Dwell in Your Unwavering Mind

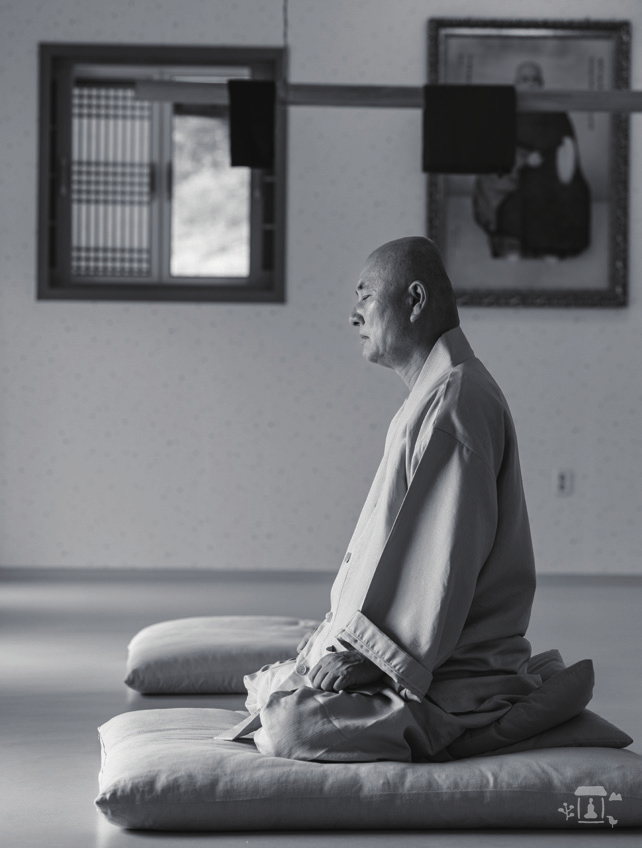

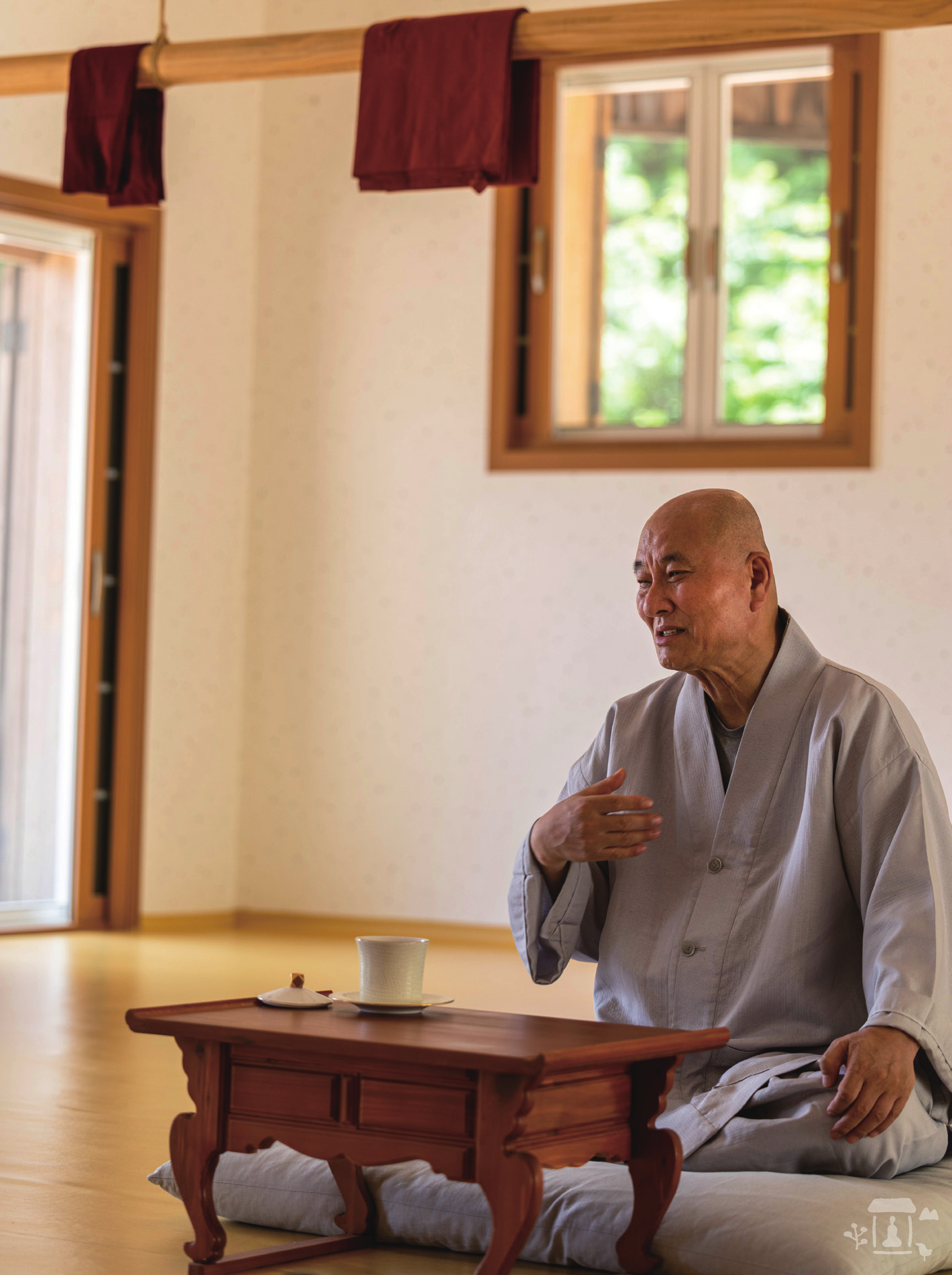

Woram Seunim, Spiritual Director of Yongseong Seon Center at Hansansa Temple in Mungyeong

“A temple with a twist, that’s Hansansa.”

When I said that, Woram Seunim smiled.

When I first arrived and saw this temple

surrounded by such tranquil mountains,

my first impression was that it appeared simple and cozy.

Where the main buddha hall would ordinarily be found at another temple,

Hansansa had a simple Seon room with a sign reading “Hyujeong Seonwon,”

which also served as its buddha hall.

“Hansansa was founded not long ago,

so it is not very complex.

It is just as simple as the surrounding nature.”

And as Woram Seunim said,

there was no decoration or embellishment.

Hansansa is the closest temple

to Baekdudaegan Mountain Range,

and it is located in a deep mountain valley

that requires a lot of determination to visit.

It is said to be a place

where slash-and-burn farmers used to live.

Despite its location,

nearly 50 people come here to meditate every month,

travelling four hours from Busan

or three hours from Seoul.

“I tell them not to come,

to go somewhere else for meditation,

but they are adamant about visiting here at least once a month.”

All the devotees who insist on coming here

have some long-term connection to this temple,

and they want to hear teachings from Woram Seunim.

With their presence,

tranquil Hansansa Temple is always full.

Early Ordination, Fighting Illness, and Crossing the Ocean to Meet a Master

Q: I heard that you entered monkhood in the 8th grade. This question may come across as a bit childish, but have you ever thought that it would have been better if you had become a monk later, after having lived among society, dated, and experienced what secular life is like?

A: I sometimes wonder about that. When I look back now, I think that if I had known the world a little more before I started monastic life, I would have made fewer mistakes in my practice and studies. It is a great advantage to become a monk early and start practicing right away, but I have also seen many cases where people are easily seduced by the temptations of the world because they did not know much about the ways of the world.

Q: Your writings are well received. I heard you loved literature when you were young. You could have become a writer or pursued another job. Do you have any regrets about that?

A: When I was in middle and high school, I won a lot of awards at literary competitions, so I think I had a talent. But upon entering monastic life, I spent my youth busy with practicing, studying, and serving the elders, which naturally prevented me from having opportunities to use my literary talents. I started writing books at a later age, and it’s been helpful. Some people consider writing to be really hard. I don’t think I’m that good at writing, but I just find it easy to do.

