting to complete the prayer beads by doing a prostration after each bead.” She added with a smile, “I really want to give these prayer beads to my mother as a gift.”

Another participant, Cristina Son Yi Guzmán Cong—public relations officer for the Mexico City Korean Descendants Association—is a descendant of independence activists Go Hui-min and Gong Deok-yun. She said, “I was happy to be able to feel the peace of a thousand-year-old temple in the ‘now-independent homeland’ that my ancestors so desperately wanted to return to.” She added, “I want to give the completed prayer beads to my grandfather.” She further said, “I was moved to tears when I thought that this kind of tranquility and peace was exactly the kind of homeland our ancestors had dreamed of.”

Padme Angelique Estrada Bazán, a descendant of independence activist Go Hui-min, recalled her great-great-grandmother. She still shares stories with her own family about her, originally a resident of Jeju. Kimchi, noodles, pajeon (green onion pancakes), and bibimbap were foods her maternal grandmother often made for her. After having a meal offering at Beopjusa Temple, she smiled and said, “It felt like I was eating a home-cooked meal.”

Yuri Chang Lee, a descendant of independence activist Lee Sun-yeo, said, “As I walked through the temple, I thought of my ancestors who must have followed the Buddhist path.” He is a rare Buddhist in Mexico, a Catholic country. His father—the first exchange student between Korea and Mexico in 1967—married his mother, the granddaughter of Lee Sun-yeo, and settled in Mexico. His father often talked about Korean Buddhism, so Yuri Chang Lee had high expectations for this Templestay. The temple in Mexico City that he visits with his family is small, so he was impressed by the grand scale and quiet atmosphere of Beopjusa Temple and was able to reflect on the Buddhist spirit of harmony and coexistence. He smiled as he said that he wanted to share his experience with his son when he returned home.

After their visit to Korea ended, our young visitors returned to Mexico and sent this email to the Cultural Corps of Korean Buddhism: “It was one of the greatest experiences in our lives to encounter our ancestors’ culture and rediscover Buddhism. We sincerely hope that this precious relationship will never be broken.”

It is often said that “all things teach the Buddha-dharma.” Since all things in the world are manifestations of buddhas and bodhisattvas, if you open your heart, you should be able to encounter buddhas at any time, even in Mexico across the Pacific. May the protection and wisdom of the buddhas and bodhisattvas of Beopjusa Temple illuminate their future.