Free Indeed. What Can Block My Freedom?

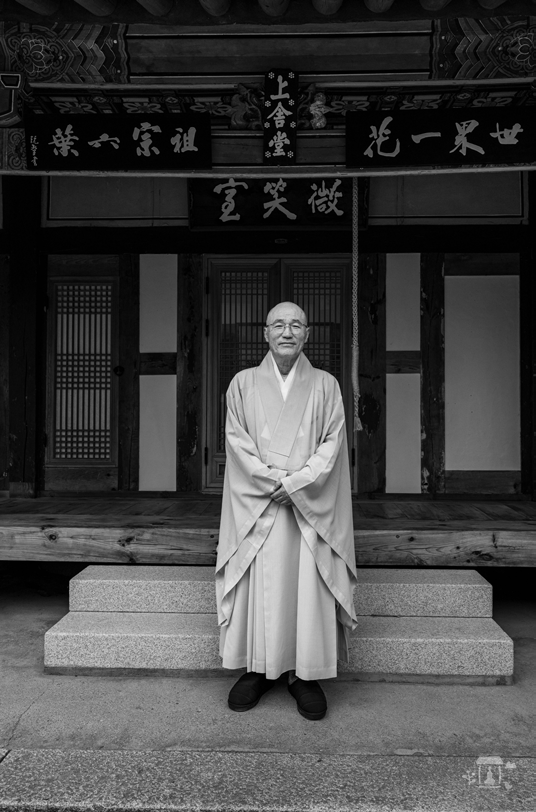

Hyeonmuk Seunim, the 8th Spiritual Patriarch of Songgwangsa Temple, Jogye Chongnim

I used to think that being knocked down and proven wrong was the natural cycle of life. That was before I studied Buddhism. Buddhism taught me that it wasn't me who was being knocked down and proven wrong, but the "concepts" I'd created. All the concepts I held were created by guessing, judging, and deciding what I liked and disliked; I created them as involuntarily as breathing. And every time they were disproven, I thought I was being knocked down and proven wrong. I lived under that delusion for a long time.