Q: I am so glad that you became a monk instead of a writer. Thanks to you, we can now understand the Buddha’s teachings more easily, and I am so grateful. I understand that you not only started monastic life at a tender age, but also practiced quite intensely, which probably led to you having a serious illness.

A: My body temperature rose to 40°C (104 F) and I almost died. Later, I found out that it was due to a combination of malnutrition, overwork, and other factors. The doctor declared after a while, “There is nothing I can do.” I was discharged after that, and the temple also moved me into a back room, thinking, “Oh my, a young monk is dying.” I eventually recovered somehow, but I had a difficult time. Later, sometime after I left military service, I got facial paralysis, which also upset me mentally. After recovering, I began the task of propagating Buddhism, and then I realized that my body was not completely recovered from the paralysis. I also realized that I had become a monk to practice the Way and attain enlightenment. I thought if I went to China, I would meet a hidden master and a doctor who could treat my paralysis. So, I just gave it all up and went to China. That was a big turning point.

Q: When you went to China, did you meet a master?

A: Upon my arrival, China was nearing the end of the Cultural Revolution, and Buddhism was in great decline. One of the greatest monks alive in the last days of the Republic of China was Master Xuyun (1840―1959), and his disciples were in their 60s, 70s, and 80s at the time. Some of them were unable to come forward and work because of the Communist regime, but they still had influence. Luckily, I arrived in China when there were still Seon (Chan/Zen) temples and lecture halls open all over the nation. They quietly continued the Seon lineage of Buddhism. I met some of the old monks and was very impressed by their unassuming, sincere attitude toward practice and life, and I can say that they taught me a lot. The slogan that Master Xuyun’s disciples expounded was “Humanistic Buddhism,” meaning “people are buddhas.” It is also the core teaching of Patriarchal Seon Buddhism. I was deeply moved by the way they quietly practiced Humanistic Buddhism, thinking, “This is the true spirit of a master or sage.” The reason I now advocate the idea of “Inbul (people are buddhas)” is because I was so greatly influenced by it. Seon Buddhism itself is based on the thoughts that “the mind is a buddha” and “a person is a buddha.”

Q: I think your experience meeting other practitioners while traveling around China was a great help to you.

A: It has had a huge impact on my life. China was having great difficulties 35 or 40 years ago. I was born in 1956, so I went through some really difficult times myself in Korea. And in the late 80s and early 90s, when Korea was starting to grow stronger, I went to China. And I found China to be like Korea was in the 50s and 60s, so I experienced difficult times twice in my life. At first, I was shocked. I had to face it all over again with my whole being. Cultivating the Way is not something you do only in your head; it is something you have to face with your whole being. Nowadays, people try to solve everything with their head, but that’s not all there is to it. The Way is something you have to face with your whole being. It’s something you have to cultivate with your whole being. That’s one thing I’ve learned well.

Q: The name of the practice community you lead is “Non-Duality Village.” I wonder if you named it that because you continually emphasize that things we tend to keep separate in our heads—life and practice, seeing one’s true inherent nature and benefiting sentient beings, wisdom and compassion, monastics and laity—are actually “not separate.” However, people today are constantly being forced to make choices, take sides, and fight each other by saying that others are either with us or against us. This is the cause of so much pain. Is there a way to apply the Buddha’s teachings to our lives right now?

A: The teaching of the Buddha is the non-dual Middle Way. This is the core of Buddhism. Our modern society has become seriously polarized as it has become more and more dominated by materialistic pursuits. It is not easy to fix this problem. Regarding the conflict between “left” and “right,” if we compare it to our body, it is like asking whether the right hand is correct or the left hand is correct. This is a question that cannot be answered if we only look at the hands. Resolution is only possible through the “transformation of perspectives.” If we sublimate it to the level of the body, then both the left and the right are necessary. In terms of the body, the right hand has its own work to do and the left hand has its own work to do. It is not that one side eliminates the other, but that there should be an integration of acknowledging both left and right. There is no choice but to transform one’s perspective. The Buddha’s teaching of non-duality and Middle Way is the best medicine in this era of extreme polarization.

