A Pagoda Enshrining

Buddha's Cremains

Text by. Noh Seung-dae Photo by. Ha Ji-kwon

The pagodas are named Seokgatap and Dabotap

The pagodas are named Seokgatap and DabotapThe Appearance of the Stupa

Most temples have a pagoda or pagodas along with a dharma hall. Devotees usually enter the dharma hall to pay their respects, but historically speaking, the pagoda was established before dharma halls appeared. The pagoda was an object of reverence earlier than buddha statues. Moreover, our Korean stone pagodas often have a longer history than our dharma halls. Dharma halls built from wood have had to be rebuilt repeatedly due to numerous wars, but not stone pagodas. What kind of history do our stone pagodas have?

The etymology of the word “pagoda” is the Sanskrit word “stupa.” This was transliterated into various terms in Chinese, and then into Korean, including the words “soldopa (率都婆), and “joltappa (卒㙮婆).” This was eventually shortened to “tappa (㙮婆),” which then became the current term “tap (pagoda).”

A pagoda made of stone is simply called a “seoktap.”

A stupa is a building that enshrines the cremains (śarīra) of Shakyamuni Buddha. During his lifetime, the Buddha said that a stupa should be built to resemble a round bowl turned upside down, which is why they are called “bokbaltap (覆鉢㙮),” meaning “turned-over bowl stupa.” Initially, the stupa symbolized the Buddha because they enshrined the Buddha's cremains in a world where the Buddha did not exist anymore. Naturally, as faith in Buddhist stupas arose, rituals of paying respects and making offerings also appeared. As a sign of respect for the Buddha, the ritual practice of walking clockwise around a stupa three times—as if circumambulating the Buddha three times—also appeared.

It is often said that China is a country of brick pagodas, Korea has stone pagodas, and Japan has wooden pagodas. This analogy may have arisen as each country chose materials that were easy to find and work with, but it also meant that numerous pagodas were built in these countries.

Stone Pagodas Begin to Appear

Since Korea accepted Buddhism from China during the Three Kingdoms period, wooden and brick pagodas were probably introduced together with Buddhism. In the case of the Baekje Kingdom, there are no existing traces of brick pagodas. Instead, since it accepted Buddhism in the 1st year of King Chimnyu (384), Baekje mainly built wooden pagodas and accumulated much technical know-how about how to build them for about 200 years. Even when the Silla Kingdom built the nine-story wooden pagoda of Hwangnyongsa Temple at the recommendation of Vinaya Master Jajang in the 14th year of Queen Seondeok (645), the chief engineer was Abiji, a Baekje craftsman. Prior to this, Baekje had dispatched three craftsmen to Osaka, Japan, to complete the five-story wooden pagoda of Shinotenji Temple.

Silla built many brick pagodas. However, brick pagodas were not well-suited to the climate of the Korean Peninsula. During the summer rainy season, rainwater seeped inside the brick pagoda, causing a risk of collapse, and during the winter, melted snow water entered the cracks in the bricks, causing them to freeze and crack. Wooden pagodas were vulnerable to fire, and brick pagodas were easily damaged by water and freezing temperatures, so naturally, Koreans eventually settled on granite; it was plentiful and resistant to fire.

The first to build a pagoda out of granite were the Baekje people. Not only stone pagodas but also Buddhist artifacts made of stone were mostly produced by the Baekje people. Rock-carved buddhas, stone lanterns, and stone buddhas also have their origins in the Baekje Kingdom. Evidence of this is found in the Rock-Carved Standing Buddha Triad in Dongmun-ri, Taean (a national treasure), the structural members of a stone lantern at Mireuksa Temple Site in Iksan, and the Stone Seated Buddha in Yeondong-ri, Iksan (a treasure).

The Baekje people carved granite and built pagodas in the shape of wooden pagodas. Since their first models were wooden pagodas, they reproduced these in stone. One example is the Stone Pagoda at Mireuksa Temple Site in Iksan (a national treasure). It was established in the 40th year of the reign of Baekje's King Mu (639), and characteristics found in wooden pagodas can be seen throughout the structure.

Around the time Baekje was building a stone pagoda at Iksan, Silla was building a pagoda in its capital, Seorabeol, using granite cut into the shape of bricks, a style called “mojeon-seoktap.” The Stone Pagoda of Bunhwangsa Temple in Gyeongju (a national treasure) is one outstanding example. This pagoda—believed to have been built in the 3rd year of Queen Seondeok's reign (634) along with the establishment of Bunhwangsa Temple—is recorded to have originally had nine stories, but currently only three stories remain.

