Passing

It’s summer.

At lunchtime, I go to the forest.

At the entrance to the walking path,

I smell the scent of honeysuckle.

The scent from its white blossoms

is only perceptible within about three or four steps away.

After that, all one notices

is the scent of tangled grass

and the humming of the insects in the vegetation.

In those short three or four steps,

while still smelling the honeysuckle,

I think of people I once knew.

No matter how much the world has changed,

the fresh scent of honeysuckle cannot travel far,

and those who must part will part.

Those who cannot be seen cannot be seen.

The human heart does not evolve much in how it functions,

often showing no refinement.

This means that our yearnings always arise in a similar way,

in the same way that mixes with the scent of honeysuckle,

in a way that makes you

look into the distance

for no reason.

I first met him eight years ago, when I was a postulant. I heard that an important monk was coming from far away, so I put a fresh spring comforter in the guest room. In the afternoon, he arrived at the temple, as I had been notified. He was a novice monk who looked younger than me. He didn’t seem that important, but surely seemed to have come from afar. After I showed him to his room, he asked for a rag to clean it, so I gave him a couple. In the evening, I chose the tastiest Japanese red bean jelly and dorayaki we had removed from the altar that day and left them on the veranda outside his room, along with a few bottles of water. When I rang the bell at the third watch1 that night and passed by his room, I saw these items were gone and thought, “He must have eaten them.” His shoes were neatly arranged outside the door.