Q: Is the reason we need to practice Seon in daily life to develop the power to see at a higher level?

A: The most essential elements of Seon are seeing things as they are and insight. What does it mean to see things as they are? It means seeing accurately, seeing correctly. It means seeing the truth as it is, without pretense. What is insight? It means seeing the whole. Insight means not seeing only the parts, but being able to see the parts as a whole, as one. That is the utility of Seon. If you see clearly, you can solve problems.

Q: When we usually talk about the benefits of Seon practice or meditation, we only talk about how it makes us feel “peaceful” or “calm,” but we rarely talk about how it actually solves life’s problems. However, as you said, if we see things as they are and have insight, there should be no conflict. Seon and meditation are ways to solve the serious problem of seeing everything only in dualistic terms.

A: Of course. People who misunderstand meditation think like this. If you have a bowl of water and the wind blows, it creates waves, and the water will become murky. If we calm the waves, the water will become clear again. That’s how we think of meditation. If you just think that meditation is just settling the murky water of stress (including concerns, worries)—which arises because the vessel of the body, the water of the mind, and the wind of situations exist—then your meditation will become futile. In order to meditate properly, when we encounter a situation, we must perceive it based on principles, and not just the situation itself. The Buddha said, “Your body is a temporary one created by causes and conditions. This so-called vessel is not something that inherently exists. The mind also is born and dies; it arises and ceases with one thought, so it has no inherent substance. Water also has no inherent existence. If there is no water of the mind, what could be shaken by bumping into a situation, and what muddy particles would arise?” Facing the fact that the five aggregates have no inherent existence is the proper way to meditate. Realize the truth that thoughts have no inherent substance, and then practice Seon and meditation. That’s it.

