They say that being alone leads to loneliness.

But a genuine sense of loneliness always exists among people at some point in life.

The moment you compare yourself to others,

study others’ faces, and become conscious of others, that’s when you lose yourself.

However, time spent alone is different.

In the time we spend quietly confronting ourselves,

we finally regain confidence and learn the fullness of being alone.

There is a program where you can fully experience this quality time:

the “Attic Mumungwan Templestay” at Dorimsa Temple in Daegu.

Here, one enters a small attic, locks the door,

and looks only into oneself while doing Seon meditation.

In a space of about 3.3 m2 (about 36 square feet),

a journey to quietly rediscover oneself begins.

Dorimsa Temple, located in the heart of Dong-gu, Daegu City, at the foot of Mt. Palgongsan, is a monastery where mountain culture and urban culture coexist. It is a place where the teachings of Great Lineage Master Dorim Beopjeon (1925―2014) continue to inspire, and where the spirit of traditional Seon practice still lives and breathes. Dorim Beopjeon was nicknamed “Jeolgutong Practitioner” because, once he began Seon meditation, he did not move for three or four hours, “like a large stone mortar (jeolgutong).”

The Attic Mumungwan Templestay, planned and led by Abbot Jonghyeon Seunim, is offered here. Mumungwan refers to a space where one immerses oneself in intense practice while being cut off from the outside world, with the determination that “one will remain isolated from the world until one attains enlightenment.” It is a method that even Seon practitioner monks find difficult to choose, usually only choosing it after their training has matured to a certain extent.

The abbot has carefully reconstructed the spirit of traditional Mumungwan training—“not opening the door until one attains enlightenment”—so that people today can also experience it. This program attempts to break down the barriers between daily life and practice so that anyone can experience true and total silence.

“Break through the silver mountains and iron walls! Sit facing the wall!” This is the phrase used to describe the Attic Mumungwan program, a phrase introduced on the Dorimsa Templestay website. This program is held once a month in the attic above the abbot’s residence located in Saundang Hall. The attic space under the eaves—usually found in hanok—is divided into seven rooms, simply furnished, and each room is named for a different day of the week. Each participant enters a different room, locks the door, and immerses themselves in Seon meditation.

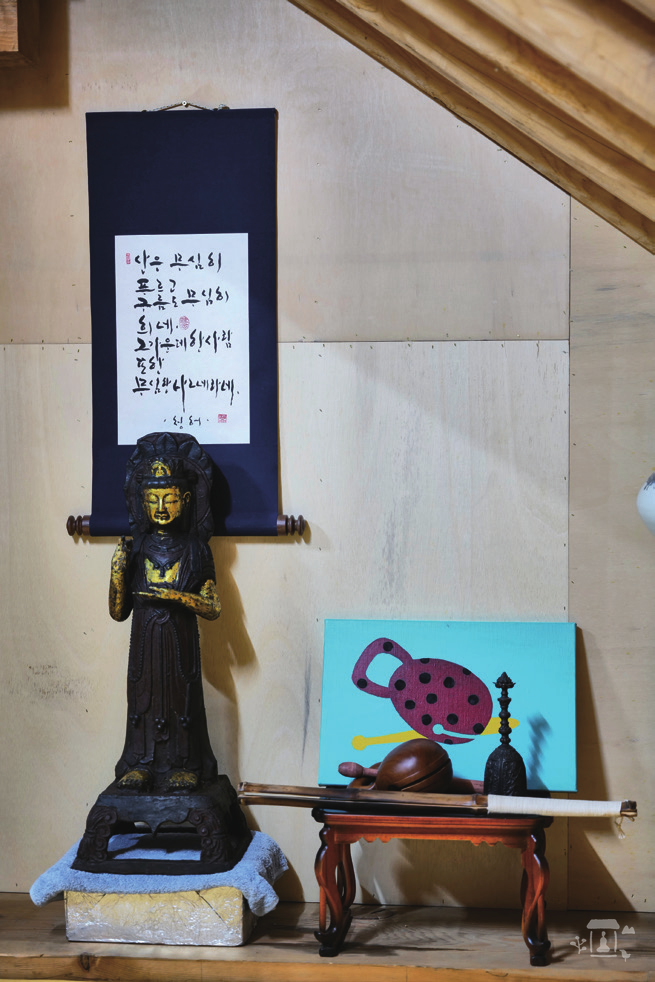

Each room is decorated in a unique way, adding a new sensibility to meditation. The Sunday room has a white porcelain moon jar, and the Monday room has a blue celadon jar. The Tuesday room has a bronze Avalokitesvara statue and a folding screen with 500 arhats covering the walls. The Wednesday room has a wooden Vairocana statue and a folding screen decorated with plum blossoms, and the Thursday room has old furniture and a mirror, encouraging one to face their inner self. The Friday and Saturday rooms each have a national treasure, a gilt-bronze pensive bodhisattva and a bronze pensive bodhisattva to welcome the Seon practitioner. Some rooms also have chairs for those who have difficulty sitting in the lotus position. The objects in each room are devices to help beginners—often challenged to just meditate on a hwadu—to immerse themselves in meditation more easily. This illustrates the abbot’s meticulous planning. The space itself becomes a vehicle to help one “face only oneself.”