The original model for Silla's mojeon-seoktap was of course the brick pagoda. The appearance of the mojeon-seoktap shows that the need for stone pagodas also emerged in Silla. This was because there were many disadvantages to brick pagodas, such as the lack of suitable soil for making bricks and the frequent need for periodic repairs.

The Stone Pagoda of Mireuksa Temple Site.

The Stone Pagoda of Mireuksa Temple Site.

The Stone Pagoda of Bunhwangsa Temple in Gyeongju

The Stone Pagoda of Bunhwangsa Temple in Gyeongju

The East & West Three-Story Stone Pagodas of Gameunsa Temple Site

The East & West Three-Story Stone Pagodas of Gameunsa Temple Site

Seokgatap and Dabotap

Seokgatap and Dabotap

Mireuksa Temple Site in Iksan, where its stone pagoda is located, was originally laid out with three pagodas and three dharma halls, based on the Maitreya Sutra. Its construction was a grandiose state-sponsored project and was possible thanks to the strong government led by King Mu, who ruled Baekje for over 40 years. In addition, there was a great abundance of high-quality granite near Mireuksa Temple, which was a great help. Even today, this place is famous for the production of large quantities of high-quality granite called hwangdeungseok, so named because it is produced in the Hwangdeung region.

However, building such a large stone pagoda in another area would require greater costs as moving large quantities of granite is not easy. Accordingly, a miniature stone pagoda modeled after the Stone Pagoda of Mireuksa Temple Site was built at Sabiseong Castle, now known as the Five-story Stone Pagoda of Jeongnimsa Temple Site in Buyeo (a national treasure).

The four corner pillars of the first story of this pagoda were built using a technique called “minheullim,” which refers to narrowing at the top and widening at the bottom, just like the Stone Pagoda of Mireuksa Temple Site. The thin roof stones have slightly raised ends, imitating the roof line of a wooden building. The Stone Pagoda of Mireuksa Temple Site met its fate here. In 660, the allied Silla-Tang forces captured Sabiseong Castle, took King Uija, the royal family, and some members of the nobility hostage and took them to Tang China, after which the 678-year history of Baekje came to an end. It had been only 21 years since the Stone Pagoda of Mireuksa Temple Site was built.

Seokgatap Pagoda, the Epitome of Elegance

Even during the Unified Silla era, which entered a period of stability after the unification of the three kingdoms, pagoda styles continued to evolve. Silla first produced the mojeon-seoktap pagoda, but found its stability and formative beauty unsatisfactory.

Silla then built stone pagodas by adding wooden pagoda characteristics to the brick pagoda style. One example of this is the Five-story Stone Pagoda in Tamni-ri, Uiseong (a national treasure).

This stone pagoda is 9.6m tall and looks even taller and more imposing as it sits on a hill. The stylobate was made of a single layer in the Baekje style, and the four corner pillars are in the minheullim style.

However, because this stone pagoda was modeled after a brick pagoda, the lower and upper surfaces of the roof stones are terraced like a brick pagoda.

An attempt was made to imitate the roof line of a wooden building by slightly raising the corners of the eaves, but the result was not satisfactory due to structural limitations.

As time passed, craftsmen developed a style of stone pagoda that was an appropriate combination of Baekje's stone pagoda and Silla's brick pagoda.

This is the East & West Three-Story Stone Pagodas of Gameunsa Temple Site (a national treasure). The lower sides of the roof stones imitate the terraced structure of a brick pagoda, while the upper sides follow the roof line of a stone pagoda. These twin pagodas were built in the 2nd year of King Sinmun (682), 14 years after Silla unified the three kingdoms.

They are large pagodas with a height of 13.4m, which reflect the courageous spirit of Silla immediately after unification.

The cultural heyday of Unified Silla was around 750, when Bulguksa Temple and Seokguram Grotto were established. This is when the country became economically and politically stable, its manufactured goods became abundant, and its cultural accomplishments reached their peak. In particular, Bulguksa Temple boasts meticulous composition and spectacular beauty because it was built under an ambitious plan to realize here on Earth the Pure Land where buddhas reside. Naturally, Bulguksa's two pagodas are masterpieces representing Silla's cultural capabilities.