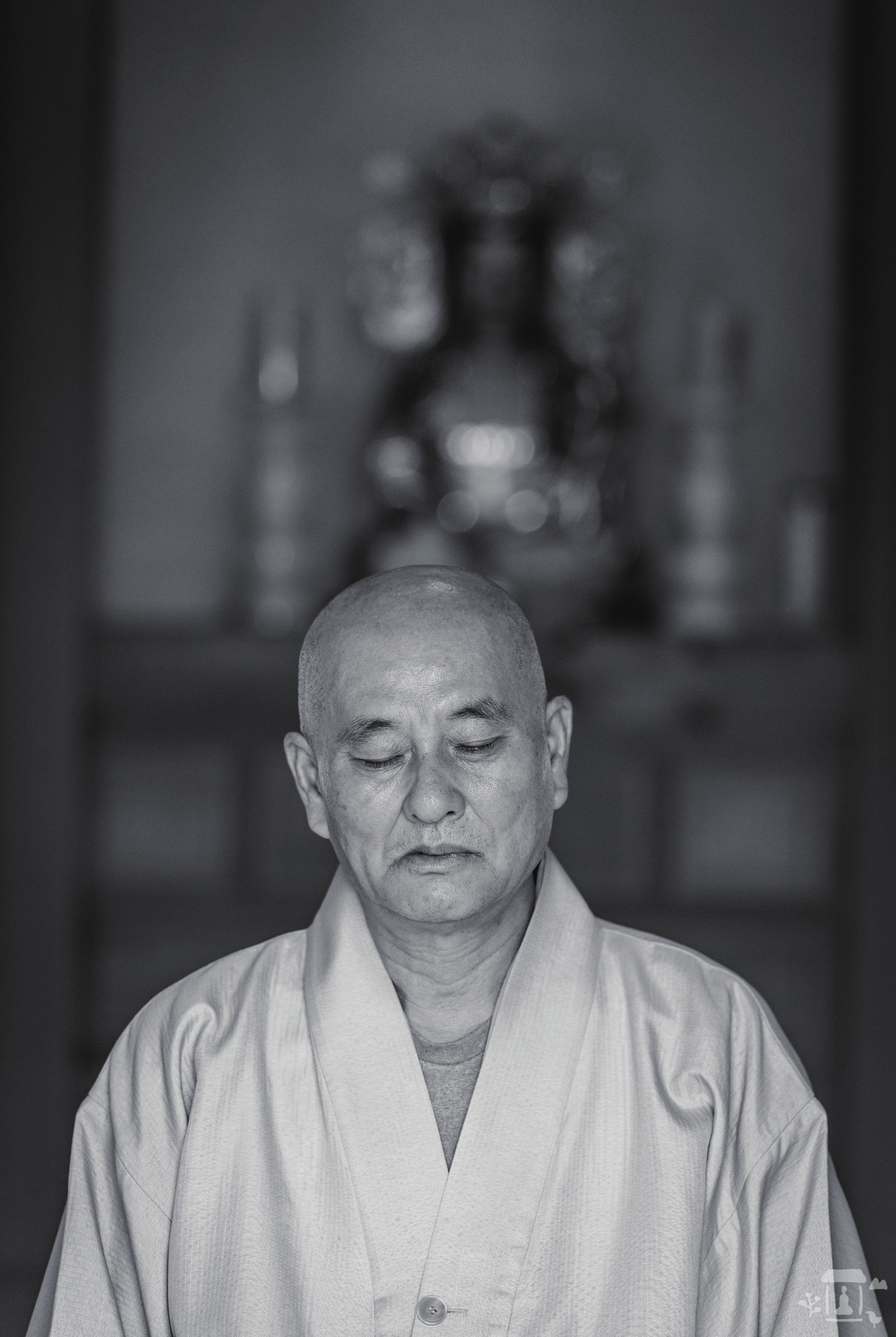

Q: I remember that in one of your Dharma talks, you said there are two minds: the mind that acts and the mind as imperturbable as a diamond. When people say their minds are in pain, that is the mind that acts. These days, people often talk about mental pain. How can we control or govern this mind that acts?

A: One mind is our “inherent mind” and the mind that acts is the “mind that arises.” The arising mind originates in our inherent mind. Comparing these to the ocean, the water itself is our inherent mind, and the waves that are in constant turmoil are the arising mind. The inherent mind is immortal and unchanging even if it has a thousand thoughts. Even if a thousand waves collide, the water doesn’t change; it remains water. If you realize that the waves themselves are water, you don’t need to be unnerved by them. The ocean consists of both water and waves; it doesn’t differentiate. You shouldn’t be fooled by the transient mind that arises and disappears. The arising mind is an illusion that constantly arises and disappears and it originates in the inherent mind. It’s like a bubble. If you think that bubble is all there is, you may experience suffering, joy, or sadness. But if you dwell in the inherent mind, which is the foundation, that is true Seon or meditation. The seat of true meditation is to dwell in the inherent mind. Just sitting on a cushion is not meditating. If you dwell in your inherent mind, even if suffering comes, you gain the power to see it objectively. If you dwell in your inherent true mind, external circumstance are only dreams. Even if you experience happiness or suffering in a dream, when you wake up, nothing has actually happened. To dwell in the inherent mind is to dwell in the place where you are truly aware, and not dreaming. In Seon, there is a lot of talk about “seeing one’s true nature and becoming a buddha.” This means to not only see all images, but also to see the absence of all images. Seeing one’s true nature is a verb, not a noun. Seeing one’s true nature is an action that must be practiced constantly. In this life, if you dwell in that place devoid of all images, even if you live among myriad images, that is seeing your true nature.

Q: You said, “Dwelling in a mind as imperturbable as a diamond is true meditation.” If you dwell in that place, you will realize that the mind that acts has no inherent substance and is just something that keeps arising and disappearing. Then, dwelling in that place of the unwavering mind must be the state of seeing one’s true nature.

A: That’s right. That is the state of seeing one’s true nature. Seeing one’s true nature must be constant in your life. It is not something that is acquired in a certain situation or mental state, but it must be achieved in daily life.