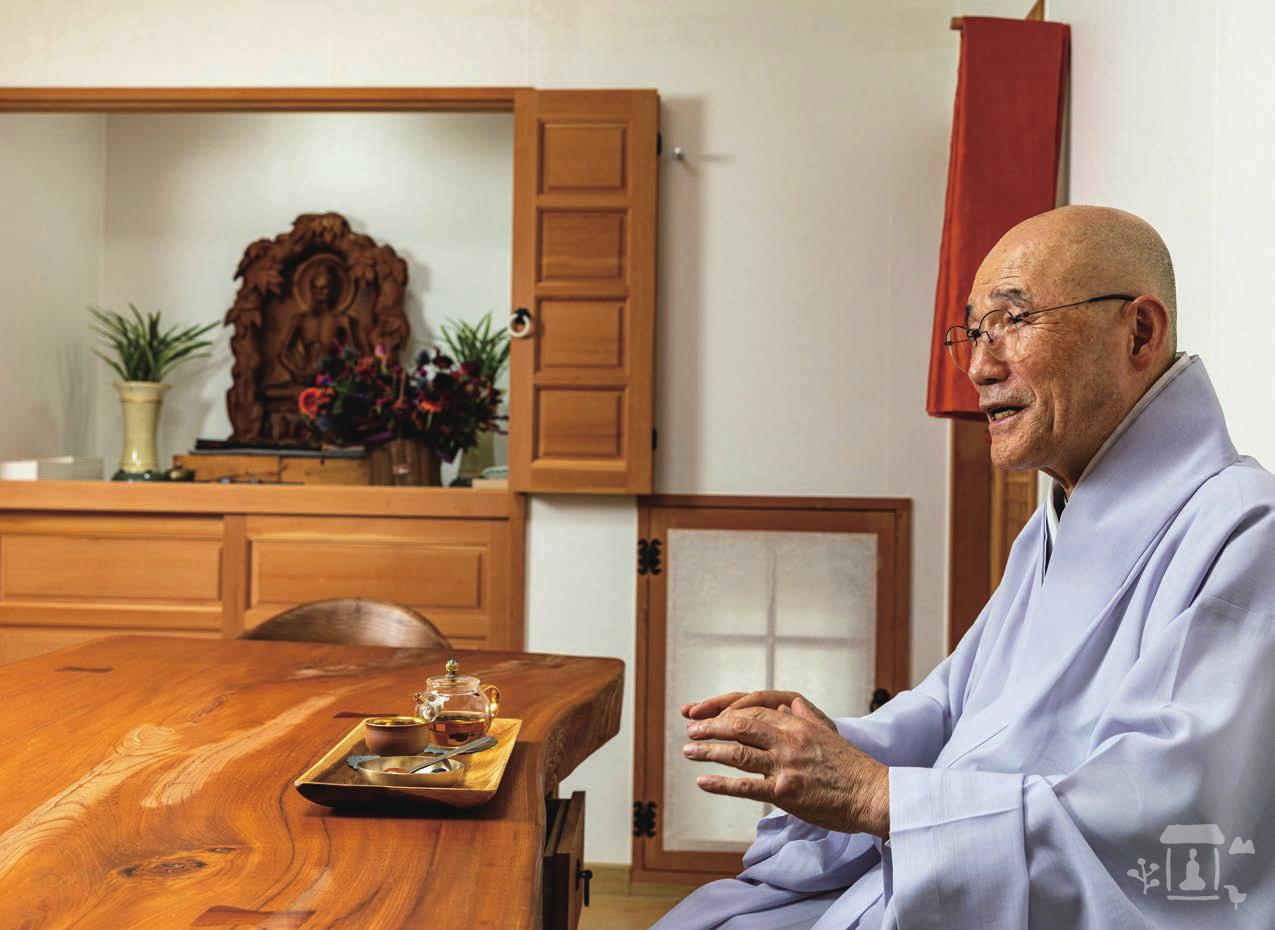

Upon meeting Hyeonmuk Seunim, I was proven wrong three times. First, I had the preconceived notion that he would be strict and fearsome because he held the stern position of "Spiritual Patriarch of the Jogye Chongnim." That was disproven when I saw him rapping cheerfully the Prajna Gatha on YouTube. The second time I was proven wrong was during one of our conversations. I had presumed he would be a free-spirited man, but that was wrong. He had been a man of strict principles and a diligent practitioner since his ordination. The third time I was proven wrong was near the end of another conversation. Our conversation flowed smoothly throughout. I said, "You seem so relaxed and free." He smiled, saying, "Free indeed. What can block my freedom?"

Hyeonmuk Seunim told me two criteria for a person seeking the Way, as described by the Dalai Lama. A person of the Way is, firstly, free from pretense and enjoys inner peace; secondly, they are compassionate. Hyeonmuk Seunim fits these criteria perfectly. All three times I was proven wrong brought me joy and delight.

One of our simple chats began with the autumn scenery of Songgwangsa Temple. No one could deny that Songgwangsa Temple in autumn is truly beautiful. Hyeonmuk Seunim pointed out the beautiful autumn foliage, the bamboo forest paths, and the stone walls, asking us where we had been and where we hadn't. While he encouraged us to take pictures of the beautiful scenery, he disliked posing for pictures. When we reached the stepping stone bridge, a well-known feature at Songgwangsa Temple, he recited a poem by Jeong Cheol that he had read in a middle school textbook.

A shadow appears on the water, and a monk is seen walking on the bridge. Hey monk, pause a minute. I'd like to ask you where you're going. Pointing to the white clouds with his stick, he walks away without looking.

"You Have a Special Connection with Songgwangsa Temple."

Q: About this poem you said, "I must have been destined to become a monk. The poem struck me so deeply that I memorized it immediately. I wrote it down in large calligraphy and stuck it on the wall." How did you come to pursue the path of monastic practice?

A: In my early twenties, I wanted to go to a temple and practice Seon for about a year. I thought it would be helpful in life, even if I didn't become a monk. So, my grandfather went to a man noted for having psychic ability, and told him his third grandson wanted to live in a temple, but he couldn't understand why. The psychic said, "Your grandson had a strong connection to Buddhism in a past life. It is his destiny to wear monastic robes at least once, even if he has to steal it. So, don't hold him back." He then added, "If he goes to a temple, he'll become a great monk."

At a family meeting, my grandfather told everyone: "I was told that our grandson has a strong connection to Buddhism due to a past life, and we should not hold him back."

Everyone agreed. My mother was also the president of the lay Buddhist association at a small rural temple. Jogye Order rules require written consent from a child's parents before that child can join the Order. My parents wrote their consent in calligraphy, and afterward, I visited Gyeongbong Seunim at Tongdosa Temple for the first time.

