What is a “Waning Crescent”?

“Geumeum” refers to the last day of every lunar month.

The moon that rises around this time is called the “waning

crescent (“geumeum-dal”). The lunar cycle begins with

the waxing crescent, which gradually becomes rounder

until it becomes a full moon. Afterward, it gradually

becomes smaller and smaller until it becomes a waning

crescent, the smallest visible phase of the moon. In

addition, because it rises only briefly at dawn and soon

disappears, the night of the waning crescent is much

darker than other nights

Under a full moon, you can rely on the moonlight to walk at night, but on the last night of the lunar month, there is too little moonlight for this. How dark must the night be to say it is “pitch-black” or say “you can’t see an inch ahead of you?” Nowadays, there is no such thing as “last night of the month.” Electric lights are common in cities and in the countryside, and we now have flashlights, so we don’t have to wander around in the dark. Then, what were temples like before the advent of electricity and heating oil?

During the Joseon Dynasty, the standard time for morning prayers at temples was 3am. This tradition was maintained in mountain temples until the 1970s. As mentioned in Yaun Seunim’s Jagyeongmun (Statement of Self-admonition), monks did not sleep except during samgyeong (9pm to 3am), and they woke up at 3am to offer the morning Buddhist ceremony.

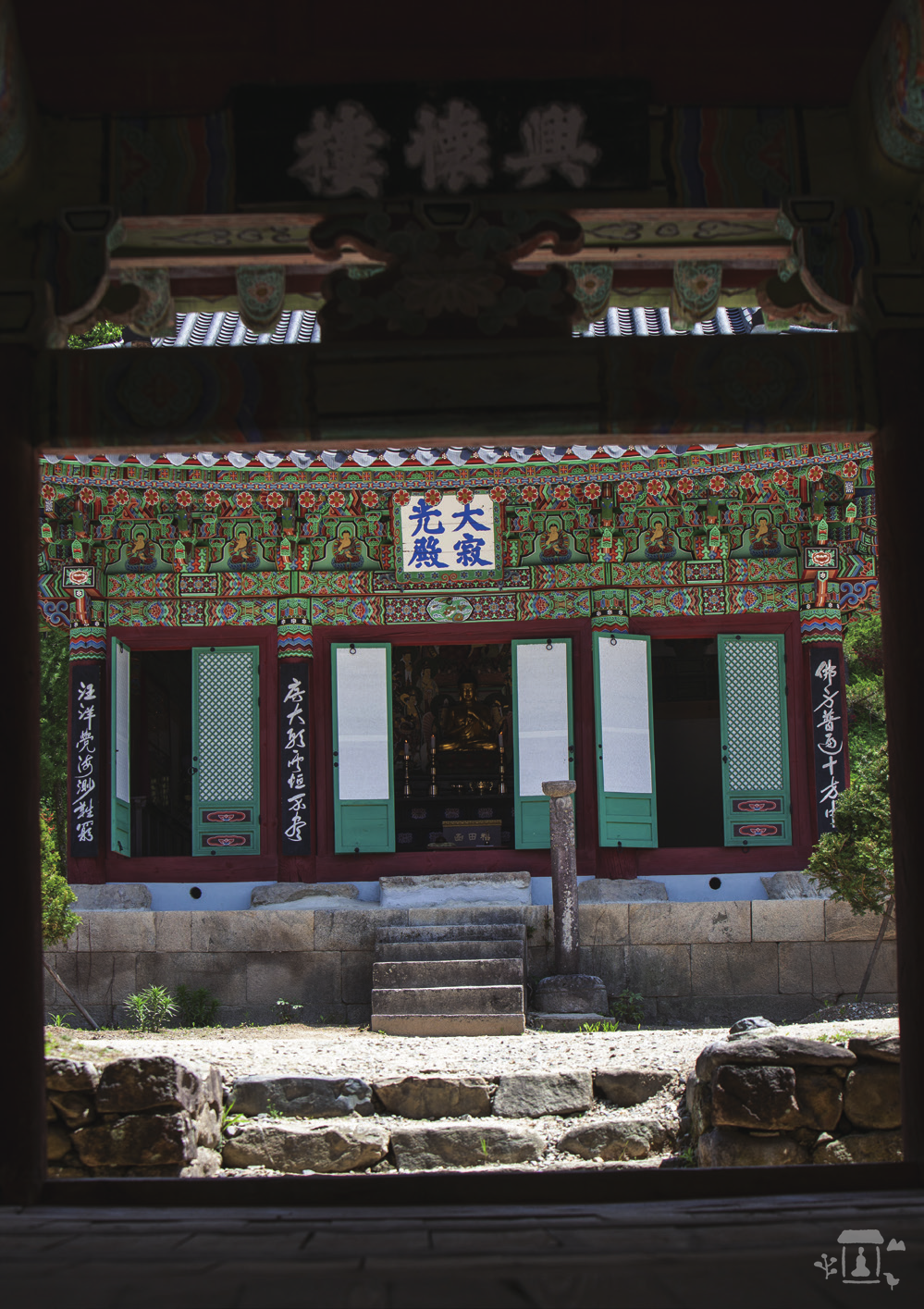

At 3am, it is still the middle of the night, especially on the last day of the lunar month. And when the cloud cover is thick, getting out of bed and going to the buddha hall must have been a commendable feat. The same goes for nighttime events. How can you move around when you can’t even see an inch in front of you? At a temple, lighting is needed to illuminate the courtyard and stairs. The temple’s stone lantern (“nojuseok”) was born out of this need. It probably got its name because it was a sort of “exposed stone pillar,” but in temples, it was also called noban-seokju, gwangmyeongdae, bururi, gwansoldae, and hwasaseok.

A nojuseok is basically a large stone slab placed on top of a stone pillar or post. It is a light source to light up the surroundings by burning gwansol, which is the red part of a pine tree around which pine resin has accumulated. When split open and lit, it burns for a very long time, so it was often used in these stone lamps

These nojuseok lanterns can be found in Haeinsa Temple in Hapcheon, Bongamsa and Gimnyongsa Temples in Mungyeong, Donghwasa Temple in Daegu, Beomeosa Temple in Busan, Okcheonsa Temple in Goseong, and Yongjusa Temple in Suwon. There are not many records of when these nojuseok lanterns were made. However, the stone pillar supporting the nojuseok at Daeseungsa Temple in Mungyeong has an inscription that reads “Year 7 of Yongzheng,” indicating it was built in 1729 (5th year of King Yeongjo’s reign). Because of this inscription, this nojuseok was designated a tangible cultural property of Gyeongsangbuk-do in 2008, and the term “nojuseok” became official.