“There are two meanings to Mumungwan practice. First, it refers to a gate that must be broken through, a reference to Zhaozhou’s famous hwadu ‘Mu (No).’ Secondly, it implies that actually ‘there is no door.’ Tomorrow, each of you will go into your assigned room, lock the door, and meditate alone inside. Before that, we will learn Ganhwa Seon by meditating on ‘Mu,’ just one of many gongans (koans).”

The abbot’s guidance lasts two days and one night. On the first day, participants go to the Seon room and learn Ganhwa Seon by contemplating the hwadu “Mu.” This is preparation for the next day when they enter the attic to begin Mumungwan practice. This short introduction and practice are characteristically tailored to beginners.

“Master Bodhidharma sat in meditation facing the wall. We will encounter many obstacles and walls in our lives, but the power to break down those walls starts with our meditation posture. Let’s start the first meditation by looking at the wall and concentrating on our breathing.”

The participants sat facing the wall under the Seunim’s guidance. They adjusted their postures and breathing to the sound of a bamboo clapper, signaling the beginning of meditation, and contemplated the question “What is Mu?” It is said that if you find ‘Mu,’ you can attain enlightenment, so all they meditated on was “Mu.” However, other distracting thoughts soon began to arise, inevitable for beginners. As the summer mountain breeze blowing from Mt. Palgongsan carried the sound of birds chirping, thoughts of “Mu” were replaced by thoughts of “birds.” Soon, they started to think, “What is meditation for?” and when the sound of the bamboo clapper signaled the end of their 20-minute meditation, it struck them like lightning. That was when they came back to Earth as if cold water had been poured on their backs.

Afterward, we walked around the Seon room to stretch our legs. The sky above Mt. Palgongsan was tinged red when viewed through the hanji paper window. The green grass and red roses growing against the wall showed off their summer finery by blending with the red sky. The moment I opened my eyes and faced the world after this short moment of silent meditation, I asked myself, “Is this kind of clarity created by my mind?”

After two sessions of meditation, we had a conversation over tea with the abbot. He praised us, saying, “If you were able to calm your delusions for even three minutes, you did a great job.” I nodded in agreement as he explained the reason for meditation while looking us in the eye. He said, “It may seem unthinkable to become a master through this short experience, but you were at least able to experience briefly how monks practice, the life they lead, and the culture of the temple.”

He continued, “Our life is child’s play. Our life changes depending on how we create, how we design, and how we proceed. This is the time when you become the main character in your own life and experience how to embellish your life as you wish. You come to know that ‘The mind creates reality.’”

“In the attic, you are free to sleep, lie down, or use your cell phone. Mumungwan is a practice where you become the main character. Practice is not something that someone forces you to do. Whatever you do, I won’t intervene. No one is watching. Just look into yourself in a comfortable position and with a tranquil mind.”

The next day, before entering Mumungwan, the abbot explained the rules to the participants gathered in Saundang Hall. One room per person with 20 minutes per room. Three 20-minute sessions in different rooms. You will find out which room you will be in upon entering the attic. Once you enter your room—where one person can barely lie down—and lock the door, your practice of facing the wall begins in silence.

After hearing all the explanations, it was time to go up to the attic. The sight of everyone climbing the stairs one by one reminded me of “entering the mountain” at a three-month practice retreat. Before entering the attic, all the participants gathered together and took a group picture. This was a ritual to consciously reflect on the determination to “not return until enlightenment.” Only then did the participants enter their rooms one by one. The moment I entered my room, I was alone, and my 20 minutes began.

Attics are place of stored memories. For some, it is a secret treasure vault where they keep books, comics, and secret diaries. For others, it is a cozy hideaway and playground. For those who never had an attic, the inside of a wardrobe was that small universe. Just like the attic of our youth, in this room today, we quietly enter our own world.

The participants sat down after closing the door to their respective rooms. When the door locked with a clang, there was only me in this space. In that silence, cut off from the outside world, an encounter with my true self began in silence, not in loneliness in the middle of a crowd.

After changing rooms three times and completing our three practice sessions, Abbot Jonghyeon Seunim served us tea. It was time for each of us to share our feelings. One participant in her 60s said with a smile, “I fell asleep because I was sleepy.” She then added, “I realized that happiness is something that you create in any possible way. Time passed really quickly while I was inside the room, and I suddenly asked myself, ‘How can I make this short time happier?’”

Another participant in his 30s said with a smile, “I felt emotions I didn’t want to feel, thoughts I had decided to let go of. However, after going into the room and spending time concentrating, I realized, ‘Properly facing and feeling these emotions right now is also a process.’ I’m glad I came.”

“I create the universe with my mind. The world that the mind creates has no boundaries. It is infinite. When you practice, the barriers that inhibit you are removed and the depth of your thoughts expands.”

The philosophy of this program is that you can face yourself only when you are alone, and that even a room measuring only three square meters can become a place to practice. While serving us fragrant tea, Jonghyeon Seunim told us quietly that practice is “a way to restore self-confidence.”

“Ultimately, it is my decision how to live my life. Will I live as the main character or will I live as a guest? If you are going to truly live, you should live as the main character.”

That is why Attic Mumungwan practice is not simply a place to spend time alone; it is a place to redesign one’s life. The first step to rediscover myself in silence and become the main character of my life. The starting point is here in this small, quiet room.

“We have been taught by our parents and teachers, but when it comes to truly important choices, no one can make them for us. In the end, I have to choose my life and take responsibility for it. Attic Mumungwan practice is a place to cultivate that kind of strength. Buddhist practice is the exercise of trying to reclaim my life. Everything comes from the mind.”