But Gyeongbong Seunim said, "I'm too old now. I'll introduce you to a good monk. Go see Gusan Seunim at Songgwangsa Temple." But I was from Gyeongsang-do Province, and Jeolla-do Province was unfamiliar to me. So, I went to see Hyanggok Seunim, who was Jinje Seunim's teacher. I paid him my respects and asked him to accept me as his disciple, but he informed me, "These days, my health isn't good, and I hardly take on any disciples. I'll introduce you to a good monk." He then told me to go see Gusan Seunim at Songgwangsa Temple. Only then did I take an interest in Gusan Seunim because two monks had praised him as an outstanding practitioner. And so I came to Songgwangsa Temple. Gusan Seunim asked me, "Did your parents give their consent?" I gave him the consent form and he smiled. Even the monk in charge of academic affairs at Songgwangsa was surprised, saying not many applicants actually bring a consent form.

After living at Songgwangsa Temple for a season, I realized that both Gyeongbong and Hyanggok Seunims were in their eighties and late seventies, respectively. And it wasn't long before both virtuous teachers would pass away. So, I told my teacher, Gusan Seunim, that I wanted to visit and serve other virtuous teachers to broaden my horizons. Later, while studying under Gyeongbong Seunim, I asked him why he hadn't accepted me as his disciple and instead sent me to Songgwangsa Temple. He replied, "Songgwangsa Temple and you have a special connection." He added, "You have a strong resolve and tenacity, so you'll go far."

Afterward, I visited and studied under various teachers and Seon masters, including Gyeongbong, Hyanggok, Jeon- gang, and Songdam Seunims, as well as Seo-am Seunim of Bongamsa Temple, Seo-ong Seunim of Baekyangsa Temple, and Wolsan Seunim of Bulguksa Temple. After doing that for about ten years, I began to feel the urge to settle down in one place. I had a general idea about the path my studies should take by then, and I wanted to try my hand at it.

When I thought about where to go, no place came to mind right away. So, I prayed for 100 days at Gwaneumjeon Hall of Songgwangsa Temple. After that, I went to Cheoneunsa Temple and entered the three-month Seon retreat. As soon as I began Seon practice, the quiet Seon room at Chilbulsa Temple, just across the mountain, kept coming to mind. So, in keeping with my prayer vows, I went there and practiced "noble silence" for seven years. After that, the monks I was living with suggested that we commit ourselves to a three- year retreat, which we all began together.

The Tradition of Raising an Ox

Q: I heard you practiced very intensely. What was it about your mind that enabled you to do so?

A: I didn't practice intensely. I simply practiced Seon faithfully, following the most basic principles. The foundation of those who sincerely seek truth is diligent practice, isn't it?

Every Monday, we clean up the road down there. One time, I went out with a broom and swept, and Hyeon-gak Seunim, who was from the United States, was amazed to see this. At that time, I had the duty of a Yuna, the person in charge of commanding and supervising the entire Chongnim (comprehensive monastic training complex) under the supervision of the Spiritual Patriarch. Hyeon-gak Seunim seemed to be surprised to see me, the Yuna, sweeping. He asked me, "Do you always do this with others?" I told him I did, and he expressed his amazement."

Then I told him, "This isn't something out of the ordinary; it's just fundamental. When the Buddha's community went out on an alms round in the past, he was the first to go out with his alms bowl. He was the first to lead by example. Even my teacher, Gusan Seunim, was always the first to show up with a broom when it was time to clean up, even after becoming the first spiritual patriarch (bangjang) of Songgwangsa Temple. And he would always come with a hoe to help when the community worked in the veggie garden. In a Buddhist community, working together is fundamental to communal life."

Q: I imagine you've had your fair share of difficult times. How did you overcome them?

A: You always have to honor your vows. Difficulties are overcome through vows. When you're not making any progress in your studies, that's when it's truly difficult. It's like rowing a boat on a vast ocean. With no lighthouse in sight and no compass, and the sun beating down on you, you don't know where to go.

In such times, you should go to a buddha hall, pay your respects and vow: "To the Three Venerable Jewels of Buddhism, who express great loving-kindness and great compassion! Please guide me with your compassion. I vow to practice. Please light the lamp of my heart so I may repay the Buddha's great grace and benefit all living beings. Please guide me with your compassion."

You should keep praying like this and push yourself harder. This is called "self-admonition." Bojo Seunim spoke of the "tradition of raising an ox." At first, I thought, "Oh, Bojo Seunim is the oxherd, and we are his oxen. A keen-eyed monk should admonish us and lead us like oxen." That's not correct. It means to think of yourself as an ox and discipline yourself with the same mindset as raising an ox.

Q: You practiced noble silence for seven years. It must have been quite difficult.

