Colors of a Mountain Temple

Text by. Lim Taek-su Illustration by. Kim Sang-gyu

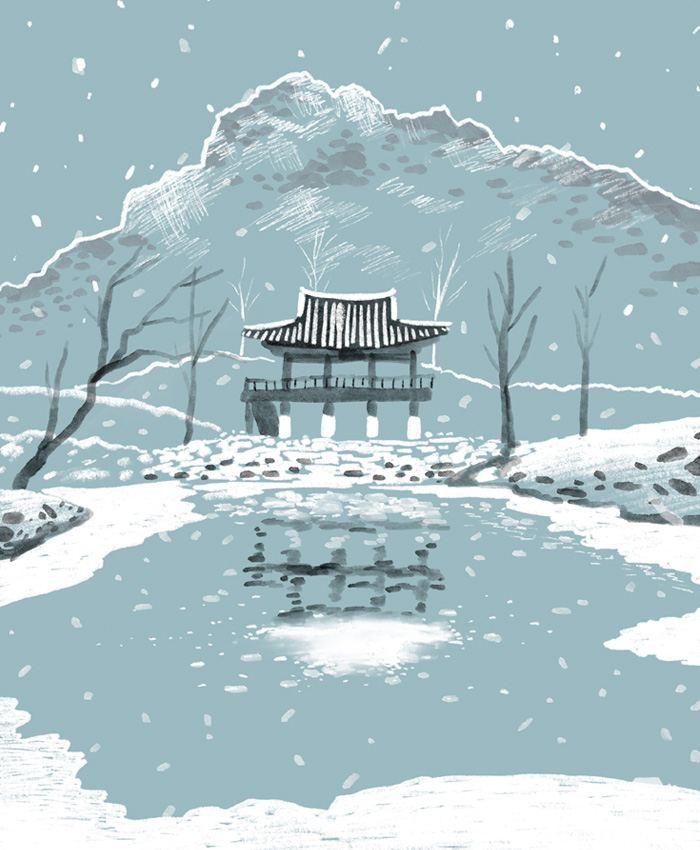

It is winter, the season of silence and meditation. The trees in the forest have also entered winter retreat like monastics, and the trees on top of the mountain once radiating a vibrant green are becoming thinner ahead of the trees lower down. All traces of the verdant spring, the abundant summer, and the ecstatic fall have been erased, and the forest is returning to the beginning, willingly waiting for the snow. This cannot be anything other than the harmonious cycle of the dharma.

As the nature surrounding the temple recedes like an old landscape photograph whose colors have faded, the colors of the dharma halls stand out. The faces of the Four Heavenly Kings with different facial coloring also catch the eye. In the Buddhist view of the universe, Mt. Sumeru sits at the center of the universe, and the Four Heavenly Kings are deities who guard the four cardinal directions while posted at the midriff of the mountain. Therefore, the first temple gate you encounter represents the one mind, through which one enters the buddha realm of non-discrimination, and the inner temple you reach after passing through the Gate of Heavenly Kings can be said to be the middle of Mt. Sumeru.

Usually, the Four Heavenly Kings have huge bodies, glaring eyes, and fierce expressions, and they hold swords, spears, dragons, and snakes in their hands, while trampling evil spirits under their feet. Therefore, even the lute played by the King of the East can be seen as a tool of punishment. The mission of the Four Heavenly Kings is to block evil from entering the temple and to subdue evil spirits. Furthermore, they are guardians who resolutely protect not only the space inside the temple compound but also the Three Jewels of Buddhism. I heard there is a temple that recently enshrined the Four Heavenly Kings depicted as handsome men. And another temple depicts the Four Heavenly Kings with cartoonish elements that children would like. It seems that these attempts are an effort by the temple to make the Four Heavenly Kings more approachable and relatable to those who visit the temple. They should radiate friendliness to encourage people to approach them and at least encourage visitors to read the information on these kings provided by the temple.

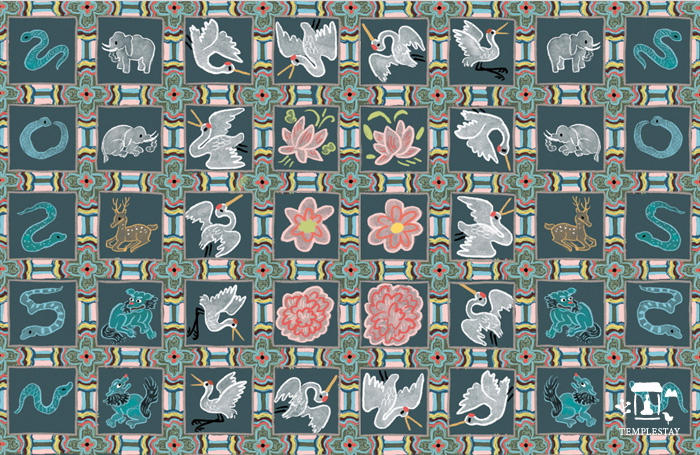

Above all, the delicate colors of the dancheong artistic cosmic designs that are the primary decorative feature of a temple catch our attention. Currently, the term “dancheong” is only used in Korea. In China, it is called “architectural painting,” and in Japan, it is called “architectural coloring.” The main purpose of dancheong is to symbolize the authority and hierarchy of a building, and in practical terms, it protects and preserves the wood and conceals the rustic exposed ends of the beams.

