True Respite, No Better Gift than This

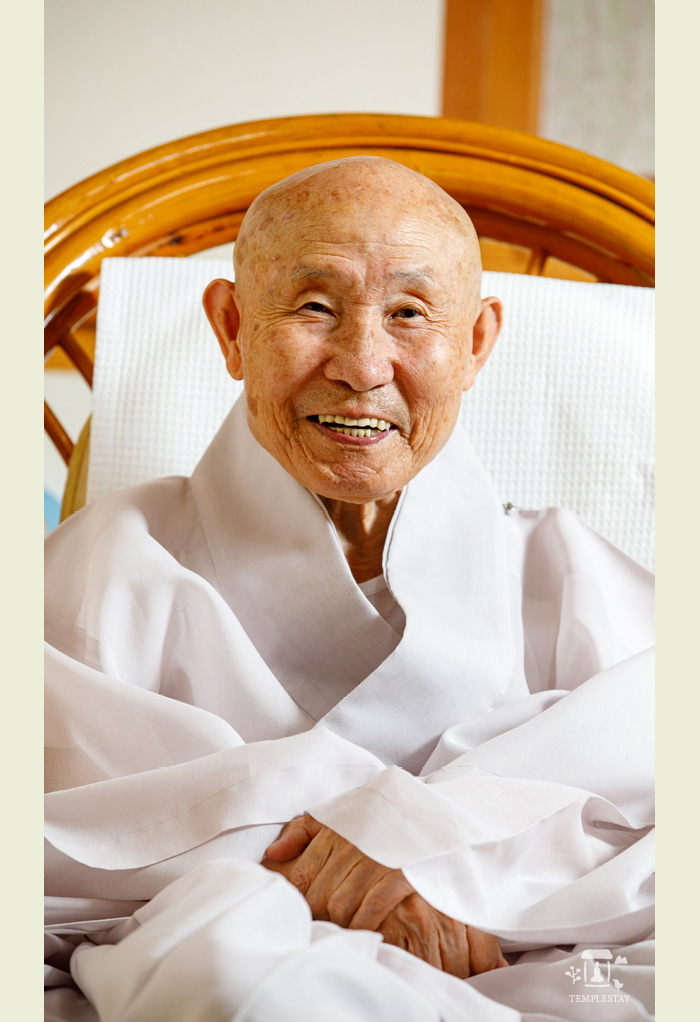

Ven. Muyeo, Guiding Teacher of Chukseosa Temple in Bonghwa

Text by. Baksa Photo by. Ha Ji-kwon

The Chiljeongnye (Ritual of Seven Prostrations) continues for a long, long time. The low, slow chanting in unison shows no sign of ending. When I try to follow along, my chanting becomes thin and soon breaks off due to my limited lung capacity.

But for some reason, when my chanting stops, my earnest heart persists. Could it be the same for those who fill the dharma hall with me? Their long, slow sounds lower to the shiny wooden floor, and my body gradually lowers itself along with the sound. I put my forehead on the cushion in prostration and sense my earnest heart. The communal chanting seems as though it will end soon but does not, and the sun shows no sign of rising.

Even if you don’t know much about Buddhist rituals, if you look at the back of the person in front of you and bow when they do, the ceremony will end before you know it. The chanting usually doesn't last long, so after prostrating a few times, it will be time to leave. Chiljeongnye, the main body of this Buddhist ceremony, is named so because the passage “With utmost sincerity I prostrate” is repeated seven times. When you hear this passage for the seventh time, the ceremony will soon end. Even so, it seems to me that this Chiljeongnye is proceeding slower and slower and will never end.

The dawn Buddhist ceremony at Chukseosa Temple is at 3a.m. and attendance is mandatory. Since Chukseosa Templestay emphasizes “resting, resting, and resting again,” I was surprised to hear I had to attend. Depending on the temple, attending the dawn ceremony is usually optional at most temples to give Templestay participants—who lead busy lives and often don't get adequate sleep—extra time to sleep so they can feel fully rested. However, even though they emphasize “rest” to honor the wishes of Ven. Guiding Teacher Muyeo, they also mandate attendance at the dawn ceremony.

On the way back to my room after the seemingly endless ceremony, I suddenly realized that the “rest” emphasized by Chukseosa Temple may have nothing to do with sleeping in and “becoming one with your bed.” Then, what kind of rest is Ven. Muyeo emphasizing when he says, “Rest thoroughly?” What is true rest? This was the first question I asked Ven.

Muyeo when I had the chance.

The True Meaning of “Rest”

“Actually, defining ‘rest’ is both easy and difficult at the same time. If you truly know how to rest, you are a buddha.” Upon hearing this response, it suddenly seemed that understanding the word “rest” would be more difficult than I thought at this temple.