Since hyanggyo (a local and public Confucian school) and seowon (Confucian academy) were places where many Confucian students and scholars gathered, they needed a way to light up the courtyard. Naturally, these schools adopted similar strategies and the “jeongnyodae” appeared. “Jeongnyodae” translates as “a platform that lights up the courtyard.” Since it also burned gwansol, it was also called a gwansoldae. Another term was “bururi (cage that holds fire).”

The first seowon of the Joseon era is believed to have been Sosu Seowon in Punggi, established in 1543 (38th year of King Jungjong’s reign). In front of its Jangseogak Hall stands a tall jeongnyodae, consisting of an octagonal pillar set in a hole dug out of natural rock. A pedestal with a taegeuk diagram was placed on top, and a thick octagonal slab was placed on top of that.

After the establishment of Sosu Seowon, numerous seowon were built nationwide. The more famous the seowon, the more students and visitors came, so a jeongnyodae to light up the courtyard was a necessity. Therefore, among the nine seowon now registered as UNESCO World Heritage sites, jeongnyodae can be found in seven of them: Sosu Seowon in Punggi; Dosan Seowon and Byeongsan Seowon in Andong, Oksan Seowon in Gyeongju, Dodong Seowon in Daegu, Namgye Seowon in Hamyang, and Donam Seowon in Nonsan. Jeongnyodae can also be found in hyanggyo, national educational institutions of the Joseon Dynasty. These include: Tongyeong Hyanggyo in Tongyeong, Danseong Hyanggyo in Sancheong, and Hongju Hyanggyo in Hongseong

There are also private homes where jeongnyodae still stand. One still proudly stands in the courtyard of the old house of the Gyeongju Choe Clan, the famous mansion of a wealthy noble family. This family most likely had many visitors, as it was a prestigious family that for nine generations produced nine jinsa (one who passed the primary state examination). And for 12 generations they maintained a manseokkun (land capable of producing 1,440 tons of rice every year). Therefore, this jeongnyodae must have been built quite a while ago, but it is said that it was rebuilt recently because the stone plate on top of it had been damaged. The stone plate on top of a jeongnyodae often cracked due to the heat from the burning gwansol. Another example of a jeongnyodae from late Joseon stands in front of Irodang Hall, the residence of Heungseon Daewongun in Unhyeongung Palace. Since there must have been many servants and visitors, a jeongnyodae to brighten the courtyard must have been essential.