Traditionally, China mainly used red, and Japan used black and gray. Korea used the five cardinal colors (blue for the east, red for the south, yellow for the center, white for the west, and black for the north). These colors are based on the principle of yin-yang and the five elements. There are over 30 dancheong patterns, with the harmony of red and blue being most important. Yin and yang are not dichotomies with no connection; rather they constantly clash or influence each other to achieve harmony and balance.

Dancheong are classified according to the use and status of the building. Gachil Dancheong, the basic form of dancheong, involves applying a single color to the surface of the wood without any pattern. It was used on the Jongmyo Shrine and on Namhansanseong Palace. If a double line in black or white is applied to Gachil Dancheong along the borders of the painted surface, it is called Geutgi Dancheong, and was mainly used for shrines and auxiliary buildings. In Moro Dancheong, dancheong is applied to both ends of a beam or plank and the middle part is finished by drawing lines. It was mainly used on palaces and government buildings. In Geum Dancheong, the middle part of the Moro Dancheong is applied with a decorative pattern or special design. It was mainly used for Buddhist temples. Lastly, in Juchil Dancheong, white walls are painted red. Korea used this a lot during the Three Kingdoms period and the Goryeo Dynasty. This last tradition was transmitted to Japan from the Baekje Kingdom and became established as a Japanese style.

The coloring principle of Korean dancheong is green for the upper part and red for the lower part. This principle reflects the abundance of pine trees a characteristic of Korea which depicts harmony with nature in its designs. In addition, the lower part of the building, which gets a lot of sunlight, is painted red, while the upper part, which is darker due to the shadow of the eaves, is painted green and blue to increase brightness and create overall harmony.

The four colors symbolizing each of the Four Heavenly Kings and the colors of dancheong are both based on the five cardinal colors. In these five cardinal colors, there are regular colors corresponding to each cardinal direction and intermediate colors in between. The theory of the five elements combined with the five cardinal colors of dancheong is described in detail in the “Artificer's Record,” found in the Rites of Zhou. It is an attempt to mix colors through the concept of mutual supplementation and mutual restraint of the Five Elements theory and create countless shades within it. The use of neutral colors obtained through these intermediate colors became an essential element of dancheong.

When I think of a typical neutral color, gray immediately comes to mind. One day, a foreign Templestay participant asked me why monks wear gray. At that time, I gave a poor answer because I was only thinking of the neutral nature of gray. Later, when I asked a monk about it, he told me that gray symbolized the Middle Way. He said, “The visible world is mixed with the invisible one, and it is neither white nor black.” Gray is a mixture of black and white, and it symbolizes the middle way that leans neither toward black (which absorbs light) nor toward white (which reflects all light). Like a two-headed snake, it is similar yet different, different yet the same. This is probably why Nagarjuna said the Middle Way was “neither one nor two.”

In the Buddhist cultural sphere, Korea is the only country where monastics wear gray robes. The reason Chinese monks wear long robes which they do not wear in India was because of the cold weather and their aversion to exposure. In the course of accepting Buddhism, each country designed their own robes that were suitable for its climate. There was one problem when Korean monastics wore long robes. Article 60 of the monastic precepts stipulates that when a monastic receives new robes, they must dye them in three colors (blue, black, and a brownish color made from bark). So, monks dyed their robes black using dark earth, charcoal, or ink. Korean monks wore long black robes with a red gasa (kāṣāya) that came from China over their traditional clothes.

There is a reason why Korean monastics changed from black robes to gray. When you wear clothes dyed with charcoal or ink, at some point they start to look gray. Unlike today, back then it was difficult to prepare a set of robes, so most monks would have worn black robes until they faded to gray. With that in mind, the Bongamsa Practice Movement, aimed at reforming Korean Buddhism, had a decisive influence on wearing gray robes. Starting with the Bongamsa Practice Movement started to purify Korean Buddhism which had become corrupt and degenerated Seongcheol Seunim insisted on burning all black silk robes and wearing gray cotton robes. Accordingly, the Jogye Order, influenced by Seongcheol Seunim, established rules for wearing gray robes and standardized the color of monastic robes for Korean monks. However, there are many sects in Korean Buddhism, and each sect adopted a different form of monastic robe.