Ven. Muyeo continues: “Usually, when people say they are resting, they are only practicing the illusion of resting. That is not true rest. They say it is difficult, painful, and hard to rest because they are trying to rest while having all sorts of delusions and worries.”

If so, what is true rest? Ven. Muyeo's answer was concise: “Seon meditation is a way to rest.”

His answer is not something I can relate to right away.

When I think of Seon meditation, the phrases that come to my mind first are: undaunted practice, sitting meditation facing a wall, taking one step further from the top of a 100-foot pole, and the silver mountains and iron wall. Doesn't Seon meditation require hours of enduring numbness in the legs, sitting crosslegged on a cushion and looking up at a picture of an emaciated, fasting Buddha while suppressing one's desires? Isn’t it true that only after going through such a difficult and painful process can you even get close to the buddha realm? However, Ven. Muyeo's interpretation is different. He says, “At the time of the Buddha, many of his disciples attained enlightenment immediately after hearing only a single word uttered by the Buddha. They were people whose minds were truly relaxed in daily life. Those who naturally dwell in a state of rest peacefully even without trying can be called virtuous teachers. Since most people are incapable of that, they inevitably try to find rest by using a hwadu or reciting the names of buddhas.”

Then, how should one rest when they take time out of their busy schedule to come to Chukseosa Temple for one night?

Ven. Muyeo answers, “For one who lives a busy, complicated life in the city, I tell them to sleep well the night they arrive here. It may be hard to rest at first, but once you are well rested, your fundamental way of thinking will change a bit. You can think about and see your own foundation in your own way.

People today are wise and smart, and many of them can see things in a way others don't.”

In that case, a night at a temple would be like the “first level of rest.” Ven. Muyeo explains further, “Temples play a major role in the lives of Buddhists, but to secular people, they were just quiet places in the mountains that didn't have much significance. But Templestay programs opened the door for secular people, opening their eyes as well as ours.”

If we think that everything has a beginning, a night at a temple can be that beginning, not just a night in the mountains. Ven. Muyeo said that one's first step toward practice could begin with the thought, “This is the only way. I must do this. Not doing it will be to my detriment.” If the temple opening its doors to non-Buddhists can lead to this first step, then it can have great significance.

Compassion and Great Indignation toward Oneself

If I spend a night in a temple looking into my heart, what will I see? The first thing I see will probably be anger toward others and self-loathing. In a society so wound up that the expression “state of psychological civil war” is understood by many, it may be difficult to quickly free oneself from the influence of the city—full of conflict and hatred—just by spending a night at a temple.

Blaming others is poisonous to the mind, but shooting arrows at yourself to avoid blaming others is not wise either. The reason “self-compassion”—which is being generous toward oneself—has emerged as an important concept is because of our narrow-minded, cold-hearted society where everyone tends to blame someone else or even themselves. One result is a high suicide rate.

While emphasizing rest, Ven. Muyeo cites three factors very important in Seon meditation: great faith, great indignation, and great doubt. The term “great indignation” or “great anger” weighs on my mind. It is said that anger toward others is poison to the mind, but anger toward oneself for being lazy can be transformed into energy that could lead one to Buddhist practice. If so, is there an interface between great indignation and self-compassion? Ven. Muyeo gives an elaborate answer:

“First, one must arouse faith, then indignation, and then doubt. This is a common approach taught to Seon practitioners. About 700―800 years ago, there was a Seon master named Gaofeng who taught this repeatedly. Indignation is when you criticize and scold yourself harshly, thinking, ‘Why can't I study better? All the great patriarchs and virtuous teachers of the world studied well and attained enlightenment. They became great masters, and great teachers of humanity. What kind of person am I that I can't even properly investigate a single hwadu?’ When you ask yourself these hard questions, you come to your senses and realize you have no choice but to practice harder. Then you gain the determination to study hard and do well.”

“In modern terms, a teacher gently says, as if talking to a child, ‘You have these weaknesses and shortcomings so you really need to study harder.’ This would make one work harder and try harder. This is not like telling you to love yourself and think positively about your weaknesses and shortcomings.”

“In fact, the two approaches are similar in content.

The only difference is the form and expression. The words of Master Gaofeng are from a very high-level perspective to help those who practice Seon after arousing the aspiration to study harder. The latter is general advice to secular society, so it might be more suitable for people today or in the future. These two approaches both have their place.”

Suddenly, I am curious and ask Ven. Muyeo if great indignation helped him in his practice?

He answers, “At first, I didn’t really understand the word ‘indignation.’ I tried to examine it in detail and understand it. I kept thinking about it as if I was memorizing it, and I eventually came to understand it, but it took some time.”

Listening to Ven. Muyeo's humble words, I realized that they are not just about great indignation.