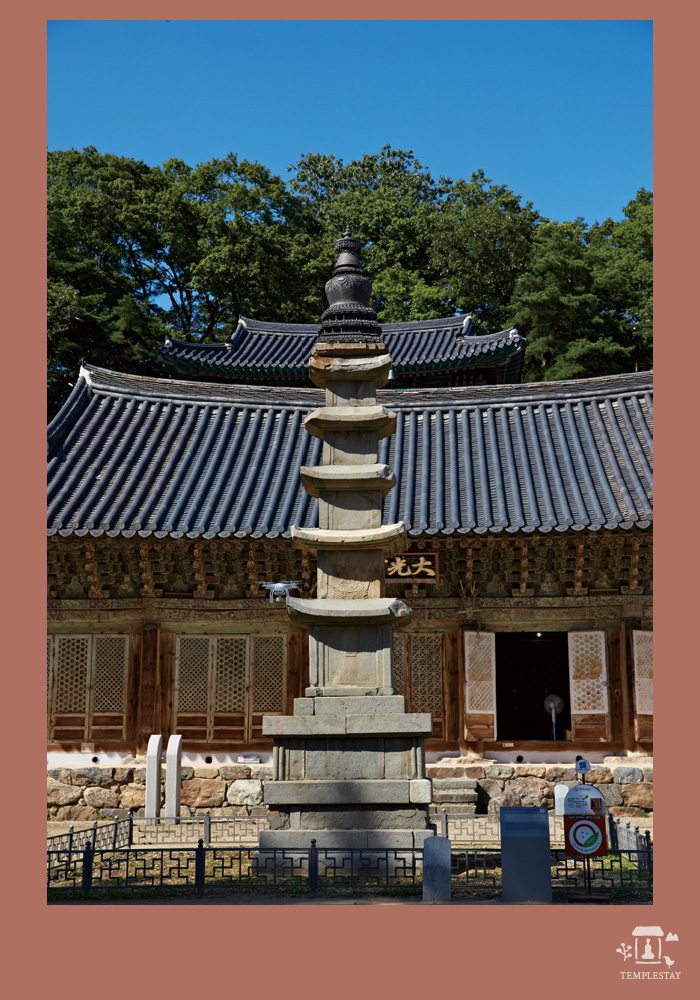

The Five-Story Stone Pagoda of Magoksa Temple

The Five-Story Stone Pagoda of Magoksa Temple

The pagodas are named Seokgatap and Dabotap.

However, they were made in two completely different styles. While Seokgatap has a simple, understated beauty, Dabotap is more splendid with elaborate decorative elements. In the hierarchy of stone pagodas, Seokgatap appears more refined than the twin pagodas at the Gameunsa Temple Site.

With a height of 10.4m, Seokgatap is not a small pagoda, but it still looks elegant. Like the twin pagodas at the Gameunsa Temple Site, Seokgatap's stable posture and balanced beauty stand out, although its bold spirit, like a courageous warrior on a violent battlefield, has been somewhat reduced. Additionally, the body and the roof of each story are each cut from a single stone, giving it a clean, orderly appearance.

Ultimately, Silla craftsmen chose a style that appropriately harmonized wooden pagoda and brick pagoda styles.

Naturally, most of the pagodas built in Silla territory after the establishment of Seokgatap were modeled after it, and three-story stone pagodas with a double stylobate became the basic style of Silla stone pagodas. This indicates that Seokgatap not only had a stable aesthetic but was also easy to construct.

A stone pagoda is a structure usually built in front of a dharma hall, and its size is determined by the height of the dharma hall. The double-stylobate is very important in these cases. In order to match the height of a dharma hall using a single-story stylobate, the stones for the body and roof must be larger. Greater construction costs are also incurred in transporting and trimming stones. However, if you use a double stylobate, the base is wider, making it much more stable, and the size of the body and roof stones can be smaller, making it easier to erect. This is another reason why the Seokgatap style became popular nationwide.