Due to the influence of Chinese Buddhism, Korean and Japanese monastics also wore black or blue robes. Some monks also wore blue-green or purple robes. If you look at the restored portrait of State Preceptor Gakjin, enshrined in the Great Hero Hall of Baekyangsa Temple, you can clearly see the different colors of monastic robes. He wears a red gasa over a blue jangsam. The jangsam is adorned with a black fringe, and the gasa has a gorgeous floral pattern, creating a unique look with a mix of peace and authority. If you look at the robes worn by generations of great monks enshrined in Jinyeonggak Hall, the gorgeous colors are in harmony without being flashy; they exude peace and a casual air of authority.

Just as there is the summer solstice (haji), there is the winter solstice (dongji). The symbolism of red (one of the five cardinal colors) is also well expressed in dongji patjuk, the red bean porridge made to celebrate the winter solstice. Dongji the 22nd of the 24 solar terms/periods—was called the Little New Year (ase) in the old days. It symbolized the resurrection of the sun after a long, dark night, so it was treated as the Little New Year, which had secondary importance after Seollal (the Lunar New Year). Therefore, there are sayings such as, “You only get a year older after dongji” or “You only get a year older after eating dongji patjuk.” When the red bean porridge was ready, the elders of old would first offer it to the ancestral shrine and hold a Dongji-gosa ceremony. They also shouted “Gosure” and sprinkled it inside and outside the house because they believed that the red color of the beans would drive away evil spirits. In addition, the “Gosure” ritual of making red bean porridge and sharing it with animals that were also short on food in the winter also reflects the Korean people’s spirit of living together. There was also a custom of “Dongji heonmal” where a daughter-in-law would make and offer padded socks to their elders beginning from the winter solstice until New Year’s Eve. The royal palace considered Seollal and dongji as the two most important feast days and held banquets. One record says the Gwansanggam the institution responsible for astronomy, geography, calendars, and rain measurement made a New Year’ s calendar and presented it to the king on dongji day.

Even now, temples distribute red bean porridge and new calendars to their devotees on this day.

The year 2025 is the Year of the Blue Snake (eulsa).

The name “eulsa” symbolizes the meeting of the energies of wood and fire, heralding new growth and change. In the five cardinal colors, blue symbolizes hope and new beginnings. Blue emphasizes flexibility and adaptability, including the energy of water, which means that we need to be flexible in the midst of many changes in 2025. In addition, the spiritual characteristics of the snake wisdom, resilience, change and regeneration imply that 2025 will be a time to shed the past and welcome a new beginning.

It is said that when a snake drinks water, it turns to poison, and when a cow drinks water, it turns to milk. This saying appears in Admonitions to Beginning Students (Gyechosim haginmun) by Jinul (1158―1210). It means that nothing in this world is immutably good or bad. Water can be both a medium for poison and milk. Water itself is not good or bad. There is a reason why snakes produce poison and cows produce milk. This is because of karmic associations that change form according to the situation.

Korean people have long believed that snakes are guardian deities that protect homes, and have made them objects of worship. In Buddhism, snakes are one manifestation of Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva, a bodhisattva who awakens ignorant people and lights the lamp of wisdom. Legend states that snakes came down to the complex and mysterious world of the living and became snake gods to experience the world of living beings. They have the nature of finding light and expanding knowledge in the lowest of places.

Sometimes, images of a snake biting its own tail are found in temple murals.

This represents rebirth and eternal life, or the infinite and cyclical nature of the universe, like the ancient symbol of the ouroboros. Also, when our ancestors saw snakes shedding their skin every year, they saw it as symbolizing immortality and rebirth. Therefore, it is often used as a symbol for hospitals, clinics, and medical organizations, both in ancient times and today. The symbol of a snake curling around a staff seen on ambulances represents Asclepius, the god of medicine in Greek mythology.

Most people have a universally negative perception of snakes, but the consciousness of life and wisdom that snakes possess are virtues we should cultivate. In the Snake Simile (Alagaddupama Sutta; MN 22), found in the Majjhima Nikāya, snakes are likened to the dharma in the Buddha’s teaching to monks. The dharma that is not properly examined and is misunderstood is like the poison of a snake. One of the characteristics of a snake is that they only look forward and do not look back, which should remind us to put in ceaseless effort to move forward in our Buddhist practice.

Kim Sang-gyu studied visual design at Seoul National University. He is interested in nature, the environment, folk tales, legends, and religion. Starting with his first picture book, Dari's Soul Bead in 2022, he continues to work on picture books. Goryeo Buddhist Paintings, Pictures of Light and Wind, published in 2023, was selected as “an excellent work” in the Sejong Book Liberal Arts category.

Lim Taek-su serves as the Templestay team leader at Baekyangsa Temple in Jangseong. In 2024, he won the Dong-A Ilbo Spring Literary Contest with the short story Long Day, Long Night, and made his literary debut by simultaneously winning the 20th World Literature Award with the full-length novel Kim Seom and Park Hye-ram. He starts every day with a dawn Buddhist ceremony and prayer, and he lives his life forming new relationships every moment at temples.