They are also about great faith, great doubt, and encompassed all of the Buddha’s teachings. I was moved because they were the words of a master who had applied them in his life and practice and had come to truly understand them.

Asking about the Mental State where Anger Does not Exist

Then, what is Ven. Muyeo's mental state now? Does he still feel great indignation? It is hard to imagine him getting angry as he always smiles and answers politely and kindly as if talking to a child. Does he also get caught up in the whirlwind of emotions like joy, anger, sorrow, and pleasure? If one practices for a long time, will they no longer experience being swayed by emotions? Ven. Muyeo gives a detailed answer:

“For example when you observe a hwadu and arouse a genuine sense of doubt, and when you maintain a smooth, constant flow of single-minded focus on that hwadu, then your mind becomes so calm and peaceful. As you continue to practice, you enter a state of calm and clarity. When you are in that state, you feel a truly subtle feeling that is difficult to express in words. That feeling is the true happiness you feel from practicing. When you enter that state, all emotional ups and downs disappear.”

“Once you reach that state, anger itself disappears.

In my own experience, the word ‘anger’ disappeared from that day on. That is what practice is. All the unwholesome qualities an ordinary person has disappear in that state, including hate and fits of anger.”

At this point I had to ask him one more question: “Then, do you not get angry at all?” His eyes light up playfully, and he says, “There are two kinds of anger. One originates in hatred, and the other is akin to what a parent feels when children do bad things.

The motivation is different. There are times when you express anger to help people. Sometimes, I act angry.”

Is that what a master is like? He always thinks of ways to help others. Even now, he sets aside time on a certain day every week to meet those who come to Chukseosa Temple to see him. He devotes his time and energy wholeheartedly to listening to many people regardless of their level of practice, occupation, or age to find ways to help them.

No Better Gift than Practice

Before I went to see Ven. Muyeo, another monk I met told me that all the people who had met Ven. Muyeo and listened to him were very satisfied. Many people came to him with various problems, and he gave them the words they needed to hear. They say that the Buddha was a genius who prescribed medicines in accordance with the disease one had. If you continue to follow the Buddha's path, will you become like him in that way too? Ven. Muyeo elaborates:

“Even if you tell the same words to different people, some people will accept them while others will misunderstand them. You have to give people advice suited to their unique situation. Otherwise, it will be of no help. That's why I try to create a turning point for those who come here by using the proper words to help them transform their lives”

“When adults see children fighting and hurting each other, they don't see it as a major issue. They just counsel and admonish them with no sense of attachment.”

"During the time of the Buddha, when he was teaching in different places, it is said that even if he simply passed by a complete stranger and said only a few words, they would immediately become his disciples. With just a few words, they would be edified and converted. Even if such words did not come from the Buddha himself, I think the situation would be similar for those deeply involved in spiritual work or deep in practice.”

The people who come to Chukseosa Temple are diverse, and the answers Ven.

Muyeo gives are also diverse, but what he teaches all of them is proper breathing.

He explains:

“I try to teach the same breathing technique that was taught in the Buddha’s time to everyone who comes here. Even if you can’t practice it consistently, just teaching it has great significance. It’s hard to identify in simple terms the causes and conditions that affect a person. However, if I teach this breathing technique consistently, those who like it will practice it, and if it doesn't work for others, that's the end of it. There's no need to tell people to do Buddhist practice. It is something everyone must do, and absolutely must do.

If you don't do it, you lose out. That’s why I teach this breathing technique to everyone. Whether they do it or not is not my concern. I think there's no greater gift, so I teach it to everyone who comes.”

He then explained the technique in detail, everything from proper posture to proper breathing and their effects. “The Buddha's wisdom is like the sun. The wisdom of ordinary people is like a firefly. Are fireflies any match for the sun? No. When you practice, you will feel the great effect of practice for yourself. If you don't, it's your loss.”

After our interview, I open the door. It's pouring rain. After watching the rain for a while, I feel Ven. Muyeo's parched hand pat me on the back.

Suddenly, I remembered the dawn ceremony we had attended. After everyone had dispersed, I stood at one side of the entrance and watched Ven. Muyeo doing prostrations for a long time. He continued to offer prostrations earnestly and in deep peace as if the Buddha himself was standing in front of him. I couldn't leave the hall while watching him.

As I am lost in thought, I feel Ven. Muyeo's hand pat my back. It seems to be telling me there is a way to escape this world of suffering.

Baksa is a book columnist and famous as a “Buddhism geek.”

She has introduced others to books and culture through various media including broadcasts and daily newspapers, and has interacted with the public through programs including “Book Listening Night” and “Book Listening Evening.” Her Korean publications include: To Me, Travel, and If You Could Smile Even if Your Chicken Had Only One Leg.

Chookseosa Temple

+82-54-672-7579

http://www.chookseosa.org