The Multi-Story Brick Pagoda of Silleuksa Temple

The Multi-Story Brick Pagoda of Silleuksa Temple

The Sumano Pagoda of Jeongamsa Temple

The Sumano Pagoda of Jeongamsa Temple

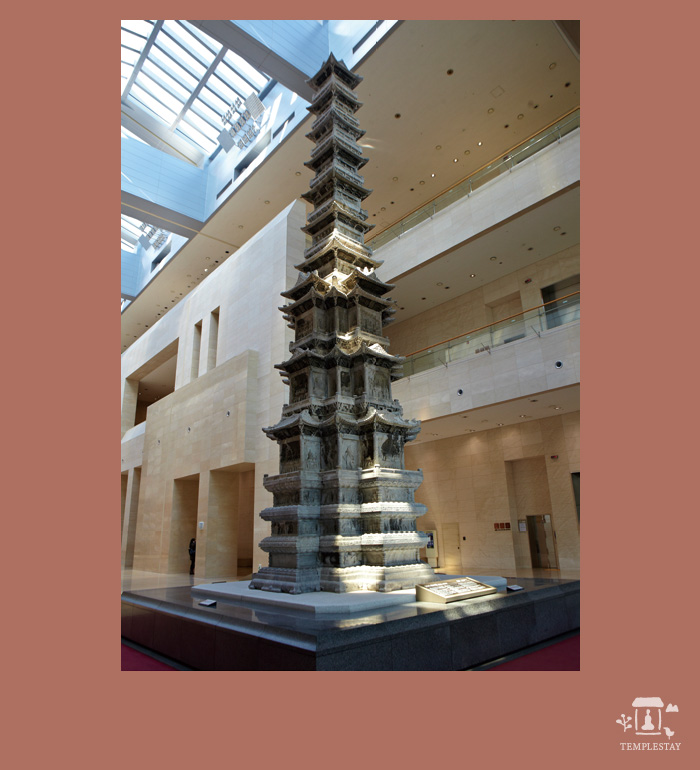

The Ten-Story Stone Pagoda at Gyeongcheonsa Temple Site

The Ten-Story Stone Pagoda at Gyeongcheonsa Temple Site

The Palsangjeon Hall of Beopjusa Temple

The Palsangjeon Hall of Beopjusa Temple

Various Goryeo Stone Pagodas Appear

Since Buddhism was the state religion of Goryeo, which unified the Later Three Kingdoms, stone pagodas were continuously being built. During the Unified Silla period, Seokgatap-style pagodas were built extensively in the old Silla region, but by the Goryeo period, pagodas of various styles were being built throughout the country. If you look at the characteristics of a Goryeo stone pagoda, a support stone is placed under the pagoda's body stone, and the terrace-shaped support stone under the roof stone has a smaller, simpler shape. Overall, the number of stories also increased, and 5-story and 7-story stone pagodas appeared frequently. Hexagonal and octagonal stone pagodas also appeared.

The Five-Story Stone Pagoda of Magoksa Temple (a treasure) is a Tibetan-style stone pagoda from the Goryeo Dynasty. It is topped with a bronze finial in the shape of Tibetan-style gilt-bronze pagodas, a unique style not found in other Korean temples. At the end of the Goryeo Dynasty, craftsmen from Yuan China came in and took the lead in building stone pagodas. One outstanding example of this is the Ten-Story Stone Pagoda at Gyeongcheonsa Temple Site in Gaeseong (a national treasure). After surviving some complicated situations during the Japanese colonial period, it now sits inside the National Museum of Korea.

Goryeo built various types of stone pagodas depending on the political situation, but it also built wooden pagodas, brick pagodas, and mojeon-seoktap which was passed down from the Silla period. One outstanding example of a mojeon-seoktap is the Sumano Pagoda of Jeongamsa Temple in Jeongseon (a national treasure), and one outstanding example of a brick pagoda is the Multi-Story Brick Pagoda of Silleuksa Temple in Yeoju (a treasure). One example of a wooden Korean pagoda was the Five-story Wooden Pagoda of Manboksa Temple in Namwon, built during the reign of King Munjong. However, it was burned down when Namwonseong Castle fell to the Japanese army during Japan's invasion of Korea (1598).

Among the Goryeo stone pagodas, some were built in unique locations not associated with dharma halls.

Stone pagodas were sometimes erected at traditional prayer sites that dated back to before Buddhism's arrival, in order to indicate the sacred nature of the area. Stone pagodas were also erected to compensate for the weak geomantic energy of the mountains and rivers. In short, during the Goryeo Dynasty, stone pagodas for various purposes were built throughout the country.

During the Joseon Dynasty, which established Neo-Confucianism as the ruling ideology, Buddhism was pushed to the periphery, and the construction of stone pagodas, which required a lot of money and manpower, gradually fell into decline. Still, it is fortunate for us to still have the Palsangjeon Hall (a national treasure) of Beopjusa Temple in Boeun, the only wooden pagoda in Korea that was restored after the Japanese invasions of Korea in the 1590s.

Noh Seung-dae has devoted more than 20 years to visiting various sites and studying Korean cultural heritage with an unwavering passion for our culture. The results have been contributed to magazines like Bulkwang and People and Mountains . His Korean publications include Hidden Supporting Actors in Temples and At Temples Goblins Live and So Does Grandmother Samsin.