A: When I first started, I would talk in my dreams. Then, even in those dreams, I would come to my senses and think, "I vowed to keep silent. But, having spoken, I need to confess that in front of the community. Oh, this is embarrassing..." Then, when I woke up, I thought, "It was only a dream. Thank goodness. I have to be more careful." Still, that went on for six months. After six months, even in my dreams, if someone spoke to me, I would write "noble silence" and not speak. When I don't speak in both reality and in my dreams, I've truly achieved "noble silence."

There was a fellow monk who started with me, and we practiced noble silence for three years. Afterward, one day over a cup of tea, he talked about how, at first, he'd talk in his dreams and admonish himself. But after six months, he quit talking even in his dreams.

Our subconscious mind works so hard because of karma. Dreams are the activity of the subconscious. They say all memories are stored in the subconscious. That's karma. When we try to correct a habit, no matter how much we resolve it at the present consciousness level, its root in the subconscious causes it to rise again. Even with resolutions and commitments, karma continues to reappear.

In Buddhism, the realm of the sixth consciousness is the present consciousness. The subconscious, in Buddhist terms, is the eighth level of alaya consciousness (ālayavijnana) . Below the seventh level of manas consciousness (manasvijñāna) lies the alaya consciousness, where all of our instinctive karma resides. If the root of karma reaches the third level, we must delve deeper and, at the fourth level, we must make a truly fervent vow and resolve to uproot it. However, if we try to resolve it at a higher level, we'll only be eliminating a symptom and not the underlying cause. That's why we relapse. Offering 100 days of prayer allows us to delve deeper into our subconscious. The same goes for hwadu practice in Seon. If we continue to immerse ourselves in it, we can delve deeper into our subconsciousness.

The Only Alternative to Overcoming Mental Afflictions

Q: It must have been difficult to maintain noble silence on your own, and I imagine you must have experienced many inconveniences in communal life with other monks. How did you cope?

A: It was uncomfortable for me, but it must have been uncomfortable for them as well. Some monks would pass by and poke you playfully; others would hide your shoes and go to the meal offering without you. Pranksters do that. They're close dharma friends. You can't get angry. In those times, you need to discipline yourself by perfecting your patience.

You have to reflect on yourself. That's the right thing to do. Even when reading sutras, you need to reflect on yourself to benefit from it. At those times, you can reflect on yourself and think, "I must have tormented and caused trouble to those people in my past life. That's why I'm receiving this karma." Then, instead of holding grudges, you should thank them. Then you'll be able to hang out with them. Practicing noble silence also means that you'll silently endure any insults, without questioning who's right or wrong.

Beopjeong Seunim sent me letters from time to time. He was a very knowledgeable person, and when we spoke, he would often quote scriptures or sayings from ancient patriarchs' records. Listening to them, I learned things. When I sent him newly harvested tea, he would send me a letter hand-written in ink with a calligraphy brush. He once wrote, "When living in a community, it is of great benefit to regard them as your teachers." These words were a truly valuable lesson for me. It's a teaching we all should take to heart in our own lives.

Q: As Songgwangsa's spiritual patriarch, you're the supreme teacher to the monks currently practicing here. And lay Buddhists also come to practice or hear your teachings. Do you speak differently to monastic practitioners and lay Buddhists?

A: There are differences, but the essence is the same. I just explain things more simply to the laity. When I first visited Gusan Seunim and greeted him, he smiled and asked, "What is the most precious thing in this world?" As a monk, I shouldn't be concerned with success or wealth, right? So, I thought about it for a moment and said, "I think peace of mind is the most precious thing." Then, he asked, "What does that mind look like?" I was struck dumb. You have to know your own mind to attain peace. I then wondered how I could desire peace of mind when I don't even know my own mind.

Gusan Seunim then told me that practice is about finding the mind: Only by finding that mind can you truly cultivate peace. That really resonated with me. Indeed, both monastic practitioners and the laity yearn for peace of mind.

Buddhist practice is about finding yourself in the present moment, without thinking about the past or future. It's the same in the military. In the military, if even one person makes a mistake, the entire unit is punished. The thought of being punished made me anxious when I served in the military. I once asked a senior soldier, "What should be a soldier's spirit in those moments of anxiety?" He said the same thing our Seon masters say. Seon masters say: Don't think about what happened a minute ago, don't think about what will happen a minute from now, focus solely on the present moment. And that soldier said the same thing: Don't think about what happened five minutes ago, don't think about what will happen five minutes from now, just focus on what you're doing right now. Don't worry about what comes later. That clear-headed answer resonated deeply with me.

When you have peace of mind, you can maintain your center, unwavering and unswayed. Seon practice is the same. Focus solely on the present moment. That's the wisest approach and the only way to overcome the afflictions of our minds.