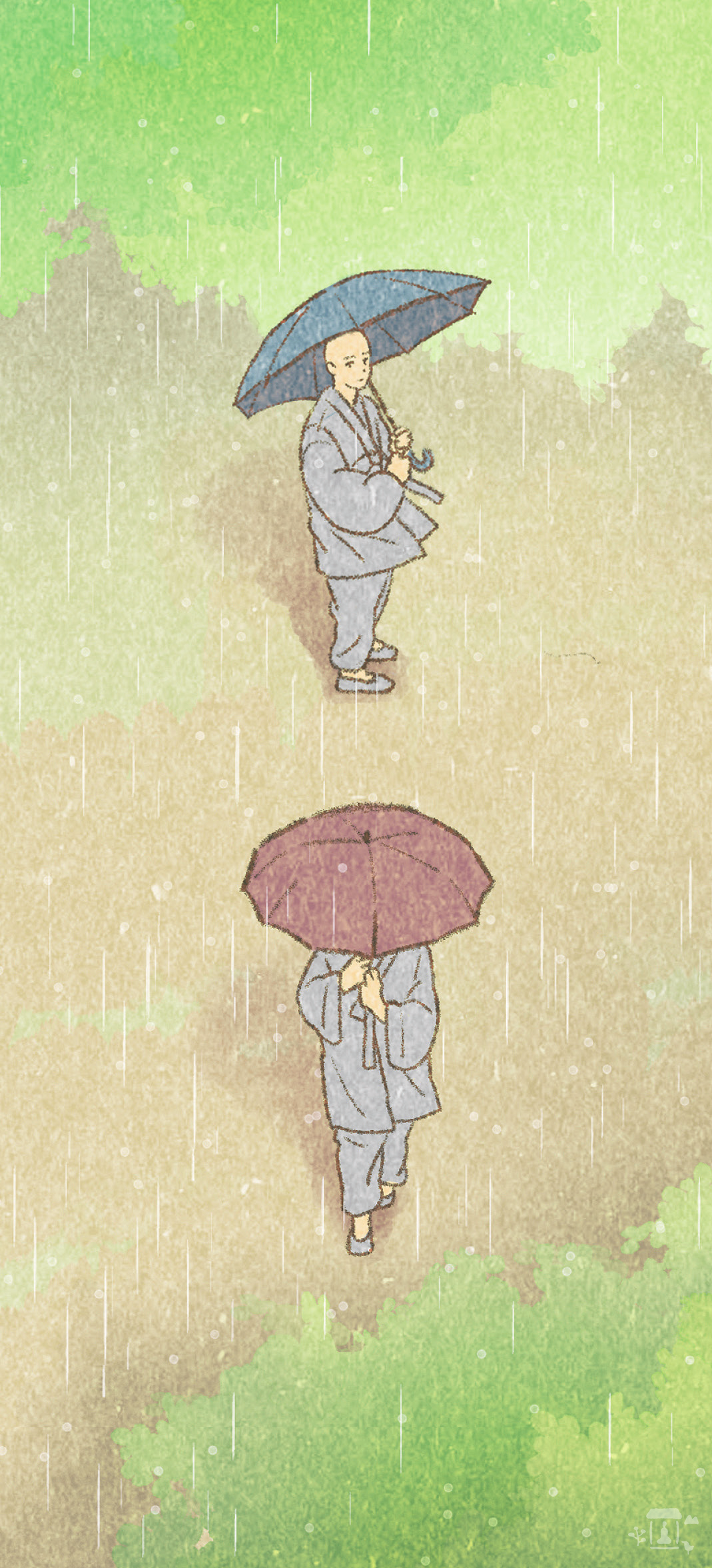

The next morning, it was drizzling. I was on my way back to the refectory after offering maji (rice offered to buddhas) at Gwaneumjeon Hall, and I was humming Lee Seunghun’s Rainy Street. The visiting monk was wearing a knapsack and coming toward Gwaneumjeon Hall from the other side. I gave him an umbrella, and we exchanged polite, meaningless greetings. When I looked back, he was walking up the stairs of Gwaneumjeon Hall and holding the umbrella. That day. Those greenish water drops. It was spring. The old Gwaneumjeon Hall suddenly felt new. The spring light that enveloped the long winter and subdued it, and the young, modest novice monk who passed by in front of Gwaneumjeon, which looked almost translucent in the spring rain. I was humming Rainy Street instead of chanting Buddhist mantra as I returned to the refectory. I can’t forget that day and those images for some reason.

Later, when spring was in full swing and the summer retreat season was approaching, the novice monk came to our temple’s monastic college. After finishing my postulancy that summer, I found that he and I were assigned to the same class in the fall, after which I had to see him every day for four years. We hated each other. There were times when I felt lost at the thought of having to be stuck with him every day when I returned to the monastic college after a short vacation. As a novice student in college, my days were tightly scheduled. Still, my rebellious nature showed through whenever it found an opportunity; my anger, my ugly, sleepy face, my hunger that was not easily appeased, my tears, my vulgarities… I brought up and exposed all of those faults without even trying to hide them. And he was the only person I could do that to without fear of being scolded or blamed, and I was the only person for him too. Sad. Fortunate. How precious.

We spent four years like this. There was nothing that was particularly funny or good in our relationship, just fighting, sleeping, running away, making mistakes, misunderstanding, understanding, and without any affection, but we developed a bond of sorts. Maybe he was a person who seemed to be just another side of me, so I was dissatisfied with everything he did. And eventually, I saw him as a pitiful family member, a new family member I gained after becoming a monk. Was it a mistake? A little bit. Sadly. But I want to say I came to see it as fortunate, even precious.

After graduating from monastic college, we resumed our separate lives. We contacted each other sparingly and saw each other occasionally. But we were still the same. We weren’t together, but at the same time we were. When I met him again at a Seon Hall the year before last, he and I were proper bhikkhus (fully ordained monks), but we recognized each other as being nothing more than immature student monks, not yet respectable Seon practitioners. During breaks from Seon practice, we would sneak in and out of the side door of the Seon Hall like young juvenile cats and go eat at a kimbap stand. But when the winter retreat season ended and summer came, he refused to eat kimbap anymore. His door was often locked. There were long days when he seemed to worry a lot. He then told me he planned to stop going to the Seon Hall for a while after summer and go on a long walking journey overseas. I responded to him indifferently, saying that if he didn’t have the heart to let go of his worries, his journey would be a futile act, just like keeping his door closed, and it wouldn’t matter even if he walked around the world several times. He had been quietly peeling peaches, but suddenly jumped up from his seat very angry.

On the last day of that summer, before going to the summer retreat’s closing ceremony, I stopped by his room for a moment. The room was completely empty, and I lay down next to him. He didn’t seem to mind when I deliberately picked my nose. I took out a bar of soap that I knew he liked from my pocket and tossed it on to his stomach before leaving. The scent floated in the air. And that was the end of it. Several months later, I received a text message saying he was doing well. The text was unusually long and rambling—unlike his usual self—and he said he would not return to the temple. He would keep that promise, but he would break his promise to see me again. I took this news calmer than I expected, but I don’t think my reply was as polite as it should have been.

The forest I walked through last winter feels completely different this summer. The familiar rocks that I previously used as landmarks are now covered in moss and are different colors. The piles of fallen leaves that were once abundant on each ridge have now flattened in the hot moisture, revealing new terrain. Water now flows through the previously arid valleys. The vegetation is particularly amazing. The tall grass now closes in on the path, and every tree branch sprouts leaves that cast shade on everything below. I was once proud about knowing the route before, but with the new seasonal changes creating variables, I am now unsure of the way. Then, I wander around helplessly and return to the temple.

But can change be called a variable? The coming of summer, the forest embracing summer. Meeting and parting. The end of one season and the arrival of another. Our visiting monk suddenly changed his path, and I remained on mine. Change is not a variable; it just is.

My mind keeps wandering during meditation, even though I know the terrain. When memories proliferate with my inhalations and exhalations, when unexpected memories spread like the scent of honeysuckle, at such times, meditation feels like summer. At such times my mind stays lost and helpless for days on end. Boring and cozy, distant days. But on a clear day, I wash my face in cold water and grope my way back to the point where I lost my way. Back into the forest and onto my meditation cushion. I calm my rapid breathing. I prepare. Instead of looking around, I decide to explore. A thin path stretches out into the thick forest. I perceive a single line, narrow and hidden, but not yet completely explored. Then, pushing through the longings growing in my mind and through my countless thoughts, I go forward. Forward. I pass the passing summer.