In this way, jeongnyodae can be found in seowon, hyanggyo, and the homes of noblemen. In other words, whether it was a temple’s nojuseok or a private home’s jeongnyodae, it was a product of the times that brightened up a dark courtyard.

In 1876 (13th year of King Gojong’s reign), international trade began when Japan forced King Gojong to sign a treaty of peace and amity with Japan, and Western oil, the symbol of a new era, began to arrive in Korea. Before the introduction of Western oil, our ancestors used vegetable oils (castor oil and perilla oil), animal oils (fish oil and lard), and gwansol. The royal family used candles made from beeswax.

However, Western fuel oil burned much brighter and lasted longer, so after it was introduced, its popularity skyrocketed. In Hwang Hyeon’s (1855-1910) Maecheon Yarok, it is recorded that “one hop of oil can light up a night for three or four days.” And so, Western oil rapidly spread among the general public

In 1898, the first kerosene lamps were lit in downtown Seoul, and by the 1900s, Standard Oil and Texas Oil from the United States, and Shell Oil from the United Kingdom were competing for sales in Joseon. As kerosene became known nationwide, retailers appeared who carried barrels of kerosene to rural villages and sold it in small quantities, and temples could not help but be fascinated by the new kerosene lamps. Its brightness and longburning qualities were far superior to gwansol.

However, oil lamps could not be left out in the open. They needed something to block the wind and prevent them from being blown out. Glass was the latest cutting-edge material that had just arrived in Korea. Deungnongdae were crafted by erecting a wooden pole and fixing a glass fire chamber on top of it, in which the oil lamp could be placed and removed for refueling. How convenient it must have been to have lighting that could stay lit in the wind and rain!

If you look at the photos of temples in Joseon Gojeok Dobo, which began to be published in 1915, you can easily find wooden deungnongdae standing in the temple courtyards. That tells us how many oil deungnongdae were erected in temples all over the country. However, wooden deungnongdaes are not permanent, and there is always a risk of fire if the oil lamp breaks, so stone deungnongdae naturally appeared. By placing a stone slab on top of a tall stone pillar and fixing a glass chamber on it, you can put in and take out the oil lamp as needed. Very convenient! Oil lamps evolved into nampodeung, hand-carried lanterns with glass caps over the wicks. These became popular because they were easy to carry and could also be used indoors. The Japanese pronounced “lamp” as “nampo,” so Koreans added “deung (lit. light)” to make it “nampodeung.

However, stone deungnongdae later disappeared into the back alleys of history due to the advent of electricity. This is because electricity, which produces more light and is more convenient than oil lamps, was introduced to temples, and electric lighting replaced them.

When electricity was first introduced to temples, stone deungnongdaes were still useful because they could be wired for electric bulbs that could be turned on and off. However, as electric lights were hung on the eaves and installed on the ceilings of the buddha halls, there was no longer any need for outdoor lighting. Since electric lights were installed in each hall and the courtyards were no longer dark, there was no need for outdoor lighting

One temple that has preserved the tradition of using both nojuseok and stone deungnongdae in front of its buddha hall is Haeinsa Temple in Hapcheon. In front of Haeinsa’s Daejeokgwangjeon Hall stand one nojuseok and two stone deungnongdae, the latter sitting on stone pillars under the retaining wall of the buddha hall. There is another deungnongdae in front of Haeinsa’s Bell Pavilion. Moreover, the stone deungnongdaes in front of Daejeokgwangjeon Hall still have the electric wires that were originally installed. They have been disconnected but are still there, a lingering reminder of the switch from oil to electric deungnongdae.

Two temples that retain both the nojuseok and deungnongdae are Daeseungsa Temple in Mungyeong and Okcheonsa Temple in Goseong, Gyeongnam Province. One temple that only maintains one deungnongdae is Sutasa Temple in Hongcheon. There used to be a stone deungnongdae in front of Goundaeam Hall—where most eminent monks of the temple resided—at Gounsa Temple in Uiseong. As Gounsa Temple recently sustained damage in a forest fire, I don’t know if the deungnongdae survived.

Nojuseok and deungnongdae are relics that have a long history. For centuries they were crafted and maintained, but many have now disappeared into the dustbin of history. However, they were once new cultural innovations that provided an important convenience to the people of the time. Civilization has evolved and continues to evolve. If we preserve and record the history of such relics, the spirit of creating new things by emulating the old will be passed on.